In recent months “neijuan” (内卷), or “involution,” has become one of the most important buzzwords in Chinese policymaking circles. It has come to describe a disruptive process of relentless competition and price cutting among Chinese businesses, and has been increasingly criticized by policymakers, from President Xi Jinping down, for leading to a zero-sum race to the bottom, marked by vicious price wars, large-scale losses, homogenous products, and improper business practices. An August 2 article in Caixin explains:

China’s top economic planner vowed on Friday to intensify its crackdown on “involution,” pledging to curb disorderly corporate competition, rein in wasteful investment and standardize local governments’ business attraction practices to protect fair market order.

The article is referring to the July 30 Politburo meeting that set out Beijing’s priorities for the second half of 2025. Of the three main priorities, two—the need to boost domestic consumption and the promise to support the real estate market—have been proposed regularly in the past three to four years. Much of the focus, however, was on the newest priority, which is to battle deflationary pressures by reducing “disorderly” price competition and overcapacity in manufacturing—measures, in other words, aimed at reining in involution.

But while Beijing’s new emphasis on ending involution reflects real and pressing problems in the Chinese economy, involution does not represent anything truly new. It is mostly a concentrated version of China’s persistent and structural problem of excess capacity, driven by the economy’s inability to align increases in domestic production with increases in domestic demand. It is a problem already reflected in one of the other priorities of the July 30 Politburo meeting—the need to boost domestic consumption. All three priorities are, in turn, designed to address distortions in an economic model in which implicit and explicit transfers from households have long subsidized growth in investment and manufacturing capacity.

And as long as Beijing’s growth strategy prioritizes growth in production, even when that growth comes at the expense of domestic demand, the underlying pressures that lead to involution cannot be resolved. They can be addressed within specific sectors of the economy, but only by shifting excess capacity to other sectors. That is why, in the end, I expect “involution” will join the list of earlier words and phrases—like “rebalancing,” “dual circulation,” “supply-side structural reform,” “deleveraging,” and “excess capacity”—that had emerged in the past to express the same set of problems, and whose sudden surge in usage often faded away.

Excess capacity and the property bubble

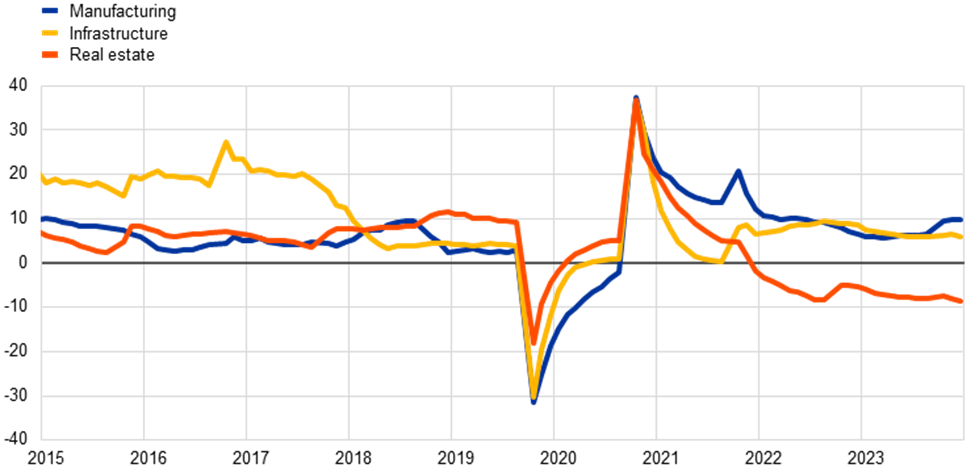

The roots of involution lie in China’s decades-old growth model, but its most recent manifestation emerged in the few years since the end of China’s property bubble in 2021-22. The graph below lists the annual growth rate of fixed asset investment in China by sector. As it shows, before 2021-22 the growth rate of investment in real estate and infrastructure exceeded the growth in manufacturing investment, often substantially.

Source: Alexander Al-Haschimi and Tajda Spital, “The evolution of China's growth model: challenges and long-term growth prospects,” ECB Economic Bulletin, Issue 5/2024, May 20, 2024, https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/economic-bulletin/articles/2024/html/ecb.ebart202405_01~a6318ef569.en.html.

