Summary

The creation of global markets unleashed powerful forces—known collectively as geoeconomics—that have led to huge challenges of adjustment to new technologies, patterns of production, and modes of communication. Policymakers must address these challenges with limited resources. To meet their political objectives in this area, national governments use their control over market and nonmarket instruments—or economic statecraft.

The concept of economic statecraft therefore relates to the ways in which states connect economic tools to foreign policy goals. Meanwhile, geopolitics is about the ways in which geography and economics influence politics and interstate relations. Economic statecraft can thus be seen as a response to geopolitics that uses economic means for foreign policy ends. In a historical context, economic statecraft reflects a shift away from a neoliberal doctrine toward more interventionism in the economy.

For decades, the general consensus was that in the international policies of the European Union (EU), commercial interests prevailed over wider foreign policy strategy. In a major shift, EU institutions and European leaders now claim that this stance no longer holds. The EU has gradually moved toward a new economic statecraft that is more infused with geopolitical aims and considerations. EU member states have converged on a shared assessment that the weaponization of interdependence requires jettisoning the neat distinction between economic and security affairs. The emerging European economic statecraft encompasses a wide range of measures: Some aim to establish a level playing field with competitors, while others pursue broader external agendas, such as environmental sustainability or human rights.

The EU’s new statecraft is not only defensive but also contains offensive measures against other powers. Some of these powers complain that many new EU measures are a risk to the liberal order that the union claims to defend as its long-term strategic interest. Increasingly, the EU’s narrative is about making interdependence safe for the EU rather than the wider political-strategic aim of mutually beneficial global reforms. A backlash from other states risks deepening the strategic problems that the economic security approach is designed to address.

That is why economic statecraft in a volatile and fast-changing world is, to some extent, experimental. An excessive focus on economic security risks generating harmful unintended consequences. To move forward effectively with this agenda, the EU needs to define the larger goals that economic statecraft is supposed to serve, assess the political and strategic externalities of different policies, and tackle the trade-offs between competing priorities. This is the task for EU institutions and member states in the years ahead.

In a conflict-prone postneoliberal world, these developments require a new examination of the global ambitions and strategies of the EU—traditionally a weak foreign policy player but a strong economic actor. As a pillar of multilateralism, the EU has contributed to and benefited from the rules-based order that is now being challenged. If the EU wants to play a role in this emerging landscape, it needs to adapt its political economic model and craft an external policy fit for purpose.

Adapting to the emerging international environment may mean altering policies and approaches that have been carefully embedded in a set of liberal norms. Building greater European strategic autonomy and internal resilience may entail a shift away from these norms, raising questions about the EU’s global standing. Such a shift would also require far greater coherence between the union’s internal and external policies.

Internally, the search for a new paradigm for the EU’s political economy is challenging, as it represents a departure from the rules-based principles of multilateralism. The compromise found in the notion of open strategic autonomy leaves much room for ambiguity, discretion, and problems of definition. The EU will need to craft an industrial strategy that strikes the right balance between the bloc’s aspiration to support key industries and the imperative to maintain fair competition in the single market.

Externally, the EU will need to navigate the complexities of ensuring that its economic statecraft remains as compatible as possible with the bloc’s commitments to multilateral rules. As the traditional champion of a liberal, rules-based regime, the EU has a special responsibility to protect global multilateralism.

The success of the EU’s policy agenda will thus depend on the union’s ability to pursue its interests while upholding global rules. Although the EU may see its economic statecraft as necessary to fulfill the bloc’s ambition of economic resilience, globally there are concerns about the potential unintended effects of this approach. The external implications of the EU’s burgeoning economic statecraft will require the union to engage in diplomacy to mitigate the impacts of its domestic measures on the multilateral order.

Meanwhile, finding the right balance between economic security and broader foreign policy goals will be crucial for the EU to maintain credibility and legitimacy on the global stage. The union should therefore foster an international engagement strategy to make its practice of economic statecraft compatible with the broader development concerns of the rest of the world.

The EU should, in essence, relearn the art of the strategic management of interdependence. The union should seek to be both strategic and open. Ultimately, the EU’s ability to address the challenges of global turmoil, shifting political realities, and the demands of its member states will determine its future trajectory in a rapidly evolving world.

Introduction

European integration reached its peak in the 1990s. The European single market deepened economic interdependence on the continent. The attractiveness of that market made the European Union (EU) a global partner in bilateral and regional trade deals. The end of the Cold War enabled the EU’s enlargement to Northern and then Central Europe. And, by leveraging Europe’s interdependence and with strong public support, the EU made its first steps in foreign and security policy.

At that time, economics served the broad geopolitical goal of supporting the post–Cold War order in Europe—just as it had supported the post–World War II order. After the fall of the Berlin Wall, projecting the European model worldwide became the external corollary to the EU’s internal success: The prevailing liberal, rules-based approach to international economic relations helped defuse tensions and regulate global politics.

Thirty years later, the EU’s strength has turned into a liability. There is now a drive toward a politicization of the international economy, while rising geopolitical tensions impact on economics, security, and technology at a time when European countries are transitioning toward a green and digital economy. Rather than a conduit for cooperation, economic interdependence has become subjected to weaponization. Together, several factors are challenging the world in which European integration was possible: the unraveling of the neoliberal order, the “fuzzy bifurcation” between globalization and geopolitics (according to political scientist Richard Higgott), war in Europe and the Middle East, and the simultaneous trends of accelerated technological change and the climate crisis.

The EU’s Political Economic Model Under Threat

War in Europe and great-power rivalry are laying bare the weaknesses of the EU’s political economic model and imposing harsh choices on states. Multilateral institutions, unable to accommodate emerging demands for reform, stand by as international norms and rules are belittled, ignored, or politicized. This situation has polarizing effects on global public opinion and leaves the international order contested by both revisionist states and political actors in societies.

