Alexander Gabuev

{

"authors": [

"Alexander Gabuev"

],

"type": "commentary",

"centerAffiliationAll": "",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"Carnegie China",

"Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center"

],

"collections": [],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"programAffiliation": "",

"programs": [],

"projects": [

"Eurasia in Transition"

],

"regions": [],

"topics": [

"Economy"

]

}

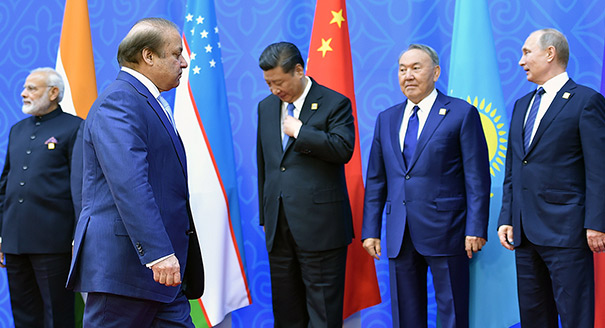

Source: Getty

Bigger, Not Better: Russia Makes the SCO a Useless Club

The Kremlin is still anxious about the expansion of Chinese influence in Central Asia, which is why it has turned the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, set up in order to work out widely accepted rules of the game for Eurasia, into a useless bureaucracy. Now, Beijing can develop relations with other SCO members without worrying about what Moscow thinks.

The Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) formally announced its expansion in June, turning from a six-member organization into a club of eight with the addition of India and Pakistan as members. “The addition of new members will give a powerful new impetus to the organization’s development and will promote the growth of its international authority,” declared the host of the summit in Astana, Kazakh President Nursultan Nazarbayev.

But does bigger really mean better? Some expect that enlargement will turn the SCO into a more ceremonial and less viable organization.

Russia is happiest about SCO expansion. Presidential aide Yuri Ushakov noted that with the addition of India and Pakistan, the SCO now accounts for about 23 percent of the planet’s landmass, 45 percent of its population, and 25 percent of global GDP.

But expanded size may not mean expanded influence. There exist bigger organizations in Eurasia, such as the Asia-Europe Meeting (AEM), which represents even more land, people, and GDP dollars. The AEM also holds regular summits, attended by the leaders of 51 states (representing 60 percent of the globe’s GDP), but with little demonstrable impact on the world.

The SCO was founded in 2001 as a platform where Beijing and Moscow could jointly develop rules of the game for Central Asia and then gently impose their collective will on the region’s nation-states. After an initial focus on settling border disputes in the region, the organization developed an agenda based on security, economic development, and humanitarian cooperation.

For China, this was an entrée into the post-Soviet space, as other existing institutions—such as the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO) military alliance and the struggling Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS)—were still centered on Russia. Central Asia was important for China first of all because of the unstable situation in its Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, bordering Central Asia and populated by ethnic Turkic kin of Central Asians. Beijing was also worried about the conflict in Afghanistan and the deployment of U.S. military infrastructure in Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan after the beginning of the Afghan campaign in 2001.

China had also become a net importer of hydrocarbons in 1994, and wanted to secure overland oil and gas transportation routes across Central Asia. In the longer term, China was interested in Central Asia as an export market for its goods.

Given Russia’s historical dominance of Central Asia, Beijing could not achieve its objectives without having Moscow on board. In private conversations, Chinese officials and experts said that the project was seen as China’s first experiment in creating an institutional “condominium” in a specific region in partnership with another major power.

The interests of Russia and China in Central Asia largely aligned on issues such as keeping local authoritarian regimes in power and fighting the “three evils” of separatism, extremism, and terrorism. In the 2000s, Moscow was not opposed to building oil and gas pipelines from Central Asia to China, as these would reduce the motivation for the region’s countries to seek routes to Europe bypassing Russia.

The SCO largely succeeded as an instrument for coordinating the security interests of China and Russia in Central Asia. The SCO’s Regional Anti-Terrorist Structure (RATS) was instituted in Tashkent. Although SCO officials often joke that the special service officers assigned to RATS spend more time spying on each other than jointly fighting terrorism, it has been welcomed by all sides. The “Peace Mission” joint military exercises, six of which have been held since 2005, are even more valuable.

