The Drying Land: Iraq’s Worsening Water Crisis

Introduction

Water is an essential part of the story of Iraq, also called the Land of the Two Rivers, where some of the world’s earliest civilizations came into being. The continuation of life and the development of the human saga in these parts of the world were, to a large degree, a product of the availability of abundant water, fertile land, and the ability of the people settling there to harness these resources and form complex societies around them. Yet what was once known as the Garden of Eden is now a barren desert. The resources that allowed people to live and thrive in Mesopotamia/Iraq are disappearing, leaving in their wake not only environmental devastation but also explosive social, economic, and political tensions.

Water shortage in Iraq is the result of several factors: poor infrastructure and limited state capacity; ongoing hydropower projects constructed upstream by Turkey and Iran; and worsening climate conditions that are affecting the Middle East and North Africa, including increased temperatures, severe and prolonged droughts, and a decline in precipitation levels. Some reports have predicted that, if climate threats are left unaddressed, the Tigris and the Euphrates, Iraq’s two main rivers, will run dry by 2040. The rivers, both of which originate in Turkey and pass through Syria before making their way to Iraq, are the source of about 98 percent of the country’s water supply.

That is alarming enough, but the ramifications will not end there. If Iraq’s water crisis is not met with a robust response, domestic turmoil will follow. A destabilized Iraq will have dire social, economic, and political consequences for its neighbors. Thus, immediate measures are required on the part of the Iraqi government as well as international agencies to address the issue of water shortage.

The Problem at Hand

Iraq’s water crisis spans the length and breadth of the country. In 2023, after four seasons of drought in Iraq, water levels at the Mosul Dam, which has a storage capacity ranging from 6 to 11 billion cubic meters, reached their lowest levels since its construction in 1986. Three submerged Yazidi landmarks surfaced for the first time in forty years. Experts believe that if no action is taken, Mosul Lake might soon run dry, leaving the 1.7 million residents of Mosul without power and water for crop irrigation. A 2021 report by the Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) predicted that in Nineveh Governorate, wheat production could drop by 70 percent.

Meanwhile, the Kurdistan Region of Iraq, which also lies in the north, is not faring well, despite diverse water sources compared to the rest of the country. The region gets its water from the Tigris, the Great Zab, and the Little Zab, as well as from rainfall and groundwater. However, less rainfall and the decline in water levels coming from Turkey and Iran impact water levels in many of the region’s main dams. Reports have found that the Dukan Dam, which provides drinking water for 3 million residents in Sulaymaniyah and Kirkuk and has a capacity of 7 billion cubic meters of water, holds only 2 billion cubic meters. Meanwhile, water levels in Sulaymaniyah’s Darbandikhan Dam have declined by 7 meters, making the dam operate at only a third of its capacity. The decline in water levels has devastated the region and its people, as evidenced by the decline in fishing, tourism, and agricultural production. The 2001 NRC report estimated that water shortages would reduce the region’s wheat production by half in the following year.

Iraq’s south, however, is where the situation is at its worst. While northern parts of the country have multiple sources of water and are close to the starting points of the two rivers and their tributaries, which grants them access to a larger water quantity and better quality, southern Iraq lacks these advantages. Moreover, water quality and quantity significantly diminish as the rivers flow south. Towns and cities in the central and southern parts of the country depend heavily on the Tigris and Euphrates for water—all the more so in recent years, with precipitation levels 40 percent below normal, according to some studies.

Additionally, because Iraq has limited and outdated infrastructure for managing industrial, agricultural, and petroleum waste, often that waste ends up in the rivers themselves, causing major health risks. In 2018, some 118,000 people were hospitalized in Basra city due to symptoms related to water pollution. The Iraqi Observatory for Human Rights found evidence that petroleum and oil pollution, medical waste, and wastewater directly go into the rivers. The decline in water levels and the increase in pollution has led to salinity levels in the Shatt al-Arab River that are ten times higher than acceptable World Health Organization standards.

Depleted water supplies, pollution, and increased salinization have also affected important ecosystems in the country. Efforts to restore the Iraqi marshlands post-2003 were fairly successful despite their destruction at the hands of Saddam Hussein’s regime in the early 1990s. The Marsh Arabs, also called the Ma’dan, are part of one of the world’s oldest living cultures and have lived on the land for generations. And the region’s biodiversity is such that it is home to twenty-two globally endangered species and sixty-six at-risk bird species. In 2016, the United Nations named the marshes a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

However, today, water levels have declined significantly, and seawater from the Gulf has intruded as far as 189 kilometers northward, destroying more than 24,000 hectares of agricultural land and 30,000 trees. The combination of environmental degradation and climate change has once again undermined the way of life of the communities in the area and the rest of southern Iraq, displacing many to the cities, where they have difficulty finding work. The World Bank’s estimate of a water deficit in Iraq of 20 billion cubic meters per year by 2030 could reduce the country’s gross domestic product (GDP) by up to 4 percent, or approximately $6.6 billion. The impact of the water shortage can already be felt on the ground. A study by the International Organization for Migration found that as of March 15, 2023, 12,212 families (about 73,272 individuals) remain displaced across ten governorates in central and southern parts of Iraq, and these numbers are only expected to increase with time if nothing is done.

The outcome of all this is that Iraq could go from being a water-stressed country to a water-scarce one. Both water scarcity and water stress are relative concepts that indicate a perilous condition: demand for water increases while water supply is affected by decreasing quantity or quality. Water stress refers to human-related limitations, such as outdated infrastructure, that undermine water availability and water quality. Water scarcity refers to a lack of freshwater resources. In the case of Iraq, the country used to receive approximately 30 billion cubic meters of water in 1933, which decreased to around 9.5 billion in 2023, with an expected availability per capita of 479 cubic meters by 2030, which would make the country water-scarce. Falkenmark water stress indicator, a country with water supplies below 1,700 cubic meters per person per year is water-stressed.

Internal Limitations and External Challenges

Iraq’s past and current climate crisis reflects changing global weather patterns and human-induced activities that intentionally and unintentionally destroyed the country’s environment and lowered its environmental resilience. Internally, the country’s decades-long dependency on the oil sector has produced a rentier system whereby, in return for obedience to the political leadership, citizens gain access to resources, a social safety net, and employment. Other sectors of the economy, such as agriculture, were deprioritized, eventually leaving the country with an outdated irrigation system and infrastructure.

These conditions only worsened with economic sanctions, wars, and internal conflict, leaving many water pumping stations that were built in the 1970s run down or even nonoperational and beyond repair. Outdated infrastructure also means that water treatment plants have long been neglected, which increases the pollution of waterways. According to the Environment Ministry, water treatment facilities in Baghdad meet the needs of only 5 million of the capital city’s 8 million residents.

Political actors in Iraq have scant interest in scrapping the rentier system. It is this very system that has since 2003 allowed them to build states-within-the-state, as well as militias and propaganda machines. Though climate change and environmental degradation in Iraq are not new, political elites ignored the issues until they became urgent and even now often seem disinclined to do much about them. For example, Iraq has yet to even begin to diversify its economy; this past decade, oil revenues accounted for around 99 percent of all exports, 85 percent of the country’s budget, and 42 percent of GDP.

The impact of the water crisis is felt mostly by the poor of the country, who are already experiencing limited economic opportunities and social and political marginalization. A 2022 study by the NRC found that 38 percent of the 1,341 households surveyed across five governorates reported increased social tensions over competition for resources and jobs, and many were forced to leave their community in search of job opportunities. These conditions are expected to worsen with time, as more families and individuals will be displaced to overpopulated cities with limited job opportunities and resources.

Many families displaced from rural areas in southern Iraq wind up in Basra, living in informal housing and excluded from the formal water and sanitation network. They tap illegally into the water network, further impacting the water infrastructure, and consume polluted water, thereby impacting their health and well-being. Long plagued by corruption and shoddy infrastructure, Basra is today one of the poorest and least developed cities in the country, despite the massive amount of oil on which it sits. Water infrastructure, as a result, is among the outdated structures in the city. Also, Basra is located at the end and the meeting point of the two rivers, which means that the water there is the lowest in quality and quantity. The temperatures are often exceedingly high, due in part to gas flares that periodically pollute the city skies and also increase water evaporation.

Iraq’s water problems are not only internal. External conditions play a very important role in limiting how much water the country receives. Iraq was considered water-rich until the 1970s, when Turkey began building a series of dams. Ever since, Turkey’s hydraulic projects have been an ongoing problem between the two countries, as they have reduced water flow to Iraq by 30–40 percent. Undeterred, Ankara has forged ahead with its projects—such as the Ilısu Dam, which opened on the Tigris in 2018.

Its hydraulic projects and their adverse effects on Iraq notwithstanding, Turkey itself is a water-stressed country—usable water per capita dropped from 1,652 cubic meters in 2000 to 1,200 cubic meters in 2023. Basically, a combination of mismanagement and worsening climate conditions has hit Turkey hard. In a press conference with Iraqi Prime Minister Mohammed Shia’ al-Sudani over water sharing between Turkey and Iraq, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan said that “precipitation in Turkey is at its lowest level in 62 years.” Turkey is likely to experience further water scarcity over the next few decades—which bodes ill for Iraq.

Syria is another country with its own water crisis. Reports found that in 2021, Syria had 40 percent less drinking water when compared to prewar years. The remaining water is highly polluted, which has led to a massive cholera outbreak. Between August 25, 2022, and February 15, 2023, nearly 100,000 suspected cholera cases were reported across all fourteen of the country’s governorates, with at least 100 deaths. Since the Tigris passes through Syria before reaching Iraq, water mismanagement and waste reduces the quantity, and impacts the quality, of what enters the country.

Iran’s water policy is another source of trouble for Iraq. Since the 1979 revolution, Iran has cultivated water-intensive crops such as sugar beet in order to become food self-sufficient and shield itself from Western dependency. To provide water for its increased irrigation needs, the government has constructed poorly planned dams and engaged in random well-digging. In 2021, the combination of such mismanagement of water resources and climate change resulted in one of the worst droughts the country had ever experienced. In 2022, Iranians took to the streets to express their anger over poverty, lack of economic opportunities, the treatment of women, and the water shortage the country is experiencing.

Over the decades, to address its increasing need for water and to calm the anger of its people, Iran has embarked on several projects that have had a detrimental effect on Iraq. Arguably the most harmful of these was construction of the Kolsa Dam to divert the Little Zab to feed Lake Urmia and the Sirwan River, both of which Iran relies on for irrigation. The Kolsa Dam has caused an estimated 80 percent drop in the water levels of the Little Zab. As a result, water levels in the Little Zab and Sirwan, both key tributaries of the Tigris, have dropped significantly. The impact of continued water mismanagement in Iran could be devastating for both Iraq and Iran, given that about two-thirds of Iran’s 10.2 billion cubic meters of water flow across its borders into Iraq.

