Almost a year after the start of the Arab Awakening, the region is in many ways deadlocked. Popular calls for the reform of corrupt and stagnant political systems have fallen prey to the realities of bureaucracy and the difficulties of changing deep-rooted institutions.

In a Q&A, Muhammad Faour looks at the state of education in the Arab world, explaining why true democracy will never take hold if education systems are not reformed to foster citizenship and civic responsibility. Arab countries will only become economically competitive and reliably democratic if they start teaching youth to think critically and respect different points of view.

- How strong is the education system in the Arab world?

- Why is there an urgent need to reform education in the region?

- How are education and democracy related?

- What is education for citizenship?

- How is education reform tied to the Arab Awakening?

- What steps should Arab governments take to improve their education systems?

How strong is the education system in the Arab world?

Most Arab education systems are not preparing students to compete in today’s global, democratic society. Of course, there are substantial variations between Arab countries and within each Arab country (such as differences between urban and rural areas). Some schools in several Arab states offer quality education of international caliber, including Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, and the United Arab Emirates. However, almost all education systems in the Arab world suffer from serious shortcomings, notably with regard to governance and teachers.

Good education requires good governance, but that is lacking in the region at both the central government and the local school level. Ministries of education assume a highly centralized role and continue to be dominated by authoritarian management systems. Furthermore, most ministries lack vision, appropriate strategic planning, efficient supervisory units, and competent human resources. Operating under conditions unfavorable to progress, leaders of any new initiatives will face a host of bureaucratic hurdles, including incompetent officers, many of whom are corrupt, resistant to change, or disinterested.

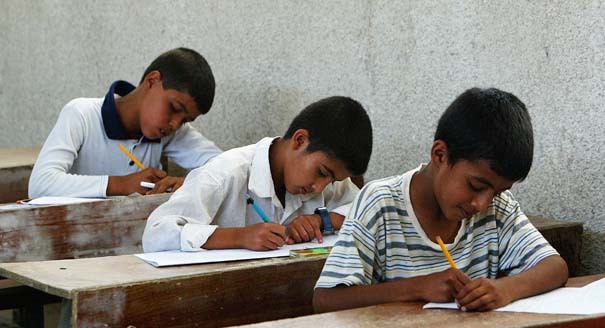

Teaching in most Arab states continues to be highly didactic, teacher-directed, and not conducive to fostering analytical free thinking. On top of that, Arab countries have a shortage of qualified teachers and most of those currently employed have relatively low salaries and limited opportunities for professional development.

Why is there an urgent need to reform education in the region?

Quality education is necessary for economic and social development. Sustainable economic development in the twenty-first century requires certain key competencies for lifelong learning that schools should teach. Skills such as critical thinking, problem solving, digital literacy, and social and civic responsibility are a must for new entrants to the global job market. Most current Arab systems cannot adequately educate students in these vital areas.

What’s more, the Arab world’s burgeoning youth population—one-third of the Arab population is under the age of fifteen—will lead and shape societies and governments in the very near future. Investing in education reform today to encourage responsible citizenship will make all the difference for Arab democracy tomorrow.

How are education and democracy related?

Numerous education programs in democratic countries teach skills and values that are critical to the democratic process and impact students’ intentions and predispositions toward civic and political participation. The best examples of effective systems include Finland, Denmark, and South Korea

These programs encourage such behaviors as social and moral responsibility and personal efficacy and provide students with opportunities to practice civic skills like problem solving, persuasive writing, collaboration, consensus building, and communicating with public officials about issues of concern. In acquiring such knowledge and skills, students become more likely to serve and to improve the communities around them.

What is education for citizenship?

Education for citizenship is at the core of this process of teaching Arab students the skills necessary to thrive in a global, democratic, and competitive environment. The concept encompasses two notions: “education about citizenship” and “education through citizenship.”

Education about citizenship is simply minimal civics lessons that provide knowledge and understanding about history and politics. Education through citizenship gives students hands-on experience with the democratic process, teaching them through involvement in civic activities inside the school, such as voting for the school council, and outside the school, such as joining an environment group in the community.

Education for citizenship covers the aims of both of these approaches; in addition, targeting individual values and inclinations, it is linked with the entire experience of students in schools. These values underpin the most common national goals of citizenship education in many countries: to develop the capacities of the individual and promote equal opportunity and the value of citizenship.

How is education reform tied to the Arab Awakening?

Under authoritarian rule, students were primarily taught to be docile subjects of the state—creative thinking was discouraged and information was treated as indisputable. After all, no dictator wants his subjects to challenge authority.

Now, as some parts of the Arab world—from Egypt and Yemen to Libya and Tunisia—start the long process of democratization, a self-evident but often-ignored fact is that democracy will thrive only in a culture that accepts diversity, respects different points of view, regards truths as relative rather than absolute, and tolerates—even encourages—dissent.

After decades of authoritarian rule, people in the countries experiencing popular uprisings will discover that their societies are not equipped with the skills and values needed to accept different, pluralistic norms of behavior. Making those societies truly democratic requires changes not only to their political structure (electoral law, constitutions, etc.) and leadership, but also serious and sustained changes to their education systems.

Promoting and consolidating democracy is key to the political transformations currently under way; reforming education to foster citizenship is urgently needed if democracy is to take hold in the Arab world.

What steps should Arab governments take to improve their education systems?

The current education reform efforts in the region heavily focus on quantifiable changes, such as building more schools, introducing computers to classrooms, and improving test scores in mathematics and sciences. While necessary and important, this emphasis on the “technical” aspects misses a basic human component. The Arab world needs a comprehensive, whole-system approach that does not ignore or marginalize the citizenship component. Students need to learn at a very early age what it means to be citizens who think freely, and seek and produce knowledge. They must be taught to ask questions and innovate.

Arab classrooms should be transformed to emphasize open discussion and active learning. In this way, students can be taught—not just through formal schooling but, more importantly, through practice—to be well-informed, independent-minded members of society. This method has been shown to be far more effective than the lecture-based approach prevalent across the Arab world. Its effectiveness was confirmed in the International Civic and Citizenship Education Study (ICCS) of 2009, which found that the classroom climate most conducive to high levels of civic knowledge is characterized by an openness to discussion of political and social issues.

Thus, training and keeping highly qualified teachers—particularly those able to foster debate and see issues from multiple points of view—is imperative. And by the twelfth grade, a student should be able to solve problems, write persuasively, collaborate, build consensus, and communicate with elected officials.

Perhaps the biggest challenge facing the implementation of such education reform is not one of technical nature but more of political will. The future of Arab society depends on overcoming that challenge.