In a conflict-prone postneoliberal world, these developments require a new examination of the global ambitions and strategies of the EU—traditionally a weak foreign policy player but a forceful economic actor. As an experiment and a pillar of multilateralism, the EU has contributed to and benefited from the rules-based order that is now being challenged. If the EU wants to play a role in this emerging landscape, it needs to adapt its political economic model and craft an external policy fit for purpose. The task is even more daunting than it sounds, as it goes to the heart of the logic behind European integration.

Adapting to the emerging international environment may mean changing policies and approaches that have so far been carefully embedded in a set of liberal norms. Building greater European strategic autonomy and internal resilience may entail a shift away from these norms, raising questions about the EU’s global standing. Such a shift would also require far greater coherence between the union’s internal and external policies.

The double shock of the coronavirus pandemic and Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine accelerated a preexisting trend of successive EU measures in response to hostile geopolitics. The prevailing narrative about the EU’s adaptation to global disorder frames the challenge as a choice between interdependence, on the one hand, and strategic autonomy or European sovereignty, on the other. There has been much lively debate and many policy discussions about this narrative.

Running through the speeches of Europe’s political leaders and the policy documents of the EU institutions is a novel connection between security and economics, both at home and abroad. French President Emmanuel Macron, by far the union’s most intellectually engaged political leader, has spoken of a new “prosperity pact” to underpin Europe’s quest for sovereignty. Inspired by French essayist Paul Valéry’s remark at the end of World War I about the mortality of civilizations, Macron has pointed out the urgency of the endeavor, noting that because of “war and peace on our continent,” Europe can die. Launching his September 2024 report on the future of European competitiveness, former European Central Bank president Mario Draghi, too, commented on Europe’s “slow agony” should it not address its problems.

The strategic agenda of the EU’s incoming leadership for 2024–2029 sets out a framework to connect an upgrade of the single market to the EU’s ability to respond to geopolitical turmoil. A string of reports that have been published—including those by Draghi, former Italian prime minister Enrico Letta, and former Finnish president Sauli Niinistö—all address aspects of these issues.

In this context, this compilation is an inquiry into how the EU is adapting to the transformation of the international order. To address this overarching question, the chapters examine the challenges and dilemmas in a series of thematic areas where economic policy and foreign policy meet.

Economic Means for Foreign Policy Ends

The concept of economic statecraft relates to the ways in which states link economic tools to foreign policy goals. Meanwhile, geopolitics is about the ways in which geography and economics influence politics and the relations between nations. Economic statecraft can thus be seen as a response to geopolitics that uses economic means for foreign policy ends. In a historical context, economic statecraft reflects a shift away from a neoliberal doctrine and globalized economic relations toward more interventionism in the economy.

Prevalent debates frame the challenge within a binary understanding of autonomy versus interdependence. This compilation favors a multidimensional approach that simultaneously examines the politics of the EU and its external impacts. For Europe, having the political leadership to pursue economic statecraft means addressing questions of European unity, the balance between supranational and national powers, and the enduring risk of fragmentation. The interventionism required to strengthen the EU’s economic statecraft raises questions about the degree to which member states are willing to cooperate through EU institutions—or, conversely, the extent to which they will resist this creeping statecraft.

In the context of great-power rivalry, Erik Jones observes in the next chapter that the global economy is characterized by a competitive search for policy autonomy, in which governments look for instruments they can use to either take advantage of or push back against the need for change. For the EU, aside from its unfulfilled ambition of greater European sovereignty, there are inevitable questions about its preferred international relationships. How far will the EU tilt toward the United States and invest in the transatlantic partnership, and what room for maneuver might Europe have in its relations with China? Which preferred modes of interaction will the EU invest in: bilateral, minilateral, plurilateral, or multilateral? What normative and practical coherence is there between the EU’s internal and external policies? And, more broadly, to what extent can the EU shape the external environment and craft its own strategy, rather than respond defensively to hostile outside trends?

The following chapters in this compilation use this framework to examine how the EU is responding to the challenges to its political economic model. The compilation begins with a historical examination of the critical junctures at which the global economy has shifted into new political orders. As well as identifying the features of great historical transformation, Jones argues that the global economy is unlikely to survive the current competitive search for greater autonomy. Yet, today’s national politics place value on the pursuit of autonomy, making this quest conflictual in and of itself.

This is the background against which the EU’s economic statecraft needs to be placed. While policymakers recognize the salience of the connection between economics and security, crafting a mix of economic, foreign, and security policies is harder to achieve. As Giovanni Grevi and Richard Youngs show, European political rhetoric often emphasizes a sense of victimhood in the face of a dangerous international environment, justifying a resort to defensive measures to protect the European economy. Indeed, the EU risks too strong a focus on such a defensive agenda at the expense of a more proactive approach geared toward multilateral cooperation and the protection of international public goods.