The Road to a Water-Secure Iraq

While the level of the crisis is overwhelming, large- or even medium-scale solutions can arrest and even reverse the impending disaster. Addressing the structural limitations of the regime, such as corruption and inadequate decisionmaking, is essential in responding to the country’s climate and other related crises. For instance, the fragmentation of decisionmaking between state and local authorities on how to address water shortage, together with the main political parties’ uninterest in providing sufficient funding and support to the Ministry of Water Resources and the Ministry of Environment (from which they cannot extract major profits), means that decisions are often less effective when made.

Overhauling Iraq’s infrastructure is also imperative. Some steps have been taken in that direction. For instance, on the outskirts of Basra, the authorities recently completed a $200 million water desalination plant with support and funding from Japan. The project aims to provide water to 400,000 of the city’s 1.5 million inhabitants. A similar project by the U.S. Agency for International Development modernized water infrastructure for up to 650,000 people in Basra, and the United Nations Development Programme led reconstruction efforts for Mosul’s water infrastructure. These projects, most of which are undertaken by the international community, are key to sustaining a decent level of water quality and quantity.

However, efforts to address Iraq’s internal problems must include climate diplomacy with Iraq’s neighbors. In theory, this should not be difficult. A situation of collapse in Iraq is not in the interest of the country’s neighbors, given that instability can spread. Facilitating discussions among Iran, Iraq, and Turkey is an important step on the path to tangible cooperation. Iraq recently became the first country in the Middle East to join the Convention on the Protection and Use of Transboundary Watercourses and International Lakes, which aims “to ensure the sustainable use of transboundary water resources by facilitating cooperation across borders.” Additionally, Iraq signed the Paris Agreement in 2016 and ratified it in November 2021. The Paris Agreement is a legally binding international treaty focused on combating climate change.

More recently, the Iraqi government has increased its efforts to catalyze the conversation about climate change. In March 2023, Iraq hosted the Iraq Climate Conference in Basra. And in 2023, the country’s third international water conference, titled “Water Scarcity, the Mesopotamian Marshes, Shatt al-Arab Environment, Everyone’s Responsibility,” was held in Baghdad to discuss growing threats of drought and water scarcity between Iran, Iraq, and Turkey. However, it remains to be seen whether these conferences’ closing recommendations will translate into action.

In 2021, Turkey and Iraq reached an agreement declaring Ankara’s commitment to fair water flow and determined how much water Turkey must release to both Syria and Iraq. However, a Euphrates-Tigris basin-wide agreement has not yet been reached. Moreover, agreements aside, there remains the issue of implementation. International actors must work with the Iranian, Iraqi, and Turkish governments to ensure the implementation of existing agreements and further commitments to international and regional conventions.

Finally, the international community and the Iraqi state should support civil and political activists on the ground. These activists are the people best placed to spread environmental consciousness among ordinary Iraqis. They are part of the impacted communities and can organize them politically. Community pressure is a means to hound decisionmakers into addressing environmental degradation. At the same time, these activists often require protection. In February 2023, Jassim al-Asadi, a prominent environmental activist in Iraq, was kidnapped and tortured before being released two weeks later. Asadi’s ordeal highlights the threats activists face for bringing attention to climate issues, pressuring decisionmakers, and educating the public.

Conclusion

The water crisis in Iraq is the country’s new major threat. What makes this threat different from previous sources of instability is that it is the product of Iraq’s internal dysfunctions, its neighbors’ own limitations, and the global scourge that is climate change. What makes the water crisis in Iraq dangerous is its ability to drastically change the landscape of the country; impact its economic, political, and social stability; and even make some parts of it unlivable. The consequences of such a series of events would be felt beyond Iraq’s borders and cascade into the region and the world.

Current political and economic conditions show little indication that decisionmakers will take climate and water crises seriously and implement effective long-term plans, since these plans are likely to threaten the existing system and its beneficiaries. Even if decisionmakers do take serious steps to address the crisis at hand, the odds are low that such measures would prove effective, considering institutional limitations. However, this is not to say that Iraq is doomed. The knowledge that if Iraq’s water issues are ignored, then the country will be engulfed by instability may yet galvanize ordinary people and politicians into action.

The Politics of Environmental Activism: Lebanon’s Successful Save Bisri Valley Campaign

Introduction

On September 5, 2020, the World Bank officially notified the Lebanese government that it had canceled $244 million in funding for the Water Supply Augmentation Project, better known as the Bisri Dam project. The government had failed to meet three conditions: completing an Ecological Compensation Plan to offset biodiversity and ecosystem damage; hiring a contractor for the worksite no later than September 4, 2020; and finalizing the operation and maintenance arrangements for the project no later than August 24, 2020.

Located about 35 kilometers (approximately 20 miles) southeast of Beirut, the Bisri Valley entered the spotlight when, in 2014, the Lebanese government approved World Bank financing for what would prove to be a highly controversial project. Although the project’s cancellation was partly overshadowed by the devastating explosion at the Beirut port a month earlier, it was generally seen as a significant milestone for Lebanon’s environmental activists and residents in and around the valley.

The episode underlined that environmental concerns in Lebanon cannot be decoupled from politics. This may be true everywhere, since the relationship is at the heart of a movement that has gained prominence globally and that ties together environmental issues with justice. This connection was underlined in October 2021 when the United Nations Human Rights Council recognized “that having a clean, healthy and sustainable environment is a human right.” However, in Lebanon this connection had especial resonance because opposition to the Bisri Dam, organized by the Save Bisri Valley (SBV) campaign, took place amid protests against the country’s political class.

Starting in October 2019, Lebanese people went into the streets for several weeks of mass protests against the corruption of their sectarian political leadership. By building on the widespread disgust among the population with politicians and the way they conducted national affairs, the SBV campaign was able to transform a niche environmental issue into a reflection of broader popular discontent. In that way, it brought the Bisri project to the forefront of national attention, at least temporarily. The campaign also underlined that action tends to be more successful when activists manage to link their causes with other cases of contestation.

The Bisri Dam, Environmental Activism, and Politics

The Bisri Dam project goes back to the 1950s, when it was initially proposed by the United States Bureau of Reclamation to the then young republic of Lebanon. The idea behind the project was fairly straightforward, as Roland Nassour, the coordinator of the SBV campaign, has pointed out, namely “to funnel water to Beirut and its suburbs from the Bisri reservoir through water transmission lines.” This required the construction of a 73-meter-high barrier, as well as the expropriation of 570 hectares of “mostly agricultural and natural lands from around ten municipalities of the Chouf and Jezzine districts.”

The fact that the Bisri Dam project took decades to materialize did not mean that Lebanon opposed the idea of building a dam. In fact, dams continue to occupy “an almost idealized place” in Lebanon’s national water strategy, in the words of one local environmentalist. This emphasis on dams is true despite the fact that such structures have been criticized for decades because of their negative socioenvironmental impacts. The organization International Rivers summed up the criticism in a November 2022 press release at COP27: “Dams and hydropower schemes create major loss and damage, including producing significant amounts of methane, biodiversity loss, and community displacement.” In 2021, over 350 organizations from seventy-eight countries called on the United Nations to exclude hydropower dams from climate finance mechanisms.

In light of this attitude, the Lebanon Eco Movement, a coalition of over sixty environmental organizations and associations, first made public statements against the Bisri project in 2017, before launching the SBV campaign with other groups the following year. However, it was the October 2019 uprising that served as a catalyst for the campaign, as opponents of the Bisri Dam project made a conscious effort to tie their actions to the wider ferment taking place in the country. This choice contrasted with a similar campaign to stop the Qaisamani Dam project in Hammana, which began in 2013. There, opponents were able to mobilize the local community against the dam, according to Jibal, anongovernmental organization, but they failed to build a broader coalition. That is one reason why the project was able to go ahead.

SBV’s opposition to the Bisri project was prompted by its potentially dangerous repercussions. The authors of a paper published in Engineering Geology wrote that the dam would put “thousands of people and various structures at risk” and had a “high risk for protracted seismicity.” In addition, the SBV campaign pointed out that the dam threatened the Bisri Valley’s role as a habitat for migratory birds protected under the Agreement on the Conservation of African-Eurasian Migratory Waterbirds, to which Lebanon is a party.

However, it was the political impact of the dam that made the country’s leaders push back against the environmentalists. SBV coordinator Nassour explained the politicians’ motivations when he pointed out that dams “carry symbolic political meaning because they are an opportunity for politicians to claim that they are achieving something concrete.” In addition, like so many facets of Lebanese political life, the Bisri Dam project was caught up in sectarian politics. Indeed, the mayor of Mazraat al-Chouf, where the dam was to be located, is a member of the Progressive Socialist Party (PSP), formerly led by the Druze communal leader Walid Jumblatt. The party was an early supporter of the project, but it later reversed itself. This reversal may have been provoked by the fact that Gebran Bassil, who was then the energy minister, is also the head of the Free Patriotic Movement (FPM), with which the PSP has had an adverse relationship.

There was another dimension that was likely just as important. Bassil, the son-in-law of then president Michel Aoun, was a primary target of protesters in the 2019 uprising: one chant that insulted him personally was among the most popular in the streets. It was during his tenure as energy minister in 2010 that Bassil approved a new strategy for Lebanon’s water sector. This strategy included building fourteen dams, including the Bisri Dam, whose construction was ratified by the cabinet two years later; the World Bank promised funding two years after the ratification.

As the protests in October 2019 grew more prominent, the PSP saw an opportunity to withdraw its members from a government dominated by the FPM, Hezbollah, and the Amal Movement, thereby attempting to shield itself from public condemnation. By that time, the SBV campaign had become a part of the protests. Nassour told a journalist that the SBV campaign was a “clear reflection” of the principal slogan of the uprising, killon yaane killon, which in Arabic means “all of them means all of them,” in reference to the corruption pervading society. As the Bisri Dam was by then associated with the FPM and Bassil personally, the PSP sought to gain points by distancing itself from a project the party had once backed, with Jumblatt citing environmental concerns for his change of heart.

Environmental Activism and the Lessons of the SBV Campaign

There were several lessons from the success of environmental activists in preventing construction of the Bisri Dam. These were all the more valuable in that the political spaces for expression in Lebanon have steadily eroded over the years.

First, the SBV campaign underlined the fundamental link between environmental activism and politics, deriving from the inherent political dimension of many environmental issues in the country. Where political interests have often led to policies damaging to the environment, activists were able to turn the tables and exploit politics to impose their preferences.

The SBV’s successful linking of its campaign with the uprising of October 2019 showed the advantages of drawing on a broader protest movement to impose change. It also emphasized that playing on political rivalries could create valuable openings, since the political class in Lebanon, no doubt hypocritically, often seeks to project itself as being on the side of the public good. The SBV benefited from the PSP’s political divergences with Bassil and the FPM, but also from the PSP’s desire not to be tarred with the same brush as Lebanon’s other political forces, which had been main objects of disparagement by those demonstrating in the streets.