Beginning in 2021-22, however, China suffered a substantial drop in real-estate investment as property developers rushed to cut back on no-longer-viable projects. But with growth in investment driving a disproportionately high share of GDP growth for decades, it was clear that a drop in overall investment growth would force a drop in GDP growth.

In order to prevent this from happening, Beijing was forced to balance the rapid decline in real-estate investment with a commensurate rise in investment in some other sector of the economy. One possibility was to expand infrastructure investment, but perhaps because extraordinarily high levels of infrastructure investment in the previous decades made policymakers increasingly worried about misallocated infrastructure investment, Beijing did not fully commit to this path the way it had after the 2007-08 global crisis.

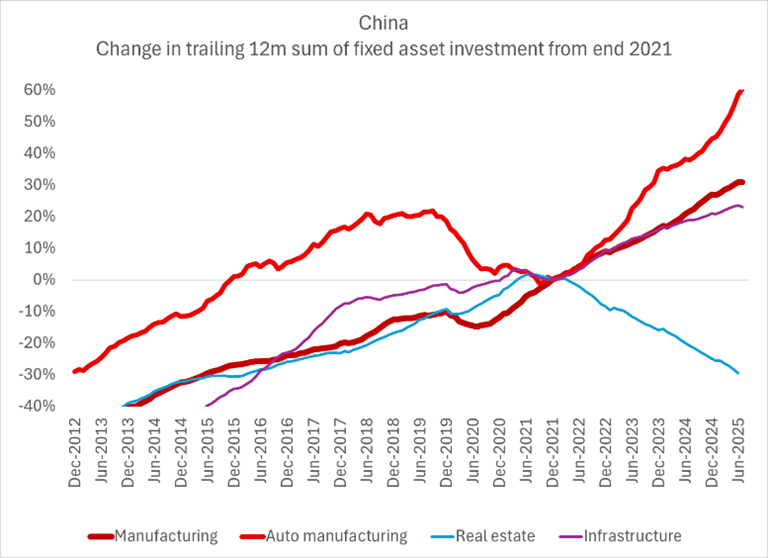

Growth in infrastructure investment did pick up, but not by enough to make up for the decline in property investment. Instead, Beijing chose to engineer a much larger shift in investment flows from property to manufacturing. This can be seen in the graph below.

Source: Brad Setser (@Brad_Setser), “A chart that illustrates the point that @michaelxpettis is making -- and that highlights the dilemma Chinese policy makers face.,” X, August 24, 2025, https://x.com/Brad_Setser/status/1959401335134052555/photo/1.

It is important to note that the acceleration in manufacturing investment was not planned around any expected acceleration in Chinese or global demand. It was determined mainly by the need to keep investment growth from dropping. And while it affected nearly all domestic manufacturing sectors, it did so unevenly, with increases in investment driven largely by domestic political imperatives. Those industries that Beijing had identified as “strategic,” and which local governments were eager to be seen supporting, benefitted disproportionately.

This meant that a notable share of the increase in manufacturing investment was directed to the production of solar panels, electric vehicles, and batteries—industries that had been identified by Beijing as the “new three” industries that would lead China’s future growth. It was the combination of a surge in manufacturing investment and the unevenness of its distribution that ultimately determined the contours of “involution.”

The result was perhaps predictable. Manufacturing capacity grew in most sectors, but “strategic” industries—already producing more than could easily be absorbed by Chinese and foreign demand—saw their capacity multiply.

The solar panel industry

Polysilicon production for solar panels became a posterchild for this process. Before the property collapse, polysilicon and solar panel producers were already manufacturing more than the world could reasonably absorb, but after 2021-22, production capacity soared. In less than four years, the top four Chinese manufacturers alone added about two-thirds of the industry’s existing capacity globally, with Chinese producers eventually accounting for roughly 95 percent of global supply—roughly twice global demand.

Capacity utilization quickly fell. In 2024, capacity utilization had already dropped to below 60 percent. In the first half of 2025, China added 212 gigawatts of new solar capacity, more than double the amount they added in the first half of 2024. Capacity utilization in 2025 dropped to below 40 percent.

The consequences were foreseeable. As Chinese capacity in these industries skyrocketed, inventories spiked. Because rising inventory had to be financed by an increasingly reluctant banking system, or by local governments already struggling to manage excessively high debt levels, this put enormous pressure to clear inventory.