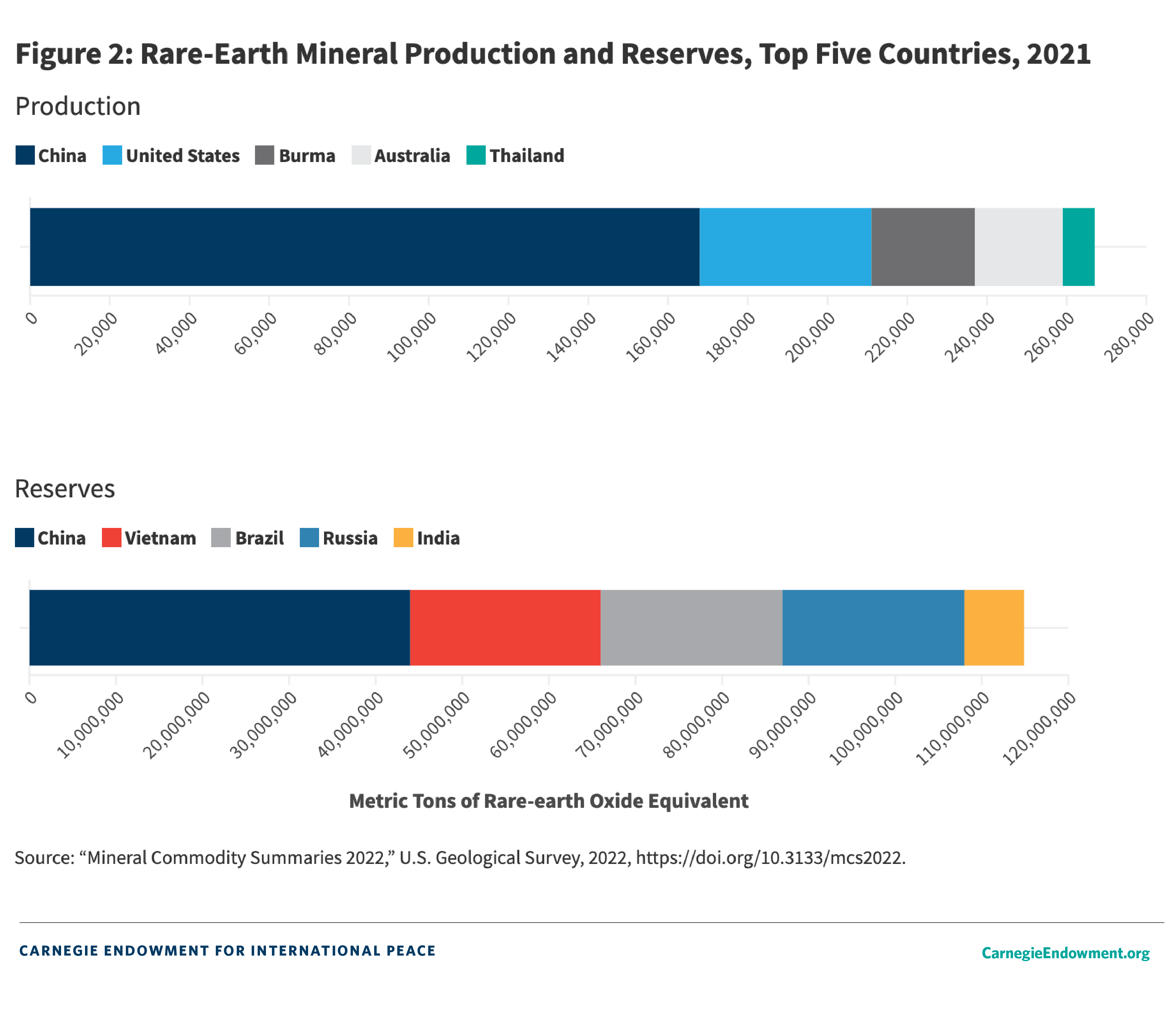

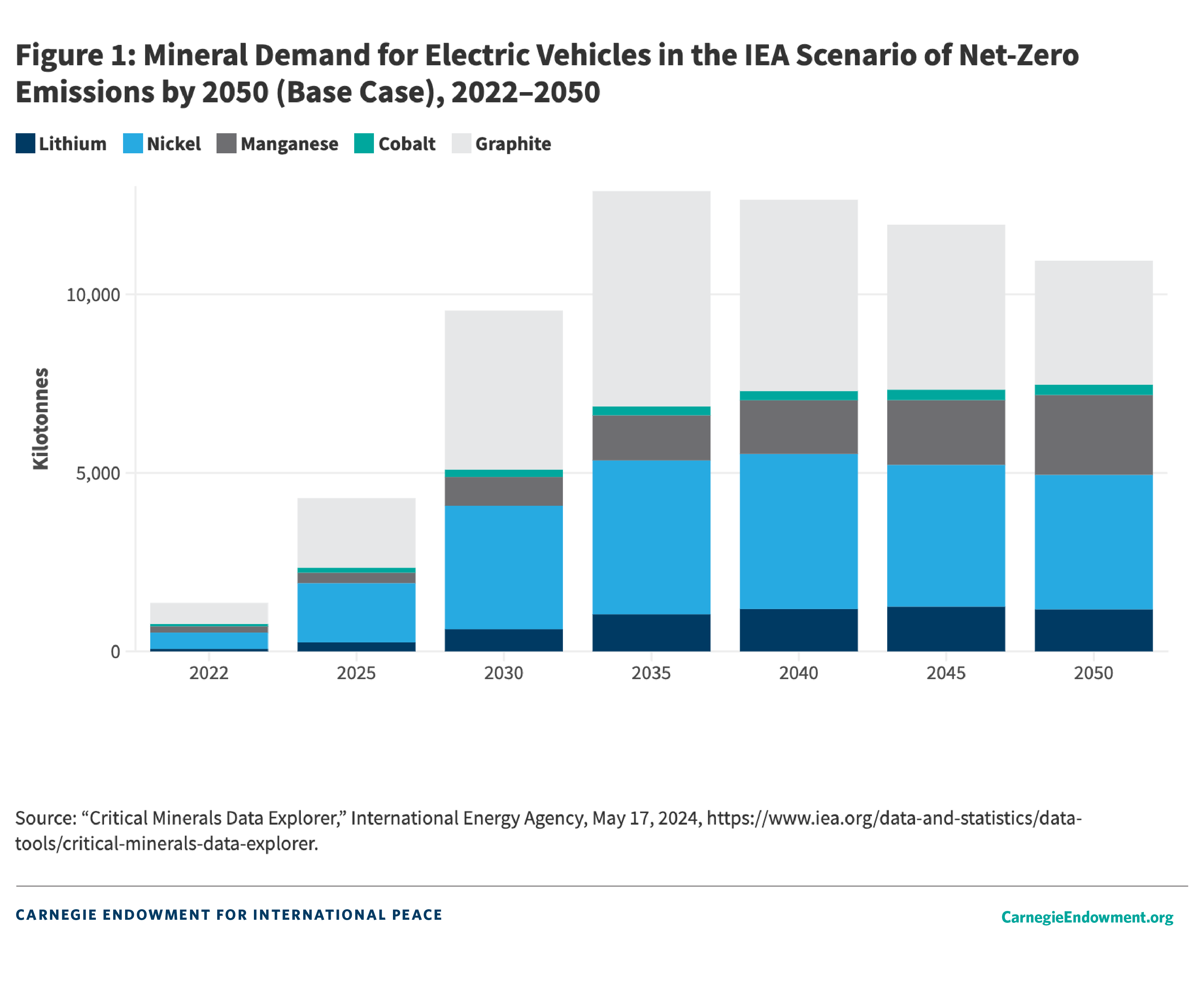

The themes explored in this compilation are broad but substantiated by specific policy analyses. Eugenia Baroncelli and Sinan Ülgen examine a range of environmental, technological, trade, and investment policies through the prism of the new doctrine of open strategic autonomy. Lizza Bomassi and Pavi Prakash Nair present supply chain resilience as the key to understanding how the EU translates its ambitions into reality with its partners. Andreas Goldthau looks at the climate agenda through the race for clean transition materials. Raluca Csernatoni considers the EU’s quest for technological sovereignty as the framing for the evolving regulation of emerging digital technologies, artificial intelligence, and the security-technology nexus. And Catherine Hoeffler analyzes security through the EU’s role in defense-industrial policy.

All of the chapters trace recent policy developments with the goal of understanding the logics and narratives of the EU’s policy choices, the degree of continuity with the union’s past practices, the policy dilemmas and possible trade-offs, and the political consensus that may—or may not—emerge to enable the union to move forward in its economic statecraft.

Internal-External Tensions

All areas of foreign policy entail an interface between internal cohesion and external projection. For the EU, these areas require a new political consensus on key choices: between openness to the world and inward-looking protectionism, and between the existing rules of international cooperation and the search for a more restrictively defined European interest. Recent policy developments also pose questions about how the EU wants to position itself in relation to other actors—allies, rivals, new partners, and, especially, the United States—and the principle of multilateralism.

At the more mundane level of policy, the EU’s dilemmas feed into specific challenges about policy preferences and diplomatic tactics. For instance, protecting and enhancing strategic assets can collide with competition and trade policies. Meanwhile, climate transition goals might be achieved by exploiting the resources of third countries, which would go against the stated goals of the EU’s global partnerships. Europe’s task is to strengthen its autonomy while working with partners bilaterally and multilaterally toward reforming global governance.

All of the chapters in this compilation provide policy-specific insights and illuminate broader trends. The gulf between the EU’s ambition of sovereignty and the economic reality in the areas of technology, innovation, and defense is so enormous as to call into question whether the term “sovereignty” is appropriate at all. The EU’s fragmentation is a chronic feature of these policy fields, and in technology the union’s catch-up needs are huge. Cognitive gaps among stakeholders abound, including between states and the private sector when it comes to the resilience of supply chains. Here, as in defense, there are political tensions between the European level and the national level.

The choice between defensive posturing and protection of the EU’s economic model, on the one hand, and engagement with the rest of the world, on the other, is a theme running through the chapters, which point out the contradictions between the EU’s internal push for autonomy and its stated goal of multilateralism. For example, as Goldthau underlines, there is a risk that the EU’s energy transition will lead to dependency-creating import structures. Baroncelli and Ülgen capture the internal-external contradictions in several recent initiatives. While underlining that the EU can exercise choice in pursuing its goal of open strategic autonomy, they wonder whether the union will be able to chart a coherent external policy on both the economic and the ideational front.