A second lesson of the SBV campaign pertains to the importance of adopting an intersectional and inclusive approach when addressing environmental issues. With global warming, these issues are sure to become ever more intertwined and multifaceted. Eco-friendly activism finds itself at the crossroads of a variety of concerns—environmental challenges that feed into each other, public and private corruption, and political interests that often undermine the well-being of the public. Unless activists can find a way of integrating their responses to such challenges and of thinking strategically, it will be difficult for them to accomplish their aims.

In 2019, Lebanon went through a situation that was a textbook example of how an environmental disaster can feed political contestation, which in turn reinforced environmental activism. Among the triggers of the uprising in 2019 were wildfires that occurred in the days preceding the protests. On October 13, they devastated large parts of the Chouf and Iqlim al-Kharroub regions in the mountains, as well as other localities south of Beirut. The state handled the initial response very poorly, in part because it had failed to adequately maintain firefighting helicopters. The fires were extinguished thanks to foreign assistance, including helicopters sent by Cyprus, Greece, Jordan, and Türkiye, as well as to local efforts to combat the blazes by ordinary Lebanese, Palestinian, and other civilians and, finally, to rain. The state’s response provoked great indignation, which in turn was a contributing factor in the nationwide demonstrations several days later, lending momentum to the SBV campaign in the months that followed.

The SBV campaign also found success in its attempts to appeal to a cross section of Lebanese society. This was not always true of Lebanon’s environmental movement, which was often primarily a middle-class phenomenon. As Karim Makdisi has written, “the main inspiration and impetus for these pioneer environmentalists—mostly professional, middle class, and Western educated . . . was the success of the environmental movement in Europe and North America during the 1960s that culminated in the 1972 United Nations Conference on the Human Environment in Stockholm.”

Why would a heavily middle-class movement be problematic? First, because it is invariably better for activists to pursue their objectives as part of the broadest possible coalition of social forces and categories. Second, climate justice requires that the voice of the most vulnerable groups be heard. Environmentally damaging policies often impact the most defenseless in society most severely. It is important, therefore, that environmental activism include a cross section of the population, so that all sides of the story can be represented.

While it was arguably a middle-class phenomenon initially, the SBV campaign did seek to appeal across social strata when it grasped that opposition to the dam included thousands of people from varied class and sectarian backgrounds in the Chouf, Jezzine, and Sidon regions. This it did by forming WhatsApp groups, which allowed neighbors to learn about one another in ways that were not possible previously and to find common cause against the Bisri project.

As Lebanon’s social environment is changing, the predominantly middle-class nature of Lebanese environmental activism has to be updated. The country’s financial and economic crises have led to the pauperization of an already relatively small middle class, and income and wealth inequalities continue to increase. As living conditions have deteriorated, social disparities will likely widen. It remains to be seen whether future protests and other forms of contestation will bring people from diverse backgrounds together or whether divisions will remain or be exacerbated, thereby weakening the wide appeal of activist networks.

A model to follow can be what was implemented in September 2022 in the Akkar region of northern Lebanon, where at least eighty Lebanese and Syrian women and men from fifteen villages formed a team of volunteer firefighters. Along with the Beqaa Valley, Akkar is Lebanon’s poorest region, and residents there are strongly aware of it. While the Lebanese state and a significant percentage of the population continue to scapegoat Syrian refugees in the rest of the country, in Akkar, time and time again Lebanese and Syrians have cooperated closely. The volunteer firefighters are an example of the “solidarity not charity” principle of mutual aid—when a group from a community sets up to serve that community.

A third lesson learned from the SBV campaign is that environmental activism is greatly reinforced if activists can unite around practical solutions for the issues they are addressing. Otherwise, they only leave space for members of the political class to impose solutions of their own that serve their interests but that are inadequate for protecting the environment and the public. Indeed, SBV as well as independent scientists proposed alternatives to the Bisri Dam, alternatives that would “[harness] Lebanon’s natural and geological advantages.” These included making more efficient use of underground water resources, reducing water loss (which can reach up to 50 percent in some areas) in the distribution network, as well as building “small to medium-sized urban collective storage ponds.” While these proposals were valuable, they were not presented in a cohesive and systematic fashion, leaving room for politicians to propose new water projects that would only benefit themselves.

A good example of the negative outcomes of failing to propose solutions is an environmental campaign that took place in 2015, following the closure of Lebanon’s largest landfill and the consequent accumulation of waste in Beirut and Mount Lebanon. This gave birth to a protest campaign known as You Stink, launched by independent environmentalists and activists. 1 Although the campaign drew large crowds—which were surpassed in size only by the uprising in 2019—it lost momentum after a few months and failed to change the government’s waste disposal model. This was due, at least in part, to the lack of a unified set of demands.

However, the You Stink campaign did have other significant repercussions on civic activism, particularly in potentially bringing to office people who could present policy solutions to environmental and other problems. The campaign is generally credited with having provided the spark for the establishment of the Beirut Madinati (Beirut My City) list in the municipal elections of 2016. Beirut Madinati united a number of civic activists who had no experience of traditional Lebanese politics. While it failed to win a seat on the Beirut municipal council, the list garnered a high number of votes, showing its appeal to many voters. Indeed, it could be argued that Beirut Madinati was the wedge that allowed civic activists to enter Parliament in the general elections of 2018, where they managed to form a sizable legislative bloc.

As Mona Fawaz, one of Beirut Madinati’s founders, noted: “When protesters’ demands weren’t heard [in the You Stink campaign], activists began to debate the next steps, with some suggesting participation in local elections.” However, You Stink’s most active participants were not all immediately in agreement with shifting the focus toward municipal elections, Fawaz continued, and most only came on board after Beirut Madinati was fully established.

There are two main conclusions from the You Stink experience. The first is that any separation between the environment and politics is artificial insofar as environmental justice is concerned. The disposal of solid waste is highly lucrative, and many politicians were partly funded from the revenues derived from this in different Lebanese regions. So, when the landfill was closed, they were keen to find other ways of ensuring they could finance their patronage networks from any new system put in place. This undermined any notion of environmental justice, as the Lebanese state would continue to adhere to an archaic waste management system that still damages the environment and is detrimental to citizens’ health.

This reality has only reaffirmed how Lebanon’s politicians and parties have long reduced the environment to the exploitation of its lucrative resources and an extension of their sectarian political interests. This was especially true in the Bisri Dam case. In the valley where the project was to be located, the political dominance of the PSP devalued the inherent worth of the land—its soil, trees, rivers, and wildlife—fitting it into a more sectarianism-friendly framework. Such dynamics have been repeated time and time again throughout Lebanon.

Separating the environment from politics is better understood as the depoliticization of that which is inherently political. To Lebanon’s politicians, the Bisri Dam project would have unlocked $244 million that could have been diverted to political, or personal, use. The corruption of Lebanon’s political class has long been noted in reports on the country. For instance, a 2022 report from the Reform Initiative for Transparent Economies stated, “Some of the challenges to international funding in Lebanon relate to the country’s known corruption problems and its slow pace of reforms.” (The word “corruption” was mentioned thirty-two times in the eighty-three-page report.) According to the same report, in 2019 an EU Parliament resolution on Lebanon “strongly deplored the extremely high level of mismanagement and lack of financial oversight over funds delivered in the past.” To this day there is no clear understanding of how much international funding enters into private hands.

Conclusion

The SBV campaign, like the You Stink campaign before it, exemplified the inherent relationship between the environment and politics. For this reason, environmental activists would benefit from adopting an environmental justice approach as this might help them to navigate the complex political and economic currents that they will invariably face.

Indeed, the SBV campaign went beyond opposing construction of the Bisri Dam as it sought to appeal to wider grievances directed against the political establishment, blurring the line that separates environmental activism from the public interest and politics. Similarly, You Stink, which emerged from a waste management crisis, linked environmental advocacy with wider political objections. The fact that it drew large crowds and influenced phenomena such as Beirut Madinati affirmed the importance of that intersection. Its short-term gains are often debated, but You Stink had a lasting impact on Lebanon’s political scene.

The Bisri Dam campaign, like the waste management crisis that sparked the You Stink campaign, was a microcosm of the Lebanese sociopolitical system, in particular the perennial race for resource extraction. The abuse of Lebanon’s natural heritage in yet another battle among members of the country’s political elite ignored the apprehensions of affected residents and environmental advocates. Instead, the environment became a proxy battleground for larger political issues, in which the public’s right to have a say in a common concern of all states was disregarded. In light of this, seeking environmental justice is the best path to focus activists on a clear, final objective, making them better able to resist all efforts to derail their actions.

Notes

1 The author was one of the organizers of the You Stink movement until September 2015.

Climate-Proofing for Groundwater Management in Oman

Introduction

Climatological natural hazards have become a critical problem in arid and semi-arid areas like Oman. Converging factors—including the dry climate, extreme temperatures, limited seasonal rainfall, and vast expanse of desert—have caused various economic losses and social impacts. Prolonged drought, another recurring feature of arid climates, can also affect the water sources that feed aquifers.