And they tried. By late 2024 and early 2025, solar panels were selling not just below average costs, but, in many cases, producers were forced to sell them below variable costs. As losses mounted, rather than reduce excess capacity, local governments continued to support local producers. This drove them to try to manage losses, and one of the ways to do that is by reducing labor costs. Last year, for example, major producers not only cut wages, but also laid off nearly a third of their workforce. The sector was a money-losing machine.

Ending involution in the solar panel industry

The trendsetter in creating involution became the trendsetter in resolving it. Just as the polysilicon industry was one of the worst affected by involution, it has also been at the forefront of attempts to resolve it. Regulators and producers were already struggling to manage rapidly worsening conditions at the time of the July Politburo meeting. On August 1, Reuters published an article detailing the result of their work:

Chinese producers of polysilicon, a building block for solar panels, are in talks to create a 50 billion yuan fund to acquire and shut down roughly a third of production capacity and restructure part of the loss-making sector. The top polysilicon producer told Reuters on Thursday plans were being discussed to acquire and shut at least 1 million metric tons of lower-quality polysilicon capacity.

To stabilize the industry, in other words, producers and regulators planned to create a RMB 50 billion fund whose purpose is to acquire and shut down about a third of capacity. This should of course relieve selling pressure and reduce the rise in inventories.

The market’s first reaction seemed to suggest that this was just what China needed. The announcement sharply boosted stock prices for solar-panel producers and caused polysilicon prices to rise by nearly 70 percent in July. With discussions ongoing, an August 20 article in Yicai noted that “Chinese regulators, including the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology, have arranged another round of meetings with photovoltaic companies, aimed at reversing persistent unhealthy competition that has eroded profits.”

Consolidation in the polysilicon industry may set the framework for future discussions about involution in other sectors. In that case we should expect to see more such meetings and announcements over the rest of 2025, as regulators take administrative measures to try to reduce excessive price competition in the industries suffering most from involution.

Is involution an administrative problem?

But will administrative measures to limit price competition and cut capacity effectively address the underlying problem? Here, I think, it pays to be very skeptical. Systemic problems require systemic solutions, but these seem like incremental solutions for parts of the system.

Cutting capacity in selected areas will almost certainly reduce involution in those sectors, but it doesn’t address the original problem created by the sharp fall in property investment. If China cuts investment in the worst-hit areas, total investment growth in China will decline, and this will feed directly into a decline in GDP growth and a rise in unemployment.

But if Beijing wants to avoid a slowdown in GDP, and because China has been unable to close the gap between growth in production and growth in consumption, any contraction in investment in the worst-affected sectors must be matched with an expansion in investment in other sectors. If it isn’t, China faces the same problem it faced after the 2021-22 decline in property investment.

Involution, in other words, was not an accidental or idiosyncratic feature of a few industries. It was the result of a growth model that could not permit a decline in investment growth. It is a growth model, in other words, designed to lead not just to rapid technological advancement, which it certainly has, but also to generalized excess capacity.1

Sectors suffering from involution did not cut prices out of malice or error, but because they were producing more than they could sell, both at home and abroad, and could not afford the resulting rise in unsold inventories. The fact that the worst forms of involution occurred in those manufacturing sectors most favored by the government suggests that it is a systemic problem driven by political imperatives.

In that case, as long as political imperatives push local governments and SOEs to expand production, even when this means constraining household income growth relative to output growth, there will be more supply than demand. Beijing can shift this imbalance across sectors—from property to manufacturing, from low-tech to high-tech, and so on—but it cannot make it disappear without a more fundamental adjustment in the structure of its economy.

In that context it is worth noting a recent announcement by the People’s Bank of China on its plans to increase support for “key sectors.” According to an article in Yicai:

China will focus on optimizing fund allocation while keeping overall financial growth on track and directing more resources to key areas such as science and technology innovation and advanced manufacturing, the People’s Bank of China said in its monetary policy implementation report for the second quarter.

Meanwhile, according to an article in last week’s Reuters, “a key segment of China's petrochemical sector is set to expand by almost half between now and 2028, even as growing competition in the broader refining sector slashes profits.” Refiners have been piling into petrochemical products in China’s overbuilt refining sector in defiance of a squeeze on profits, prompting Fu Xiangsheng, vice chairman of the China Petroleum and Chemical Industry Federation, to complain that this sector, too, is facing “involution.” Even as Beijing tries to reduce involution in the worst-affected sectors, in other words, the system is still geared toward supporting production capacity to meet GDP growth targets.