Identifying the next iterations of the economic and conceptual dimensions of European integration is the theme of the final chapter. Rosa Balfour focuses on the political legitimacy of the fledgling EU order and unpacks the economic, political, ideological, and international features that have lent legitimacy to European integration. Balfour asks whether the EU can find a new consensus when the norms that have underpinned integration are challenged by the external environment, political trends, and policy choices.

Rosa Balfour is the director of Carnegie Europe.

Sinan Ülgen is a senior fellow at Carnegie Europe.

A Global Perspective on Geopolitics and Economic Statecraft

Globalization did not bring about an end to the nation-state. The creation of global markets lifted hundreds of millions out of poverty and gave a handful of thousands extraordinary wealth. Along the way, globalization accelerated innovation, improved communication, gave rise to multinational enterprises and global value chains, and redistributed economic activity from West to East and from North to South. The transformative power of global markets is manifest. And, paradoxically, that is why the nation-state remains central to global politics.

Geoeconomics—the collection of powerful forces unleashed through the creation of global markets—has led to huge challenges of adjustment to new technologies, forms of communication, patterns of production, and locations of activity. Policymakers at all levels must address these challenges with limited resources. Doing so is necessarily a political task that involves deciding who should act and who stands to gain from specific policy choices, as well as who does not.1 The governments of nation-states—not multinational enterprises, international organizations, multilateral forums, nongovernmental organizations, or any other form of nonstate actor—remain the focal points for this kind of political agency. The more painful or difficult the adjustments are for a given society, the more central these states become.

Each national government faces different needs with different resources. Governments search for instruments they can use effectively to take advantage of the need for change, to push back against it, or to compensate those who lose out. Often that search focuses on the economic domain. National governments use their control over market and nonmarket instruments—or economic statecraft—to achieve their political objectives. Here, it is worth underscoring that economic statecraft is, and always has been, an expression of geopolitics and not of geoeconomics. Where state control over economic instruments is insufficient to the political task, governments are willing to deploy more coercive measures, including violence, both at home and abroad.

In extreme cases, where successive national governments cannot achieve their political objectives either by manipulating economic instruments or by using force, the state fails until some group emerges that is powerful enough to reenergize or replace it. In that sense, responding to geoeconomic forces is an existential requirement. Few, if any, national governments seek to undo the benefits that global markets make possible, and yet most, if not all, of them are determined to do whatever it takes to respond to the adjustment challenges those benefits entail—even if this comes at the expense of making global markets less efficient.

The global economy is unlikely to survive this competitive search for policy autonomy. Global markets exist by dint of political and policy coordination, not self-help. The exercise of political independence fragments global markets through the thousands of cuts inflicted by each national government and through the influence of institutional path dependence on the development of longer-term structural incompatibilities from one country to the next. Nation-states and non-state actors will continue to interact across the globe, but their interactions will be constrained by the implications of the policy choices they make.