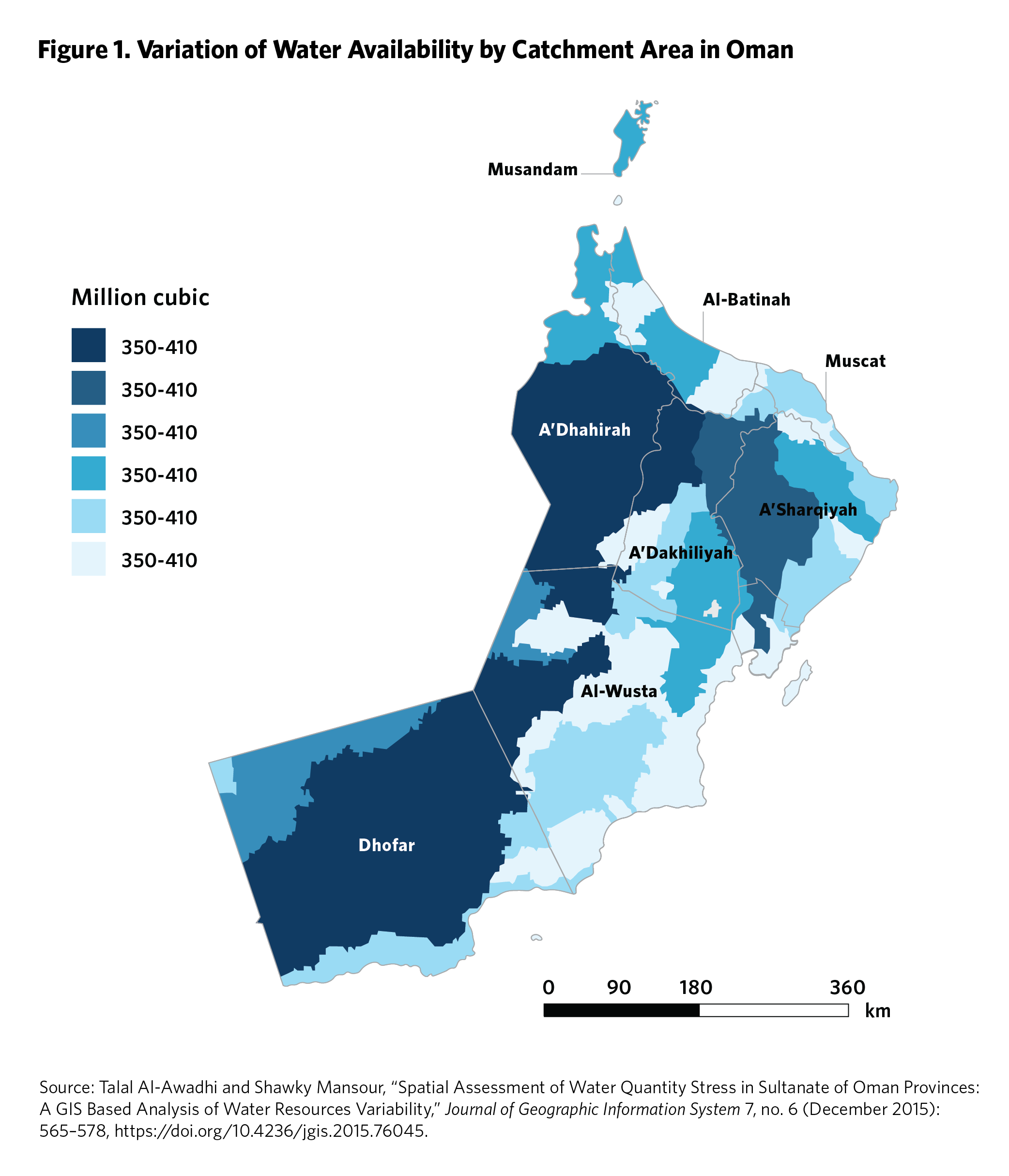

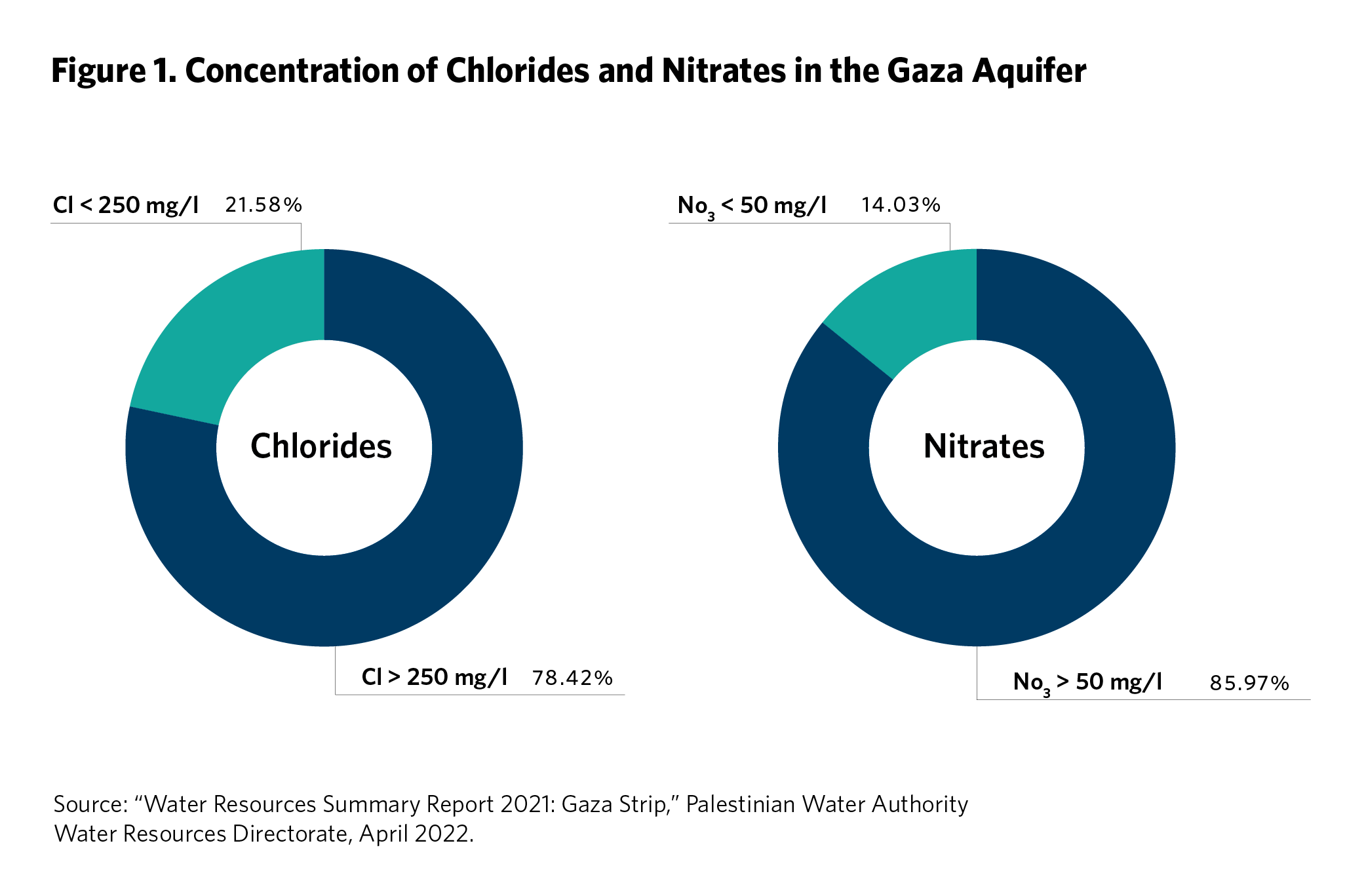

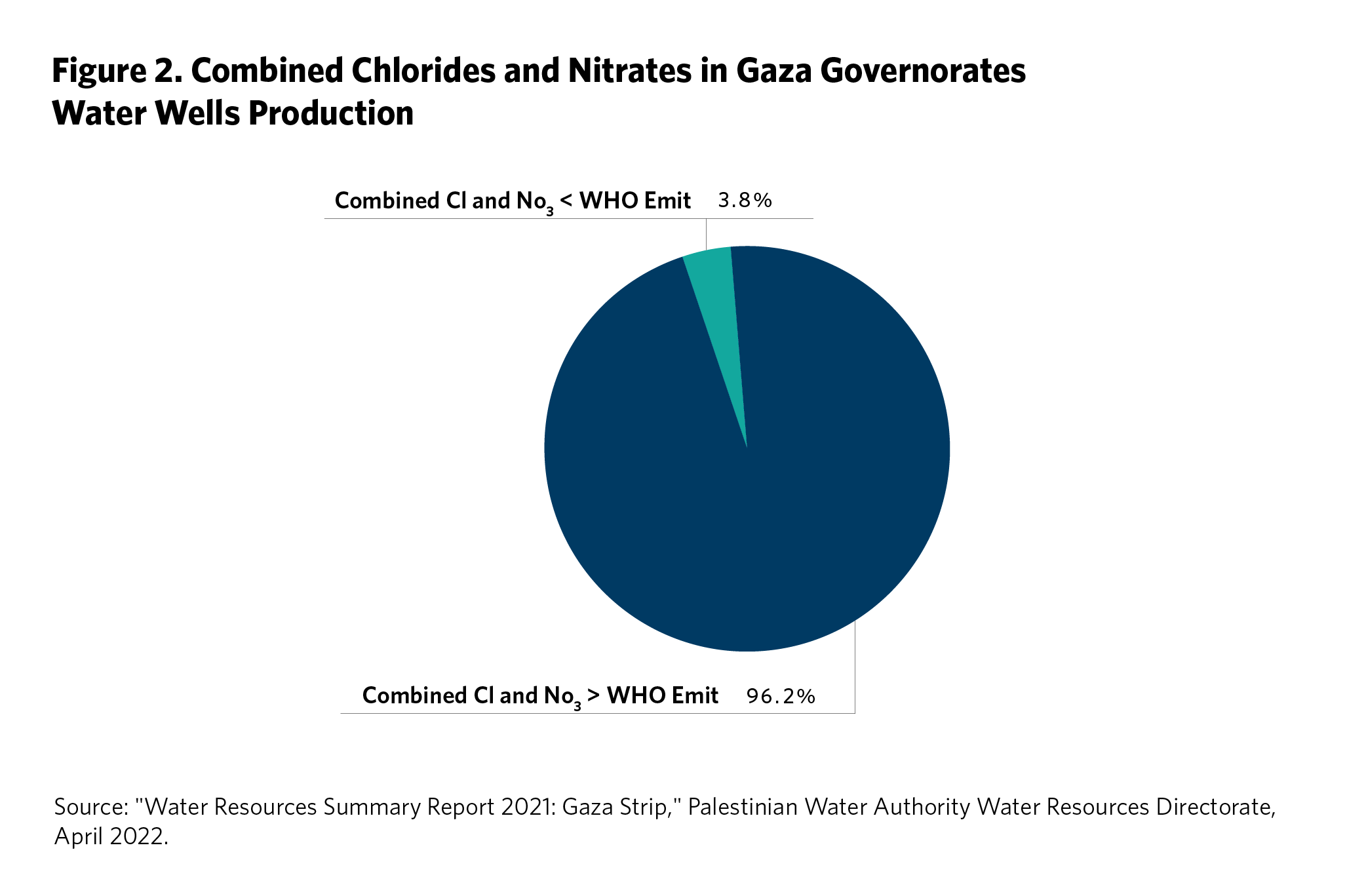

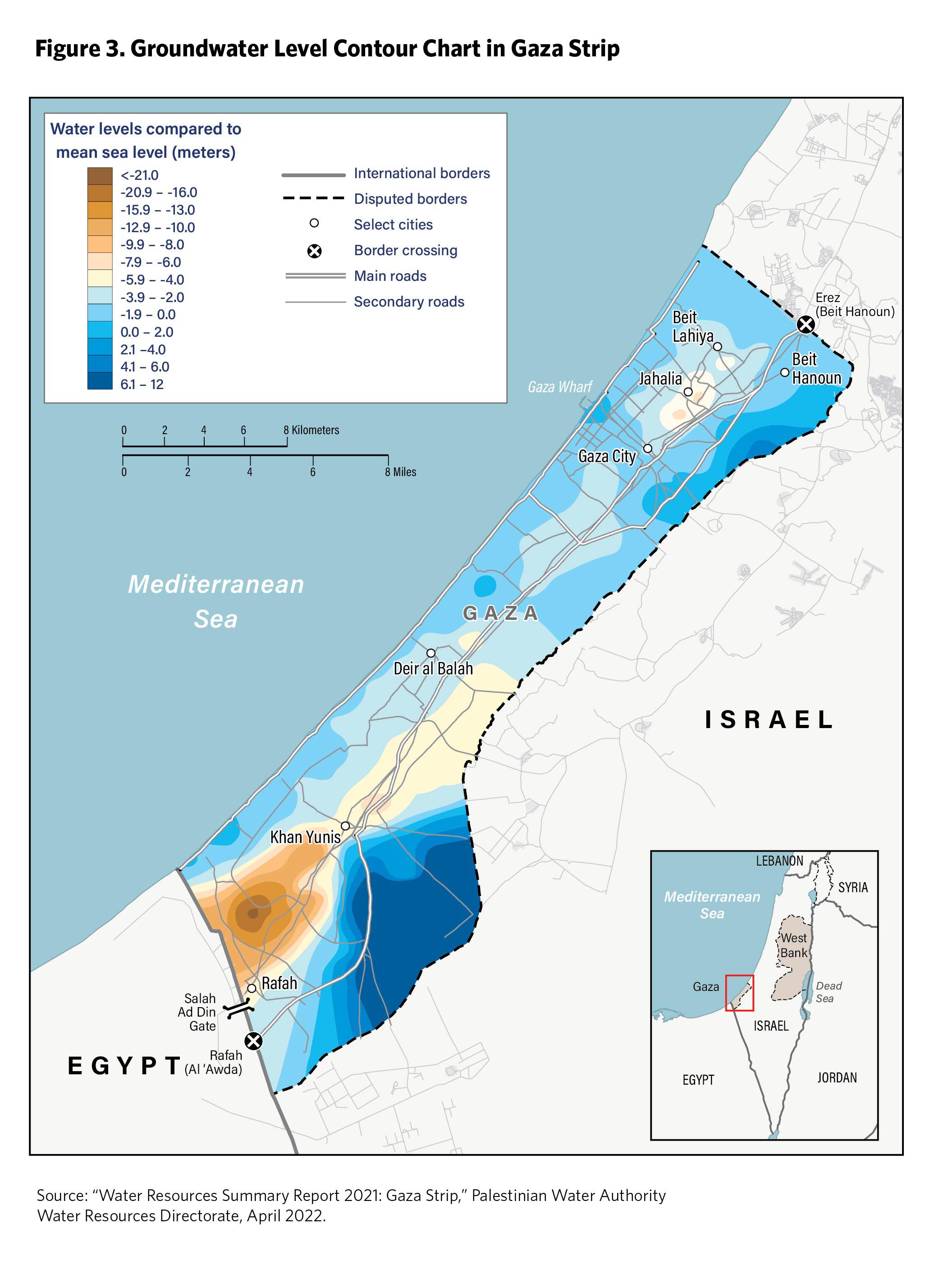

Oman is particularly susceptible to these climate hazards. Large areas of the country lack water resources; in parts of the north, water can only be obtained from traditional man-made water channels known as falaj. The country also has limited freshwater resources, making aquifer water its primary source for irrigation and freshwater. Several aquifer systems—including the carbonate aquifers in the northern and central Hajar Mountains, the sandstone aquifers in the eastern and southern mountains, and the alluvial aquifers in the coastal plains and valleys—are essential water sources for Oman, providing groundwater for domestic, agricultural, and industrial purposes. Unfortunately, the rising demand for groundwater, combined with the effects of climate change, is driving the mass consumption, salinity, and pollution that threaten the country’s vital aquifers. This has raised significant concerns over the ways that climate change will intensify impacts on groundwater. Figure 1 illustrates the variation of water availability per catchment area in Oman.

This chapter explores the impact of climate change on water resources in Oman and the institutional perspectives and policies for managing water resources in Oman.

Climate Change and Water Challenges

In its Fifth Assessment Report, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) notes that climate change will reduce renewable surface water and groundwater resources, intensifying competition for water above and beyond other factors like population increase, land-use change, pollution, and inadequate practices of water resources management. Climate change will also increase the risks of submergence, coastal flooding, and coastal erosion in coastal systems and low-lying areas. In its Sixth Assessment