Structural economic changes

In an article published in the Financial Times in October 2024, Martin Wolf, after pointing out the relationship between the end of China’s property boom and the subsequent surge in manufacturing investment, noted that “an economy whose potential growth rate is 5 per cent at most will not invest more than 40 per cent of GDP productively.” If it persists, he added, “it is sure to lead to waste and yet bigger mountains of bad debt.”

Involution is just one of the ways in which this “waste” can be manifested. And if the problem is systemic, rather than specific to a few isolated and idiosyncratic sectors, there are only two ways to resolve overcapacity at the systemic level:

- Increase demand faster than growth in industrial capacity. This requires boosting household consumption, which in turn requires implicit or explicit income and wealth transfers—either from the central and local governments, or from businesses and manufacturers—to the household sector. But this has proven difficult.

- Cut capacity to bring it line with domestic demand. In the short term this means closing factories, laying off workers, and accepting slower growth. But this clashes with Beijing’s determination to maintain employment stability and meet GDP growth targets.

For now, Beijing has chosen to patch up the system with administrative measures, shifting excesses from one sector to another, and relying on exports to cushion the imbalance. But this is a stopgap solution that “works” only by shifting excess capacity across different sectors in the economy. Capacity was cut in the property sector, but it had to shift to advanced manufacturing sectors. It may be cut in polysilicon, but local governments will respond by building more infrastructure or by subsidizing expansion in some other manufacturing sector. Price wars may be suppressed in EVs, but they will flare up in batteries, ships, steel, or petrochemicals.

Over the longer term—unless the rest of the world is able to absorb a permanent expansion in Chinese production relative to Chinese demand (via a growing Chinese trade surplus)—the current system is unsustainable, but over the short and medium term it can continue as long as the Chinese financial system is able to fund increasing amounts of non-viable economic activity. As we’ve seen in the many historical precedents throughout the twentieth century, it is the rising debt burden that sets the limit.

Until then, the most likely outcomes are some combination of:

- Large trade surpluses, as external markets share the burden of China’s domestic imbalances.

- Growing inventories, as unsold goods accumulate.

- More deflationary pressure, either as businesses compete directly on prices or as losses are subsidized by further household transfers, most likely in the form of low interest rates and downward pressure on wages.

- Rising debt levels, as banks are forced to continue funding excess capacity in manufacturing and infrastructure.

None of these are new, which is why Beijing’s new war on involution is really the same as the old war on earlier manifestations of these structural imbalances. As long as China cannot grow consumption much faster than production, involution will persist in one form or another.2 It will just have a different name.

Notes

1It has become very common in the debate over China’s economic future to counter a standard bull case for the Chinese economy with a standard bear case. The bull case consists of China’s unquestionable and seemingly unstoppable technological advancement (along with, in the less sophisticated version of this argument, its growing trade surpluses). The bear case is the exhaustion of Chinese growth as increasingly non-productive investment leads to excess capacity, unsustainable increases in debt, and global trade conflict.

What is missed in this debate is that these are not two opposing conditions. Instead, both can be true, with the former simply one of the ways in which the latter is manifested. After all, if one of the areas of overspending is advanced technology, it would not be surprising if technological advancement were both rapid and, ultimately, unsustainable. We saw similar debates about the USSR in the 1960s and Japan in the 1980s, when the argument that their rapid growth was unsustainable was countered by claims that their very advanced technology was developing at a rapid pace. But when rapid technological advancement is itself one of the consequences of systemic overinvestment, the former cannot be proposed as evidence that the latter is not also correct.

2The extent by which consumption growth must exceed GDP growth is pretty dramatic. If China, for example, has ten years to raise the consumption share of GDP by ten full percentage points (after which it would still be among the lowest-consuming major economies in the world), growth in consumption would have to exceed GDP growth by nearly two percentage points every year. To put this into numbers, if China expects GDP to grow by 4 percent a year on average over the next ten years, to raise the consumption share of GDP of GDP by ten percentage points would require that consumption grow by 5.9 percent annually, a growth rate China hasn’t seen except at GDP growths more than twice as high.