Framing the argument as a competitive search for policy autonomy makes it easier to offer a global perspective on this dynamic. Every government that benefits from global markets wants to find a way to respond to challenges of adjustment without tearing those markets apart. The problem for each of them is that coordination cannot be neutral because any negotiation is going to pull some farther away than others from their preferred strategy for adjustment—just as any redistribution of adjustment costs is going to give rise to competing perceptions of fairness. In turn, those differences—both real and perceived—become fodder for opposition to governments in domestic politics.

Coordination across governments in support of global markets comes at a domestic political cost for all negotiating parties that cannot make a credible claim to have benefited more than they have conceded. At the same time, accepting the best alternative to a negotiated agreement is easier when the exercise of autonomy can be celebrated as a virtue in national politics. Indeed, the pursuit of policy autonomy often retains its value in national debates even when it comes at an economic cost both domestically and globally. That cost tends not only to accumulate across countries but also to reshape the possibilities for future coordination. The global economy is the victim of this political dynamic.

Sounds Familiar

There is nothing new in this diagnosis of the interaction between economic statecraft and geopolitics. Much the same argument can be found as a critique of the international economy in the interwar period in works written in the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s by, for example, John Maynard Keynes, E. H. Carr, Karl Polanyi, and Gunnar Myrdal.2 Hence, much of the intellectual and policy work of the early Cold War period focused on overcoming these dynamics by creating international organizations and other multilateral arrangements to enable market integration through common rules and the redistribution of adjustment costs. The Bretton Woods arrangement and other economic organizations created within the United Nations (UN) are one illustration; regional bodies developed in Western Europe, like the Organization for European Economic Cooperation and the various communities that preceded the European Union (EU) are another.

This process was never symmetrical across countries or even democratic. Those shortcomings were accepted as necessary. Writing in the 1970s, Charles Kindleberger argued that the only way to stabilize a global economy is for one country to be powerful and wealthy enough to help mitigate or underwrite the costs of adjusting to global markets for all the rest.3 John Gerard Ruggie added that even then, it is important for national governments to retain significant autonomy in the way they respond to the need for adjustment.4 And Robert Keohane suggested that a group of like-minded rich and powerful countries might find a formula for sharing the costs of stabilizing the global system.5 The United States played a leading role in the creation of the international economic order immediately after World War II; the Franco-German partners led the creation of what became the EU; and the transatlantic partners may be able to pick up the reins of the global economy after the period of U.S. hegemony ends.6

Of course, there would always be problems associated with the exercise of power in the context of interdependence. Some countries are more politically sensitive than others to the influence of geoeconomics or economic statecraft, even when their economic vulnerabilities are much the same.7 Worse, both geoeconomic forces and the exercise of economic statecraft create uncertainties that few policymakers can anticipate and few non-state actors can manage.8 Policymakers therefore quickly realized that all countries—even the largest and most powerful—need to work with those other governments with whom they are most closely connected economically if their governments are to achieve their domestic policy objectives.9

Inevitably, this coordination would systematically benefit some more than others, both in material terms and in terms of perceptions.10 As a result, not every government could be expected to aspire to coordinate in the use of economic policy instruments, and some might insist on going it alone. Over time, however, the example of coordination and the power of collective action would create incentives for even the most recalcitrant national governments to join multilateral arrangements.11

Meanwhile, any turbulence or conflict could be managed through improvements in the design of coordinating institutions and market regulations. Here, the European Economic Community provided an example of continual—if sometimes halting or only temporary—improvement as it moved through different exchange-rate regimes for the promotion of monetary stability and pivoted from trade liberalization through harmonized regulation to a new approach for dealing with nontariff barriers.12 The negotiation of the 1986 Single European Act, which launched the project to create a European internal market by 1992, was a success both economically and politically—and one that brought together the traditional Franco-German partners and the initially reluctant British government.13 The question at the end of the 1980s was whether other regions could follow Europe’s lead.14 That question expanded after the end of the Cold War to include the whole international system.

The global economy that emerged in the 1990s rested on these four elements: a diagnosis of the failings of the interwar economic order, a belief in the need for the collective management of interdependence, an acceptance that such collective action would never be wholly equitable, and a conviction that any resulting tensions could be managed in an overarching rules-based system. It also rested on the assumption that these elements are not only broadly applicable but also both portable and scalable—meaning that what works in Europe or across the Atlantic might serve as an inspiration elsewhere and function across the global economy.15

Within that assumption, it should be possible to transfer Western policies or regulations to other countries and expand Western institutional arrangements to accommodate new members: The two things go together insofar as policy and regulatory convergence can be a condition for institutional support, formal association, or even full membership. In turn, converging on Western policies or regulations and expanding Western institutions would make the global economy more cohesive as well as more inclusive.

What Went Wrong?

This whole setup for a global economy rested on a shared understanding of perceptions, values, institutions, and collective action that, with few exceptions, did not extend beyond the countries of North America, Western Europe, and other advanced industrial democracies—known collectively as the West. Non-Western participants did not accept the West’s diagnosis of what had gone wrong in the interwar period, not because they rejected the theory, but because they told a different historical narrative about colonialism and structural dependence.16 Within that alternative narrative, equity is more important than economic efficiency, particularly when that efficiency is put at the service of exploitative trade and financial practices. Tolerating some inequality in the service of policy coordination is a bad trade-off. Non-Western countries would rather have equitable institutions than effective ones, and they are willing to thwart collective action to force institutional change. This was the logic behind the call for a new international economic organization in the 1970s.17

Where that change did not happen, the governments of non-Western countries created their own organizations. Not all of these bodies were successful at garnering representation or exercising influence. The Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries is an important outlier. But that stands to reason: The non-Western world is more heterogeneous than the West; what unites these countries in general terms is their opposition to what they perceive to be an unjust international system. The success of non-Western countries in creating alternative arrangements is less important than the fundamental disagreement over values—equity versus efficiency—and the implications of that disagreement for the functioning of the institutions that foster collective action.