Report, the IPCC says, “Groundwater recharge in some semi-arid regions is projected to increase, but worldwide depletion of non-renewable groundwater storage will continue due to increased groundwater demand (medium to high confidence). The IPCC also estimated an increase in the annual global proportion of intense tropical cyclones (rated categories 3 through 5) by roughly 1 to 10 percent, assuming the global temperature rises by 2 degrees Celsius. More severe tropical cyclones will likely occur in the Arabian Sea, although the global frequency will either decrease or remain unchanged. Oman is located in the coastal line of the Arabian Sea and is affected by the Arabian Sea cyclones in two seasons: pre-monsoon and post-monsoon. The records show increased tropical cyclone intensity in the Arabian Sea, with many landfalls in Oman.

Furthermore, since 2007, the number of tropical cyclones categorized from 3 to 5 degrees that made landfall in Oman increased. For example, in 2019, Cyclone Shaheen made landfall in north Oman on a rare track through the Sea of Oman. The last recorded cyclone on the same track was in 1890. The cyclone caused a catastrophic disaster in the affected area because of the severe flash flood. Thehigh recorded rainfall on the day of the landfall was 350 milimeters in ten hours. Cyclone Guno 2007, a category 5 storm, was the only cyclone recorded in the last one hundred years in the Arabian Sea and made landfall in north Oman, causing massive damage in Muscat.

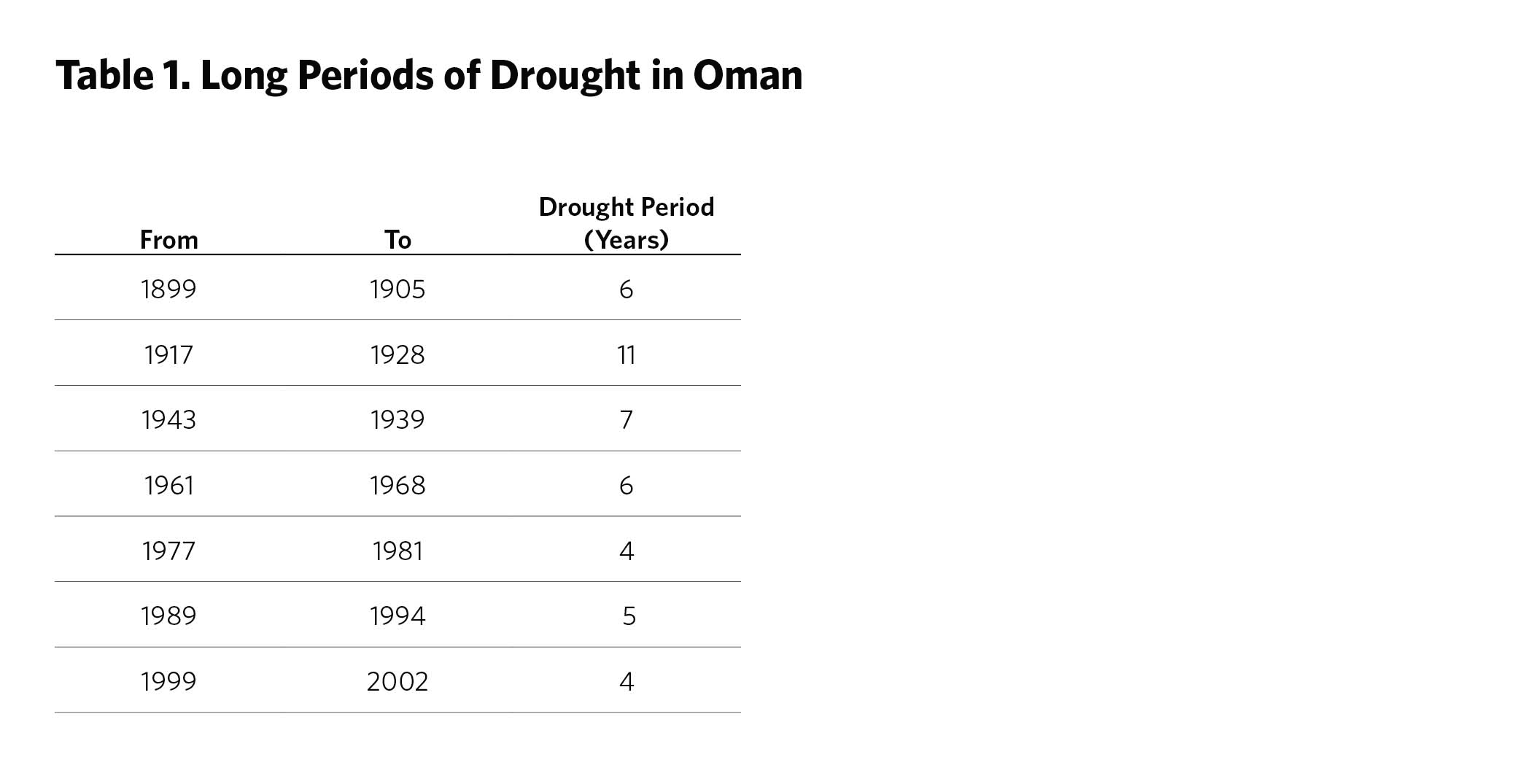

Consequently, climate change can alter precipitation patterns, impacting Oman’s amount, intensity, and rainfall distribution. Decreased precipitation or changes in rainfall patterns reduce recharge and worsen water scarcity issues, affecting groundwater recharge rates and the replenishment of aquifers. Records show that Oman has already gone through prolonged drought seasons several times (see table 1).