However, China did not achieve its economic objectives. From 2010, Beijing pushed for both the establishment of an SCO development bank and an SCO free trade zone. Almost all of the SCO member countries were uneasy about the idea of a trade zone. If they got rid of customs barriers, they risked letting the Chinese economic behemoth steamroll over many sectors of their economies.

Most SCO members were more enthusiastic about a regional development bank. After the 2007–2009 financial crisis, many of the member countries desperately needed cash, and here was wealthy China offering to provide favorable loans through a multilateral mechanism. At the height of the crisis, then Chinese leader Hu Jintao publicly promised that China would offer SCO members up to $10 billion in favorable loans.

However, Moscow opposed the idea of a regional bank.

As far as Russia was concerned, the Chinese were excellent partners when it came to pushing the Americans out of Kyrgyzstan’s Manas air base; supporting then Uzbek president Islam Karimov, who had drowned the Andijan protests in blood in 2005; and practicing repelling “color revolutions” through joint training exercises.

However, Moscow was alarmed by Beijing’s economic agenda for the SCO. Well aware of the disparity in economic potential between the two countries, the Kremlin decided to torpedo the establishment of an SCO development bank and free trade zone.

A free trade zone was never popular given the protectionist sentiments of other SCO members. As for the bank, Moscow put forward conditions that it knew Beijing could not accept: it asked China to join the Eurasian Development Bank, headquartered in Almaty, in which Russia controlled 65.97 percent of stock and Kazakhstan—about 32.99 percent. This was unacceptable for Beijing. It wanted charter capital contributions to be proportional to GDP, which would have granted China more than 80 percent of stock. The project never materialized.

Russia wasn’t content with merely blocking the SCO’s economic agenda. Since 2011, Moscow has been pushing for expansion of the SCO by way of inviting India, a country with which it has had traditionally friendly relations. Moscow argued that Russia, China, and India were already working trilaterally, and that this innovation would only increase the clout of the SCO.

China fought back against this idea for a while, as the admission of India did not fit with its plans for a Sino-Russian condominium for Central Asia. It began to change its position in 2013 for three reasons.

First of all, Beijing realized that Moscow would not accept the creation of an SCO development bank and free trade zone on terms China found reasonable. At the same time, China came to understand that it did not really need the bank in order to promote its economic interests in Central Asia. After the financial crisis, the countries of the region lined up to take Chinese money, and Beijing began offering credits on a bilateral basis through its state banks. By lending to individual countries, Beijing avoided multilateral regulations and could therefore take full advantage of the borrowers’ difficult position and obtain very lucrative terms.

Russia was excluded from this scheme and could do nothing to stop it. By that point many Russian state-owned companies such as Rosneft were themselves on the hunt for Chinese loans, and Moscow did not have the spare funds to compete with Beijing.

Secondly, in 2013 President Xi Jinping presented the idea of the “Silk Road Economic Belt” (SREB) at the Nazarbayev University in Astana. The idea grew into the monumental One Belt, One Road initiative. It allowed China to develop relations with any country that had expressed interest in the SREB, without worrying about other countries. By May 2015, Beijing had signed agreements on partnering the SREB with national infrastructure development programs in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan. On May 8, this process culminated in a declaration signed by Vladimir Putin and Xi Jinping on coordination between the SREB and EurAsEC.

The boundless Silk Road initiative, bolstered by China’s financial potency, turned out to be much more useful for promoting Beijing’s geo-economic interests than the institutionally defined SCO, in which all decisions were made strictly by consensus.

Finally, in 2014 China began experimenting with establishing universal financial institutions that could supplement or replace key entities of the Bretton Woods system, such as the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank. These new banks satisfied Beijing’s need for platforms where Chinese financiers could practice setting up China-centric global institutions and obviated the need for an SCO development bank.

After weighing all of these factors, China agreed to admit India to the SCO on the condition that Pakistan—China’s main partner in Southeast Asia—would be able to join at the same time. Chinese diplomats and experts say that Beijing was fully aware that the long-standing antagonism between New Delhi and Islamabad might completely paralyze an organization that was already fairly inefficient due to its members’ constant “special opinions” on various issues.

As the SREB and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) developed, China had stopped seeing the SCO as a useful instrument. Having a major organization with its headquarters in Beijing and “Shanghai” in its name was symbolic reward enough for the possible transformation of a once-useful platform into a useless club.