For their part, Western powers resisted the practical implications of inclusiveness. Rather than democratize institutions, these powers sought to reengineer them in ways that reinforced hierarchy and preserved privilege. When that failed, they turned against established forums for collective action and shifted to other venues, where they could exercise greater autonomy. Like their non-Western counterparts, Western governments were prone to creating new institutions when they felt they lacked control over existing ones.18 This venue shopping at least partly explains why the Group of Seven (G7) was formed in the wake of debates about a new international economic order as non-Western countries pushed to democratize UN-chartered economic institutions.19

Western powers also overestimated their ability to transpose their own lessons about policies and institutions to economies with very different institutional and political arrangements. This kind of template thinking aligned well with the need to attach conditions to requests for institutional support or membership, but it fitted poorly with the goal of improving economic performance in non-Western countries—and often triggered social unrest and political instability instead.20 Very quickly, the policy principles of the so-called Washington consensus that were supposed to frame the emergence of the global economy became a focus for conflict between the Western governments that promoted them and the non-Western governments charged with putting them into practice.21

This conflict escalated during the Asian financial crisis toward the end of the 1990s.22 Many of the newly industrializing countries in Asia liberalized their capital markets in line with Washington consensus recommendations. This effort succeeded in attracting foreign capital, which was a boon for Asian countries’ domestic industries, but it came at the cost of greater vulnerability to capital flight. Once the outflow started, it became contagious, first across the region, and then implicating other emerging markets, like Russia and Latin America.23 Asian governments lost confidence in the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank and decided instead to impose capital controls and build up foreign exchange reserves as a form of self-insurance.24 They also began to explore ways to share U.S. dollar–denominated assets across the region, rather than rely on conditional assistance from the West.

Emerging markets were not alone in struggling to adhere to consensual recommendations for best market practice. The difficulties of shifting policy or institutional blueprints across national boundaries also applied within the West.25 Western countries may be less heterogeneous than their non-Western counterparts, but they are still very different in terms of both institutional endowments and the way they perceive the trade-off between equity and efficiency.26 Importantly, such differences are not limited to the national level; often they extend down to the regional and local levels. As a result, it is necessary to identify not only the relative importance of equity and efficiency but also how much diversity different political systems can tolerate.

The virtues of market liberalization through policy convergence are a case in point. As the EU pushed the completion of its internal market, the United States went in a very different direction and allowed greater diversity at the state level in terms of taxation, benefits, public procurement, licensing, and regulation.27 These different trajectories not only complicated the negotiation of the Uruguay Round within the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade—the precursor to the World Trade Organization (WTO)—but also added considerable tension to the debate across the Atlantic about what it means to have a free market.28

These different non-Western and Western dynamics came together at the end of the 1990s in the emergence of the “no-global” protest movement and in the early to mid-2000s in the failure of the Doha Round of trade and development talks in the WTO. The no-global movement organized diverse political groups, drawn from both non-Western and Western societies and inspired by a wide array of ideological sources to challenge the exclusiveness of international economic organizations and demand greater representation for non-Western interests.29 The Doha Round was partly a response to this pressure; it included development as a major focus and engaged directly with governments in emerging markets. Quickly, however, the Doha Round morphed into an arena for debating trade liberalization requirements that would give Western governments greater influence over labor standards, environmental protection, and other regulatory practices in non-Western countries.30

When the Doha Round failed to generate a multilateral agreement, the United States and the EU shifted to bilateral trade negotiations with third countries, where they could use their relative market size and wealth to exercise greater leverage over any agreement. As with the venue shopping for multilateral cooperation, this shift from multilateral to bilateral trade negotiations was widely perceived in emerging markets as an attempt to reinforce Western privilege. That perception was not shared in either the United States or Europe. Instead, the West took a narrower view focused on the virtues of its own policies and the need to pursue national or European interests.31

Declining State Effectiveness, Increasing Politicization, and Evolving State Capacity

The deepening divisions in the global economy were apparent in the early 2000s, long before the onset of the 2007–2008 global financial crisis. The problem was the one already identified by Keynes in his 1936 General Theory.32 It is worth quoting him at length, because aside from the syntax and word choice, the argument sounds so contemporary:

Thus, while economists were accustomed to applaud the prevailing international system as furnishing the fruits of the international division of labour and harmonising at the same time the interests of different nations, there lay concealed a less benign influence; and those statesmen were moved by common sense and a correct apprehension of the true courses of events who believed that if a rich, old country were to neglect the struggle for markets its prosperity would droop and fail.

Keynes went on to argue that the only way to avoid having the international economy deteriorate into “what it is, namely, a desperate expedient to maintain employment at home by forcing sales on foreign markets and restricting purchases” was for states “to learn to provide themselves with full employment by their domestic policy.”

That insight was baked into the post–World War II economic system. At its core, the global economy depended on nation-states to smooth the process of adjustment and minimize the politicization of international coordination. As the global economy expanded to include ever more diverse countries, the necessary adjustments grew to exceed the ability or willingness of national governments. Over time, governments fell behind in their efforts to minimize adjustment costs and maintain full employment, and opposition groups took advantage of that failure to ramp up their efforts to politicize international cooperation. This discontent mingled with other complaints about advanced industrialized democracies and the elites who led them to form what political scientist Cas Mudde called a “populist Zeitgeist,” which was as opposed to the global economy as it was to elite privilege.33

This discontent fed directly into efforts to instrumentalize trade policy in contradictory ways in both Europe and the United States. In those areas where domestic interests made no complaint about the functioning of global markets, national governments pushed for liberalization and multilateral engagement. Where domestic interests expressed opposition to global markets, governments pushed the other way, using a mix of instruments like antidumping measures or social regulations to raise barriers to international exchange. Thus, borrowing from political scientists Alasdair Young and John Peterson, “the EU is both liberal and protectionist in predictable ways.”34 And the same could be said of the United States.35

Meanwhile, the efforts of emerging market economies to create a form of self-insurance by accumulating foreign exchange reserves began to create distortions across the global economy.36 Such reserves can be earned only when countries run consistent current account surpluses by exporting more goods and services than they import. This form of macroeconomic imbalance is theoretically unsustainable over the long run, but that unsustainability reveals itself in different ways from the kind of balance-of-payments crisis that arises from a lack of competitiveness. Instead of facing a progressive deterioration of the terms of trade, countries experience a sudden stop as the flow of funds on the capital account rushes out of the national economy.37 To understand why, it is necessary to focus on the way the capital account finances the current account in the balance of payments.