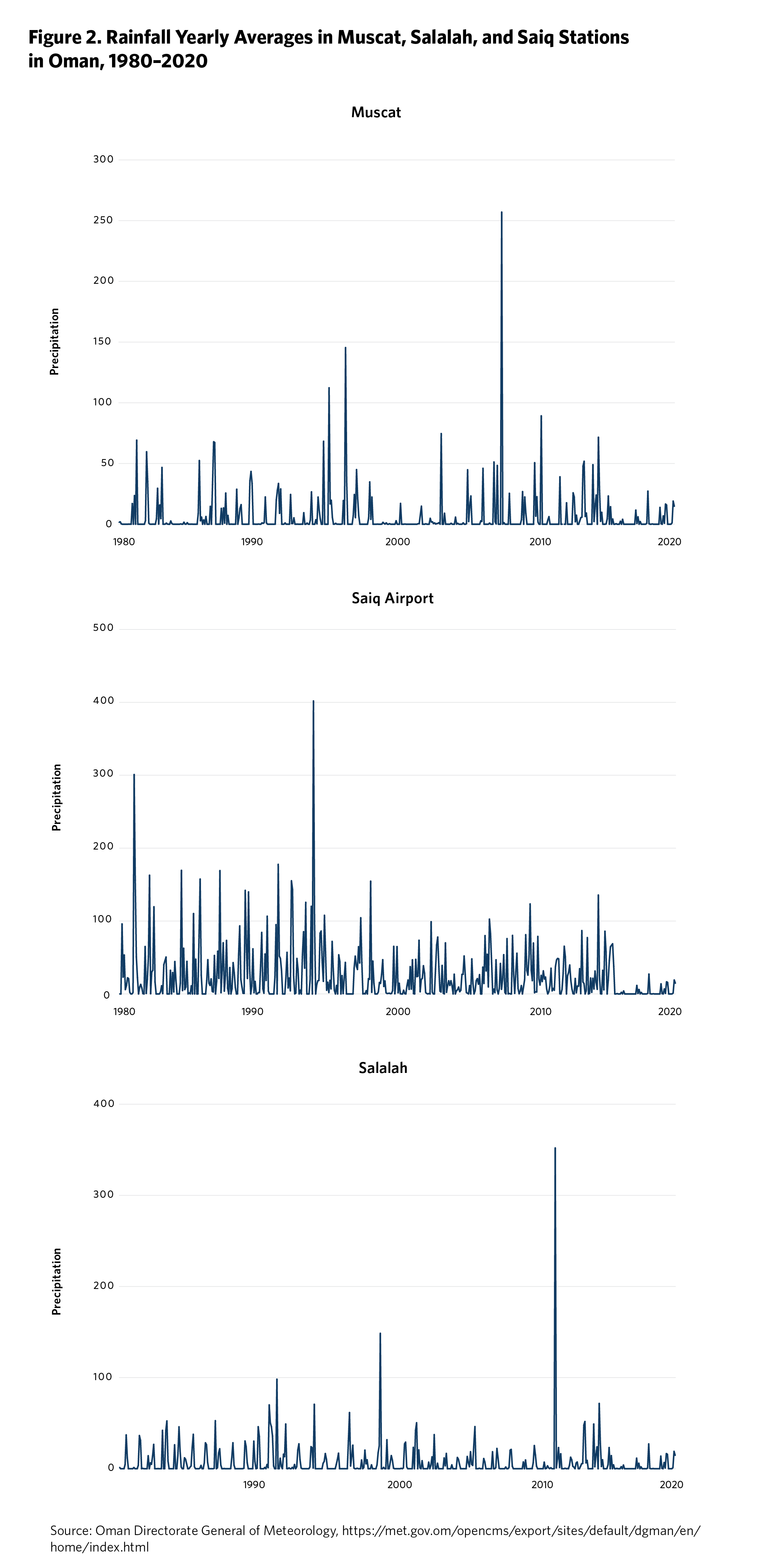

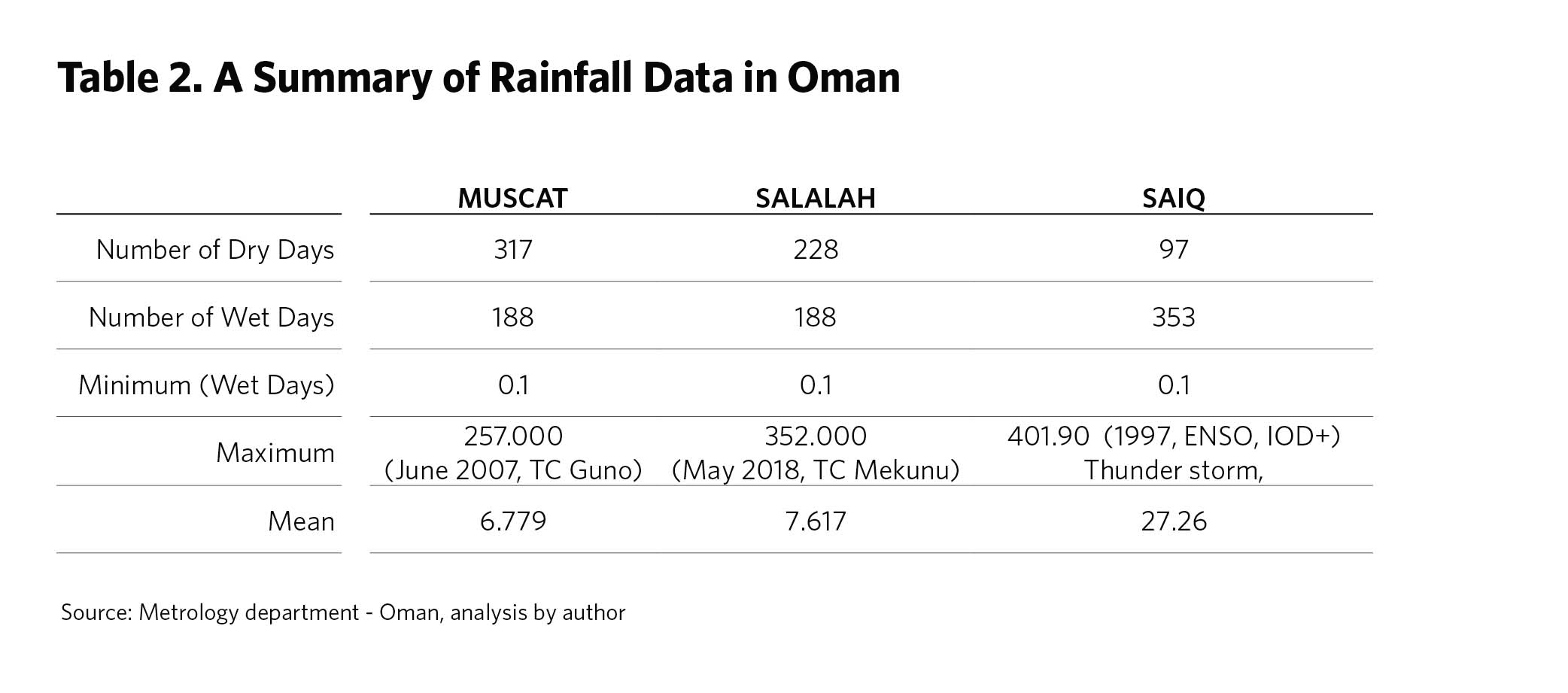

Rainfall in Oman is already unstable and largely limited, with periods of extreme rainfall in some years. Figure 2 illustrates the variability of rainfall at three different stations in Oman (Muscat, Siaq in the eastern Hajar Mountains, and Salalah in the south of Oman). Table 2 summarizes rainfall data from the same three different stations between 1980 and 2020.

The droughts in Oman have socioeconomic impacts on local people, especially in regard to the irrigation system, farming, and grazing animals in local Omani villages. At the same time, historical records show that the frequency of high-intensity tropical cyclones making landfall in Oman has increased. These tropical cyclones, which can cause severe flash flooding and extreme winds, have wreaked massive damage to Oman’s infrastructure several times. But despite the risk of damage, severe weather events positively impact aquifers in Oman. For example, according to experts, tropical cyclone Shaheen in 2021 increased the amount of groundwater in the Al-Batinah aquifer. Altogether, the groundwater recharge volume may actually be more stable and sustainable.

The groundwater recharge in Oman occurs through rainfall and flood flow infiltration, which refers to flash floodwater that remains on the surface for a few days but eventually seeps back into the ground. However, recharge rates vary widely across the country due to differences in precipitation, geology, and land use. Also, rising temperatures associated with climate change can lead to increased evaporation rates, causing more water to be lost from aquifers. Higher evaporation rates can result in decreased water availability and further depletion of aquifer storage. Aquifer depletion is a significant issue in Oman, particularly in the coastal areas where groundwater is pumped at unsustainable rates. According to a Ministry of Regional Municipalities and Water Resources study, the water table has dropped by 10 meters in some areas over the past few decades.

Salinity is also a critical issue in Oman as a result of the poor management of its irrigation systems. Groundwater from aquifers is extracted through wells for various purposes, including drinking water supply, irrigation for agriculture, and industrial use. However, the overexploitation of aquifers can lead to a depletion of water resources and the intrusion of saline water into freshwater aquifers, making the water unusable. Sea-level rise can also exacerbate saltwater intrusion into coastal aquifers. As sea levels rise, saline water can infiltrate coastal aquifers, making the groundwater unfit for use. This may pose significant challenges for water resource management in coastal areas of Oman. For example, increasing water demand for agriculture and for domestic, industrial, and tourism purposes is the leading cause of the deterioration of the Salalah coastal 'aquifer's water quality. Additionally, the lateral intrusion of salty water from limestone rock on the eastern and western sides of the aquifer has caused salination in the central part of the aquifer.

Water Resources and Regulations in Oman

Oman is classified as a water-scare country with limited freshwater resources and a limited annual average rainfall estimated at 100 millimeters. The sustainable management of aquifers is vital for meeting the country's water needs. The annual renewable freshwater supply is approximately 330 cubic meters per capita. Groundwater is the primary source of approximately 70 percent of total water use in Oman. Limited rain tends to fall only over small areas and does not provide enough water for dryland—or nonirrigation—cultivation. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, groundwater is the leading and most reliable water source across Oman. However, there are also some significant sources of surface water in wadis, such as Daygah and Quriyat in north Oman, which have an average flow of 60 million cubic meters per year, and Halfayn, which has a large catchment area of over 4,000 square kilometres.

Irrigation water is obtained primarily from shallow aquifers and from the flow of underground dry-flow pathways. But the rising demand for groundwater, combined with the effects of climate change, has strained the country’s aquifers. Underground water, too, is being depleted at an unsustainable rate due to overextraction and lack of regulations.

The recently announced Royal Decree 40/2023 regulates the water and sanitation sector. The law defines eleven activities that are required to obtain prior approval, including water production, transportation, and distribution, as well as sewage collection, transportation, treatment, and disposal. It also aims to improve the waste-disposal system by preventing waste disposal from commercial, industrial, agricultural, or medical activities without prior approval. Other provisions of the law, which apply to producing, transporting, or supplying healthy water, will help improve well water.

In addition, the new law is intended to explore and develop alternative water sources to reduce reliance on vulnerable supplies, enhance water storage to mitigate the impacts of changing precipitation patterns and droughts, and develop measures to protect water quality from pollution and contamination. This may involve implementing best practices for managing agriculture, industry, runoff, water bodies, and ecosystems. The law is also meant to help foster collaboration and engagement with stakeholders, including local communities, water users, and relevant authorities, to raise awareness about climate change impacts on water resources and involve them in decisionmaking. Through robust monitoring systems, authorities will be able to track changes in water resources and the effectiveness of new measures, as well as regularly review and update water management strategies based on new information and changing climate conditions. Finally, the law will strengthen the ability of water-management institutions to integrate climate change considerations into their policies and practices.

Climate-Proofing Oman

Climate-proofing is a new approach to understanding the impacts of climate change on development by identifying the best measurements to reduce climate change vulnerability in a given area. The United Nations Development Programme describes climate-proofing as

“a shorthand term for identifying risks to a development project, or any other specified natural or human asset, as a consequence of climate variability and change and ensuring that those risks are reduced to acceptable levels through long-lasting and environmentally sound, economically viable, and socially acceptable changes implemented at one or more of the following stages in the project cycle: planning, design, construction, operation, and decommissioning.”