The SCO’s expansion is unlikely to be matched by greater institutional power, chiefly because the India-Pakistan relationship is unlikely to improve in the foreseeable future. For example, no one could even imagine New Delhi and Pakistan sharing intelligence information on terrorist organizations.

The overall strategic landscape is changing rapidly for Eurasia’s great powers. Carnegie India Director C. Raja Mohan noted that New Delhi had first pursued SCO membership in a completely different global environment, when it seemed that developing dialogue with Beijing and Moscow was the only way to strengthen its position in Eurasia. But now, China is increasingly becoming India’s strategic adversary, while India’s relations with the United States are improving.

Russia has learned an important lesson from this situation. Because the Kremlin had not completely overcome its phobias about the rise of China and its growing influence in Russia’s traditional zone of interest, Central Asia, Moscow has turned a multilateral organization established to develop rules of the game for Eurasia into a useless bureaucracy.

Now, the enervated SCO no longer has any sway over Beijing. The Chinese dragon is no longer bound by any institutional obligations, and it can develop relations with other SOC members without worrying about what Moscow thinks. One good example of this was the establishment of a four-party mechanism for consultations on security matters, which includes China, Tajikistan, Afghanistan, and Pakistan—an arrangement would very likely have been formerly created within the framework of the SCO.

Russia could have tried another tack. If, instead of wasting the energy of its diplomats and other negotiators on blocking the idea of an SCO development bank with a majority stake for China, Moscow had put that effort into preparing normative documents for a Eurasian bank analogous to the World Bank or AIIB, it would have served Russia’s national interests much better.

Moscow decided at the time that this was not acceptable—that if it ceded control to China, then no amount of normative documents could prevent Beijing from pushing its national interests via the bank. Yet the example of AIIB attests to the contrary. As soon as countries such as Germany, Great Britain, and Australia became involved in founding the bank, Beijing quickly gave up the model of creating an international version of a Chinese state bank. It committed itself instead to building a truly global institution that follows transparent rules of the game, even if it held a majority stake.

Moscow evidently wants to limit Chinese expansion into Eurasia by wrapping up Beijing’s initiatives (such as One Belt, One Road) within even larger-scale projects such as a “Greater Eurasia” partnership stretching from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean. President Vladimir Putin again mentioned this project at the SCO summit in Astana. But to pursue a more effective strategy in Central Asia vis-a-vis China, Russia should try to learn from its past mistakes.

About the Author

Director, Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center

Alexander Gabuev is director of the Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center. Gabuev’s research is focused on Russian foreign policy with particular focus on the impact of the war in Ukraine and the Sino-Russia relationship. Since joining Carnegie in 2015, Gabuev has contributed commentary and analysis to a wide range of publications, including the Financial Times, the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, and the Economist.

- With Putin in Charge, Russia’s Vassalage to China Will Only DeepenCommentary

- BRICS Expansion and the Future of World Order: Perspectives from Member States, Partners, and AspirantsResearch

- +16

Stewart Patrick, Erica Hogan, Oliver Stuenkel, …

Recent Work

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

More Work from Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

- Getting Debt Sustainability Analysis Right: Eight Reforms for the Framework for Low-Income CountriesPaper

The pace of change in the global economy suggests that the IMF and World Bank could be ambitious as they review their debt sustainability framework.

C. Randall Henning

- How Middle Powers Are Responding to Trump’s Tariff ShiftsCommentary

Despite considerable challenges, the CPTPP countries and the EU recognize the need for collective action.

Barbara Weisel

- How Europe Can Survive the AI Labor TransitionCommentary

Integrating AI into the workplace will increase job insecurity, fundamentally reshaping labor markets. To anticipate and manage this transition, the EU must build public trust, provide training infrastructures, and establish social protections.

Amanda Coakley

- The EU’s New Industrial Strategy and Global DisorderResearch

The fear that Europe might ‘fall behind’ rival economic powers has long shaped European integration. In the present phase of global disorder, this fear has intensified.

Scott Lavery

- Does Russia Have Enough Soldiers to Keep Waging War Against Ukraine?Commentary

The Russian army is not currently struggling to recruit new contract soldiers, though the number of people willing to go to war for money is dwindling.

Dmitry Kuznets