Foreign exchange reserves are assets denominated in foreign currency. When a government wants to accumulate foreign exchange reserves as a matter of policy, it commits to buying foreign currency–denominated assets. The net export of goods and services is just one way to raise the money for these purchases. While it is common to imagine that countries that import more than they export have to borrow money, it is more common for governments to introduce policies to ensure they export more than they import to purchase foreign assets to use as foreign exchange reserves. And since the global balance of payments must balance (by definition), these two ways of looking at the financial implications of macroeconomic balances are mirror images.

The asset purchases made by governments in emerging markets as a form of self-insurance after the Asian financial crisis represented a massive export of capital.38 This export created liquidity—or spendable money—in other countries, primarily the United States, that could be used only to buy assets or additional imports from abroad. The result was either an inflation of asset prices in the importing countries or another round of net exports and the accumulation of foreign reserves for the governments seeking this form of self-insurance. This policy was unsustainable over the long run because of the distortions it created in the asset markets of the net-importing countries—again, primarily the United States—which experienced ever-increasing prices for government bonds, real estate, stocks, and even commodities. The 2007–2008 global financial crisis started when the market for one of these asset classes collapsed.39 What followed was a series of sudden stops as cross-border investors started liquidating their assets either to repatriate their capital or to send it to a safer investment market.

This thesis of a global liquidity glut was not readily embraced among emerging market economies—and, indeed, never has been widely accepted in much of Asia—but it was adopted in the United States and Europe. The decision to shift the focus of multilateral cooperation from the G7 to the larger Group of Twenty (G20) was a consequence. Western governments, including that of the United States in particular, needed a more inclusive forum to deal with macroeconomic imbalances that they believed originated in emerging market economies.40

The fact that those economies embraced macroeconomic imbalances to generate foreign exchange reserves that they could use to avoid having to rely on Western institutions like the IMF closed the circle.41 The economic institutions created after World War II had failed to represent the interests of emerging market economies. The governments of these economies turned away from these institutions and, in doing so, created market distortions at the global level. And when these distortions resulted in the global financial crisis, Western governments shifted their attention to more inclusive institutions to convince the governments of emerging markets that had created those distortions to help get them under control.42

The implication of this story is that the creation of the global economy gave the governments of emerging market economies access to geopolitical power that Western governments could not ignore. That power included the ability not only to distort world markets but also to ignore, manipulate, or duplicate the institutions created to foster international economic cooperation. If Western governments alternated between liberalization and protectionism, governments in emerging markets could challenge the more protectionist efforts at the WTO. More importantly, they had the power to exercise leverage through and over the WTO’s dispute resolution mechanism.43

Non-Western governments were not the only ones who were empowered by the creation of a global economy. Western governments acquired new powers related to the central role they played in the development of the three basic infrastructures that underpin global markets: currency, finance, and telecommunications.44 Global transactions need a common denominator to set prices, store value, and make payments; they need credit, insurance, clearing, settlement, and somewhere to keep things safe; and they need some way to interact at a distance to communicate detailed information unambiguously and with a clear record of what was said, whether the message was received, and whether it was acted on.

These infrastructures are challenging enough to develop around the exchange of finished products, and the first truly global form of capitalism took many hundreds of years to emerge.45 This is hardly surprising: Even for the most basic trade, the currency needs to be widely accepted, the finance flexible and stable, and the means of communication reliable and secure. Hence, the focus for commerce was on human relationships and personal interaction. The task became more difficult in the exchange of intermediate goods as part of distributed manufacturing processes. Then it became necessary to work more with numbers than with people and to trust technology more than personal relationships.46 With the introduction of global value chains and the emergence of the internet, the endeavor reached new magnitudes of complexity.47 And, for historical reasons, Western countries were at the center of that infrastructural revolution.

This central location gave Western governments two largely unexpected forms of power: One was to oversee the transactions that make up the global economy, and the other was to prevent them from happening.48 The United States has taken advantage of its central role in the world economy—and, specifically, the central role of the U.S. dollar—at least since World War II.49 The U.S. Treasury created the first entity responsible for monitoring dollar-denominated payments in 1940, renamed the Office of Foreign Assets Control in 1950. But it was only after the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001, that the U.S. government realized the full extent of its ability to sift through the internet and the record of interbank transactions to track terrorist financing and restrict access to the U.S. financial system.

The first administration of former U.S. president Barack Obama used this control to compel Iran to engage in negotiations over its nuclear program. It did so by preventing Iranian banks from participating in dollar-denominated clearing and forcing the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (SWIFT) to disconnect Iranian banks from the global network for interbank telecommunications. The second Obama administration joined the EU in using many of the same instruments against Russia after its 2014 annexation of Crimea, cutting Russia off from access to European and U.S. capital markets.50 The transatlantic partners went even further in putting pressure on Russia after its 2022 full-scale invasion of Ukraine.51 These new instruments of economic statecraft were unbelievably powerful. They also proved to be a wasting asset.