In other words, it means integrating the political, social, and economic risks and opportunities in different climate change scenarios directly into infrastructure design, operations, and maintenance.

Climate-proofing water management requires strategies and measures to ensure that water resources and systems can withstand and adapt to the impacts of climate change. Like climate-proofing in general, climate change considerations must be integrated into planning, designing, and operating water-management infrastructure and practices. The process comprises two pillars (mitigation and adaptation) and two phases (screening and detailed analysis).

Climate-proofing water systems in Oman can be done through the following steps.

- Conduct a comprehensive assessment of a water system’s vulnerabilities to climate change. Understanding the risks that Oman faces—including increased temperatures, changing precipitation patterns, sea-level rise, and extreme weather events—is essential for better water-management policies. It also helps to identify areas at high risk of groundwater depletion and other perils like pollution caused by development policies.

- Develop water-management plans for different climate change scenarios and consider their potential impacts on water availability, quality, and infrastructure. This contingency planning includes considering changes in water demand, optimizing water allocation, and identifying alternative water sources. Oman is keen to implement a regulatory framework for the management and use of groundwater by applying water quotas to monitor aquifer depletion. The highest priority is given to depleted areas in the coastal plain of the Batinah region in northern Oman, where demand for groundwater is especially high.

- Promote water conservation and efficient water-use practices to reduce demand, increase the resilience of supplies, and enhance efficiency. This conservation can include implementing water-efficient technologies, promoting water-saving practices, and implementing demand-management measures.

Conclusion

Oman’s limited rainfall and scarce water resources make it particularly vulnerable to the effects of climate change. The country’s dependence on aquifers has strained the water supply and exacerbated its mounting water crisis. In the face of a changing climate, ensuring the sustainable management of water resources is essential.

Climate-proofing Oman’s water-management strategy is a substantial step toward building resilience. Doing so will require a multifaceted and integrated approach that considers each region’s unique characteristics and water system. But by strengthening water risk assessment tools and stakeholder mapping, the country can design response strategies at the watershed level and shift from only managing risk to seizing opportunities for better water management.

Adapting to Climate Change in Conflict-Affected Syria

Introduction

Along with twelve years of war, Syria has experienced climate change, drought, destruction of critical infrastructure, weak government institutions, and a drastic decline in the water level of the transboundary Euphrates River, which flows into Syria from Türkiye. This has led to water, food, and energy insecurities that have caused and continue to cause enormous human suffering. Additionally, food shortages, inflation, and high grain prices on the international market due to the Ukraine war have contributed to the soaring cost of food items. And the earthquake in southern Türkiye and northwestern Syria in February 2023 aggravated the humanitarian crisis and increased the risk of cholera, hepatitis, and norovirus, as well as food insecurity.

Today, 12 million Syrians are food-insecure, an additional 1.8 million are at risk of food insecurity, half the population is water-insecure, and over half a million children suffer from chronic undernutrition. With 90 percent of Syrians living in poverty and 15.3 million people in need of humanitarian assistance, families have withdrawn their children from schools and opted for unhealthy coping skills, such as skipping or severely limiting meals. This perpetuates the cycle of poverty that threatens human capital and weakens any chance of future economic prosperity for the nation. The health, safety, and future of the most vulnerable members of the community—children, girls, and women—are being compromised.

Given these desperate conditions, humanitarian organizations and domestic political institutions must work to enhance Syrian society’s ability to withstand climate change and droughts. Otherwise, millions of innocent civilians will continue to confront food, water, and energy insecurities, along with social and political instability. Indeed, even as Syria attempts to bring an end to the war, efforts at postconflict reconstruction must take into consideration the need to build adaptive capacity to climate change. In addition, the international community should encourage Türkiye, whose dam-building projects along the Euphrates River and increased water consumption have drastically reduced downstream water levels, to comply with its 1987 protocol with Syria regarding the river. Following these steps would help to avert further suffering and increase the possibility of a peaceful future for Syrians.

A Perfect Storm: Climate Change, Droughts, and War

Syria has experienced climate change for over a century, but the impact is growing. While the country’s temperature increased by 0.8 degrees Celsius (1.4 degrees Fahrenheit) over the past century, climate change models project an additional increase of 3–5 degree Celsius (5.4–9 degrees Fahrenheit) by the end of this century. Precipitation, which has already decreased across Syria, is expected to continue to decline. Drought is already devastating the region and is set to increase in both frequency and duration. And, due to the impact of climate change, the water level of the Euphrates is expected to decrease by 23 percent. Combined, all this means that Syria is projected to experience a 20 percent decrease in its overall water supply by 2050.

The 2020–2022 drought led to water shortages across Syria, especially the breadbasket governorates of Hasakeh, Deir Ezzor, and Raqqa. The drought and erratic weather patterns contributed to a 90 percent failure of rain-fed crops. For example, Syria’s wheat production, which is essential to meeting domestic food security, declined from 2.8 million tons to 1 million tons, a 75 percent drop from precrisis levels. Such crop failure decreases the supply of essential grains and animal feed and increases food prices. It also threatens the livelihood of agricultural workers. The agricultural sector employs 14.6 percent of the population in Syria. And approximately half the population in rural areas depends on this sector for its livelihood, with little opportunity for alternative employment except the security sector, militias, and construction. In their desperate search for jobs and livelihoods, young men, women, and even children provide fertile ground for extremist movements to recruit members.

The combination of repeated crop failure, economic crisis, inflation, and the impact of the war in Ukraine on world grain costs has resulted in a spike in food prices in Syria. Between 2020 and 2022, the cost of food increased by 800 percent, which is the highest rise since 2013. High food prices and poor economic conditions led the Food and Agriculture Organization to classify Syria as a hunger “hot spot” and a place of high and continued concern. In 2019, 36 percent of the population was food insecure; by 2022, this had climbed to 55 percent, about half of them civilians in rural areas. And then the earthquake struck. In northwest Syria, the area most affected by the earthquake, 3.1 million out of 4.1 million people were food insecure prior to its occurrence, a figure that increased significantly afterward.

Years of warfare during which Russia, the Syrian government, and the Islamic State group targeted hydrological infrastructure—including 60 percent of water treatment plants, water towers, and pumping stations—have resulted in the destruction of 50 to 95 percent of Syria’s irrigation systems and consigned half the population to water insecurity. Moreover, when Türkiye’s military entered northeastern Syria in 2019, it took control of the Alouk water station, the primary source of water for 1 million people. The electricity needed to operate the water plant comes from a region under the control of the Kurdish-dominated Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), and any maintenance or repair of the Alouk station requires the intervention of outside technicians—and therefore international mediation. From August 2021 through March 2022, the station operated at half capacity 80 percent of the time, and between September 2022 and March 2023, it failed to operate. Separately, because of the destruction of wastewater treatment facilities, 70 percent of sewage in Syria is discharged into the environment untreated, contaminating both surface and groundwater.

Desperation for water is driving 52 percent of families to use unsafe water, which contributes to waterborne diseases. The World Health Organization estimated a 50 percent increase in acute diarrhea in Hasakeh and Raqqa Governorates during the first six months of 2021. Unsafe drinking water has also resulted in a cholera outbreak, with 100,000 suspected cases and 100 deaths in the country by April 2023. Across Syria, approximately 6.5 million people are at high risk of contracting cholera. Shortages of electricity and water are also compromising the health system’s ability to function; only 59 percent of hospitals in Syria are fully functioning.

Ineffective and weak governing institutions that fail to respond to increasing domestic poverty and deprivation contribute to political tension and social turmoil. For example, to avert a humanitarian crisis amid climate change and droughts, a stable state could increase subsidies to farmers facing financial collapse and to poor segments of society, and it could also import grain, even if this is costly, to offset domestic shortages. However, a conflict-affected weak state such as Syria, with its limited foreign reserves, confronts significant challenges in its ability to increase grain imports or underwrite the soaring cost of food subsidies for the poor. The government of Syria currently controls approximately two-thirds of the country—mostly in the south, center, and west. Its power is contested in part of the northwest by the Islamist militant group Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham, in the north by Türkiye and its Syrian proxies, and in the northeast by the SDF. Government institutions in these areas are weak, ineffective, and unable to provide residents with much-needed social safety nets.

The Problem Upstream: Türkiye’s Dams

Predominantly arid and semi-arid Syria is highly dependent on the transboundary Euphrates River for meeting the country’s water and energy needs. Since the 1960s, Türkiye has undertaken extensive development by building dams along the Euphrates and extending irrigation networks throughout southeastern Anatolia. Known by its Turkish acronym, GAP, this multifaceted project also covers the neighboring Tigris River and consists of twenty-two dams, nineteen hydroelectric power plants, and the irrigation of 1.8 million hectares (nearly 4.45 million acres). As of 2023, Türkiye had completed eighteen of its planned dams along the Euphrates and Tigris Rivers and 54 percent of its irrigation projects.

Much of this development is contentious. In 1987, Ankara and Damascus signed the Protocol on Matters Pertaining to Economic Cooperation. The protocol committed Türkiye to discharging 500 cubic meters (654 cubic yards) per second of water into Syria. In the past few years, however, Syria has received only around 200 cubic meters (262 cubic yards) per second. During the 2020–2022 drought, Türkiye met its irrigation needs in southeastern Anatolia by reducing the amount of water flowing downstream, which contributed to crop failure in Syria. Another result was that the Euphrates receded by five meters (5.5 yards), which led to water shortages affecting 5.5 million people in Aleppo, Raqqa, and Deir Ezzor Governorates.

The receding Euphrates has threatened the operation and integrity of dams in Syria itself. As Syria’s reservoirs receded to nearly their dead storage capacity (meaning the volume of water in the reservoir that is below all outlets and spillways and can only be released if the walls of the dam burst), the remaining water quality was compromised, along with the ability to generate the hydropower needed to meet 70 percent of the nation’s electricity consumption needs. During the 2020–2022 drought, Lake Assad, the Tabqa Dam’s reservoir, came within 1 meter (1.1 yards) of its dead storage capacity, threatening damage to the turbines and internal flooding. Should the turbines or dam sustain damage, it would result not only in the dam’s full shutdown but also in the necessity of repairs that are beyond the capacity of local technical teams to undertake, as well as the purchase of parts they would have great difficulty in procuring. In March 2023, the Tishreen Dam was forced to suspend operations—not for the first time—due to the low level of water in the Euphrates, cutting off electricity to some 7 million people.

Two additional noteworthy examples of Türkiye meeting its own water needs and adversely affecting the situation downstream have to do with the Khabur and Balikh tributaries, which originate in Türkiye and then flow through northeastern Syria, where they connect with the Euphrates. Upstream development and dam construction in Türkiye have resulted in the drying up of the Khabur, initially in the summer but recently year-round. Syria has two dams located along the Khabur (the East and West Dams in the northeast) and both are dry. Being politically weak, the Syrian regime simply accepted this situation as a fait accompli and focused all its attention on securing water from the main branch of the Euphrates.

Similar developments in Türkiye have dried up the Balikh. Today, the Balikh receives mostly runoff from the agricultural region in Türkiye’s cities of Urfa and Harran and wastewater from nearby cities. (Wastewater and irrigation water also enter the Balikh from inside Syria.) As a result, the Balikh carries highly polluted water to the Euphrates. During droughts and severe water shortages, the Balikh’s water can make up a significant portion of the Euphrates’ flow.

As the flow of the Euphrates has declined, Syrian farmers have come to rely on well water to irrigate crops. Yet repeated droughts and mismanagement have reduced the recharge capacity of Syria’s groundwater. Ever-declining water tables and high energy prices have meant that many farmers are unable to rely on well water for irrigation. Consequently, the ability of ordinary Syrians to meet their water and food security needs remains uncertain.

The Way Ahead: Adapting to Climate Change

To build resilience to climatic vicissitudes, it is necessary to prepare infrastructure, society, farmers, and institutions for droughts and other events, along with establishing a response and recovery plan. Through such adaptation measures, the damage to civilians, the domestic economy, and the environment can be minimized. To achieve these goals, international humanitarian organizations and domestic political institutions need to adopt “no-regret measures,” which are policies that are effective regardless of the severity of climate change in the short or long term. Although the Syrian government has manipulated humanitarian aid by channeling it to its political supporters and away from its enemies, focusing on no-regret measures can mitigate the effects of corruption. Since droughts, climate change, and conflict are devastating Syria’s food, water, and energy security, building resilience is crucial for Syrians to have a viable future.

Humanitarian organizations along with government institutions should invest in the green reconstruction of water infrastructure, irrigation systems, wastewater treatment facilities, and the energy grid, all the while taking into account the impact of climate change. For instance, were Syria’s water-pumping stations to be reconstructed and relocated closer to the banks of the receding Euphrates, this would allow them to operate even in times of drought. It is also essential to repair or upgrade the turbines in Syria’s dams. Doing so would enable millions of people to receive reliable access to electricity and grant 5.4 million people access to water. Additionally, subsidies and parts should be provided to farmers to repair their equipment, so that efficiency and productivity increase, along with their farms’ ability to withstand climate change.

Another important, no-regret measure is monitoring all meteorological hazards, distributing the weather forecast for free to local communities, and establishing an early-warning system for any upcoming droughts. Humanitarian organizations and domestic political institutions must also prepare contingency plans for pre- and post-drought assistance to protect the most vulnerable segments of the population. When it comes to farmers, this plan should consider early distribution of free or highly subsidized high-quality seeds, fertilizers, and pesticides, along with energy subsidies.

Depending on the severity of the next drought and the financial situation of ordinary Syrians, a policy of climate-dependent cash transfers to help poor families cover the rising cost of food, energy, and water needs to be formulated. In order to minimize corruption, which is often rampant in conflict-affected areas, all subsidies and other forms of support should go to poor families directly. To reduce food insecurity at the household level during a drought, Syrians across the country should be given free vegetable seeds to grow their own household vegetable gardens. This measure would improve the nutritional intake of families by diversifying their diet.

Because conflict-affected states suffer from brain drain and must grapple with a shortage of technicians, the Syrian government and humanitarian organizations should launch training programs for farmers. The programs should educate them about the impact of climate change and teach them how to reduce the risk of crop failure, particularly in arid and semi-arid areas. Specifically, the programs should focus on water conservation methods, tilling techniques that allow the soil to retain moisture, water-harvesting practices, and drip irrigation technology.

Also, given that waterborne diseases in Syria are a byproduct of a lack of knowledge about how to secure safe water, an education campaign about water quality should be undertaken. To overcome the significant shortage of relevant data, humanitarian organizations could establish a water institute to research and learn from the best practices on water policies identified domestically. This knowledge would then be disseminated among farmers.

Finally, given the impact of water and energy insecurity on human security, it is essential that the international community persuade Türkiye to comply with its international commitments under the 1987 protocol. In doing so, Türkiye would contribute to minimizing the humanitarian crisis and help to support the building of a stable future state in Syria. Türkiye already hosts 3.6 million Syrian refugees and is keen to prevent any future inflows. Access to safe and sufficient water, food, and electricity in their country, along with physical safety and employment, would mean that fewer Syrians seek refuge in Türkiye and may encourage some of those who left to return. As a result, Türkiye has a national interest in stabilizing the human security of its downstream neighbor and complying with the 1987 protocol.

Conclusion

Given twelve years of protracted war and devastation, Syrian civilians are extremely vulnerable to the impact of climate change and drought. Poverty, weak government institutions, economic crises, and inflation have hampered their capacity to adapt and created a dire situation. In 2023, more than 13 million people desperately needed access to safe water and sanitation systems, along with assistance in securing hygiene products. People continue to slide deeper into poverty, threatening the human security of children, women, and the elderly. With malnutrition and hunger stunting the growth of 25–28 percent of children, the country’s future human capital is at risk. Humanitarian organizations, donors, and the government of Syria must combine efforts to build resilience to climate change and droughts with green reconstruction. Otherwise, Syrians will continue to suffer, and people will resort to any means to escape the suffering.

Water Injustice and Transboundary River Basins: Perspectives From the Occupied Golan Heights

Introduction

Around the world, 263 river basins and approximately 300 aquifers cross political borders. More than 140 countries rely on these transboundary water systems, providing rich context for policy analysts and academics to explore the ideal approach to transboundary water governance. Yet most analysts have focused their efforts on interstate transboundary relations and management, with an emphasis on negotiations, diplomacy, and infrastructure development. Issues of colonial legacy, indigenous water rights, and gender inclusion continue to be overlooked in dominant water governance mechanisms. The Jordan River Basin—where a complex, overexploited, and unequally divided river basin faces a high degree of climate vulnerability—is a case in point. While most scholars and policymakers focus on international law and riparian countries’ water exploitation in the basin, this analysis examines these conditions as they are experienced by the communities left grappling with political and ecological marginalization.

This chapter aims to expose the following: First, the limitations of existing mainstream transboundary water governance framings and global mechanisms end up reenforcing the dispossession of stateless communities such as the Jawlanis, a community of Indigenous Syrians in the occupied Golan Heights. Second, the strategies used by groups like the Jawlanis to counter domination and adapt to these compounded political and climatic realities offer pathways to transform the status quo vis-à-vis land and water management. Finally, in the context of climate change, Israel wields power by promoting renewable energies in occupied lands, continuing unabated its grip over resources and territories through a narrative of green development that relies on depoliticization and technological advancements in the Golan Heights.

Mediators and observers in transboundary river basins must pay attention to how stateless communities, like those living in the Golan Heights, have adapted to these political, geographic, and climatic changes. With an increasing number of basin inhabitants seeking refuge in neighboring countries, such as Jordan, paying attention to injustices they face when it comes to attaining their water rights is paramount. Therein lie important lessons to advance more equitable and fair policymaking on transboundary water governance.

The Jordan River Basin and the Limitations of Transboundary Framings

The Jordan River Basin presents a dynamic set of variables that has attracted academic scholarship, policymaking reports, and international relations experts, particularly regarding issues of interstate cooperation, conflict, and the allocation of flows. The Jordan River Basin is particularly unique because one of the riparian countries, the state of Israel, is an occupying power that uses a range of strategies and tools to exercise its dominance over Arab territories—including the overexploitation of shared water resources. Since its military occupation of neighboring countries’ lands in the 1967 Arab-Israeli War, Israel has enhanced its geostrategic position by maintaining a tight grip over the tributaries of the Jordan River Basin. Through bilateral arrangements, it has resulted in an unjust agreement for Jordan that extends Israeli influence over the utilization of the Yarmouk tributary in addition to the upper tributaries of the Jordan River. As an occupying power, Israel has been systematically denying basic water rights to its marginalized communities (Palestinians and Syrians) while exploiting the shared resources of other riparian countries (Syria, Lebanon, and Jordan). This, in addition to other examples of unilateral water exploitation by the Israeli state, has precluded the possibility of sound river basin management that would actually benefit local communities.

Transboundary water arrangements in the Jordan River Basin—namely the 1987 agreement between Syria and Jordan and the 1994 agreement between Israel and Jordan—and the resulting infrastructure have actually impeded progress toward a more equitable and fairer share of the river basin waters. (Allegedly, U.S.-brokered negotiations between Israel and Syria in 2000 fell apart over Israel’s refusal to recognize the pre-1967 borders, which would have returned access to Lake Tiberias in the south of the occupied Golan Heights, and thus riparian rights to the lake’s water, to Syria.) But while transboundary water governance norms, regulations, and laws may be useful and relevant to nation states and their civilian populations, they remain inadequate to address the existential challenges of communities living in protracted conflicts and under military rule. The Indigenous Jawlani community in the occupied Golan Heights provides an illustrative example of a community that has been adapting to transformative water and political realities.

The Golan Heights, a high, volcanic plateau located at the convergence of borders between Israel, Syria, and Jordan, is a strategic location with immense geopolitical and hydropolitical significance. It is a particularly water-rich area, with the highest level of rainfall in the region. The plateau annually receives between 1,000 millimeters in the north and 1,600 millimeters at Mount Hermon, while the central area receives an average of 800 millimeters and the south receives 500 millimeters. Since 1967, when Israeli forces occupied the Syrian Golan Heights, Israel has further solidified its control over the headwaters of the Jordan River, in addition to controlling the groundwater of the Palestinian West Bank. Israel’s occupation also made it an upstream riparian nation, while relegating Syria to a “no-stream” position. A thriving community of more than 140,000 people in 1966, only 5 percent of the Golan’s population—with control over just 5 percent of the occupied lands—remained after 1967. Out of two cities, 163 villages, and 108 farms, only six villages survived. The rest were completely destroyed. The Jawlanis, who today amount to about 27,000 people, have rejected ensuing attempts to enforce Israeli citizenship. In 1982, Israel declared a de facto—and, in the eyes of the international community, illegal—unilateral annexation of the Golan Heights, sparking riots and a six-month strike by the Jawlani population. The international community’s stance remains clear regarding the illegality of the Israeli occupation, aside from former U.S. president Donald Trump’s decision to recognize Israel’s sovereignty over the occupied Golan.

The Israeli state has invested heavily in exploiting water resources in the Golan Heights, constructing artificial lakes, dams, and reservoirs to harness water for the exclusive benefit of Jewish Israeli settlements, which today amount to thirty-four illegal settlements with 26,250 inhabitants. Settlements had access to land and water to grow crops, breed animals, cultivate vineyards, and attract tourism. The state, alongside settlement water companies, began drilling groundwater wells, which were very limited before 1967. Today, these wells produce around 10 million cubic meters of water per year, exclusively used by the settlements. Since the Water Law of 1959, only the Israeli state is allowed to excavate for groundwater—without express permission from the state, no groundwater wells are permitted.