Economics, Security, and Strategic Autonomy

The problem with weaponizing interdependence—the process by which states leverage global networks of informational and financial exchange for strategic advantage—is that it encourages governments everywhere to disengage from institutionalized cooperation and find ways to reduce their vulnerability to economic integration.52 If the lesson for the countries of East and Southeast Asia at the end of the 1990s was about the importance of self-insurance, even if that creates global market distortions, the lesson from the 2010s for governments everywhere was about the importance of economic security and strategic autonomy. And that lesson applied within the West as well as between Western and non-Western countries.53

This point is worth underscoring and putting into historical context. The use of economic sanctions did not start the shift away from neoliberal forms of market competition. The turn to economic statecraft and related nonmarket forms of state intervention, like industrial policy, began long before the coronavirus pandemic or the 2022 invasion of Ukraine. The EU started turning away from neoliberal free-market ideology even before the global financial crisis.54 By that time, the first administration of former U.S. president George W. Bush had already demonstrated its willingness to use tariffs to restore the competitiveness of the U.S. steel and agricultural sectors.55

This shift toward more nonmarket interventions accelerated during the global financial crisis as governments everywhere sought to bail out strategic industries and banks. And it continued to develop as the rise of U.S. technology companies and Chinese manufacturing industries underscored the changing nature of the global economy. Donald Trump’s 2016 presidential campaign was a symptom, not a cause, of this transformation. When Trump was elected and his incoming administration made clear the transactional nature of his presidency, Europe’s response was to begin planning an even more interventionist shift in its approach to the use of industrial policy instruments and the politicization of trade policy.56

The end of the 2010s was a fertile period for the development of new approaches to economic policymaking—both foreign and domestic—on both sides of the Atlantic. In the United States, Democrats hoping to return to office forged what Carnegie’s Salman Ahmed and Rozlyn Engel called a “foreign policy for the middle class,” which would blur the lines between economic and foreign policies to use the same instruments to achieve multiple objectives: income distribution and manufacturing competitiveness at home, and military security and supply chain resilience abroad.57 European officials were also looking for ways to strengthen the EU’s strategic autonomy in terms of both technological innovation and military procurement.58

What the use of sanctions did was deepen the friction and suspicion already being created by the breakdown of the Washington consensus and the shift away from neoliberalism. When the Obama administration cut Iran out of SWIFT in 2012, it had to push hard to get Europeans to go along because they feared that this weaponization of a global financial cooperative, headquartered in Belgium, would set a bad precedent in the eyes of the wider world.59 When the United States and the EU cut Russian firms out of Western capital markets in 2014, the Chinese and others were quick to take note of the wider implications for their own reliance on the dollar and the euro.60 And when the Trump administration announced in 2018 that it would pull out of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), which lifted sanctions on Iran in exchange for restrictions on the country’s nuclear facilities, and instead threatened secondary sanctions on European firms that refused to comply with this change in U.S. policy, the EU began planning its own legal instrument to push back against such economic coercion.61

The experience of the coronavirus pandemic reinforced this dynamic by revealing both the fragility of global supply chains and the reflexive nature of economic nationalism, and not just in Europe and the United States. Although EU member states may have been surprised by the sudden fights that broke out over personal protective equipment and respirators, the European Commission was quick to swing into action and the European Council found new ways to strengthen European solidarity.62 The same was not true of relations between Europe, the United States, and the rest of the world. Non-Western countries experienced severe shortages of basic personal protective equipment and lacked the necessary tools to shut down their economies to slow the spread of the virus. These countries faced even greater difficulties getting access to vaccines once they became available. The pandemic put the self-serving and transactional nature of the global economy on full display.63

The Western response to Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine only reinforced the contrast. The United States and the EU quickly rolled out unprecedented sanctions against the Russian government and economy in response to Russia’s unprovoked and unjustifiable aggression.64 Once again, this move demonstrated the vulnerability of any country to key forms of interdependence with lead actors in the global economy. It also provoked a series of unintended disruptions to supply chains, food distribution, energy prices, and transportation routes, with serious negative consequences for other parts of the global economy. For many non-Western governments, the costs of trying to contain the Russian aggression appeared disproportionate when compared with efforts to address violent conflict elsewhere.65

The sanctions against Russia proved less effective than many in the West had imagined.66 This outcome raises the question of whether the Russian government may have used the time between its 2014 annexation of Crimea and its 2022 invasion of Ukraine to limit its vulnerability to Western leverage.67 This situation may also strengthen the regime’s authoritarian character to limit domestic political sensitivity to the costs of disengaging from the West. Such concerns are worth noting because they underscore the waning effectiveness of weaponized interdependence.68 They also suggest that China may already be prepared to push back against the West. Weaning the Chinese economy off dependence on U.S. dollar–denominated assets and transactions may not yet be realistic, nor may reducing China’s dependence on U.S. markets and advanced technology.69 But the Chinese government can make its economy more resilient in the face of U.S. pressure and rally its population against U.S. economic coercion in ways that will only diminish popular support for the Western-led rules-based international system.

Putting It All Together and Longer-Term Implications

The administration of U.S. President Joe Biden was probably right that the only effective way to build political support for an open U.S. economy is to ensure that such an economy benefits the middle class. For its part, the EU is probably right to aspire to strengthen its strategic autonomy both in general terms and with particular reference to the United States. No U.S. administration can take popular support for American global leadership for granted, and no EU official should expect to count automatically on support from the United States. The bonds that hold the West together as a global political construct still exist, and so do the Western institutions that structure the global economy. But the West is no longer so monolithic, and the non-Western world is no longer so eager to accept Western leadership.

Two scenarios flow from this weakening of the West, one negative and the other positive. The negative scenario is that national governments can be expected to use the instruments of economic statecraft to address different domestic agendas in a more loosely coordinated fashion within the West and largely without systematic coordination with governments elsewhere.70 This is a troubling prospect, because it leaves significant room for friction of the kind that arose across the Atlantic around the Biden administration’s 2022 Inflation Reduction Act.71 It is also troubling because it suggests that many problems that require truly global responses, like climate change, will be met with only piecemeal efforts that work to varying degrees from one national jurisdiction to the next. When the nation-state is the center of attention, that is about the best that can be hoped for. Whether it will be sufficient is an open question. Economic statecraft is no replacement for global economic leadership.

A more extreme version of this negative scenario is that the world economy will become divided into blocs that use competing standards for manufacturing and digital technology. This is a logical consequence of the ever-increasing weaponization of interdependence.72 Such a world will be neither representative nor effective. On the contrary, it will be prone to the kind of conflict that existed in the interwar period and that the creation of a global economy under Western leadership was meant to address.73 The results will not be identical to what has been experienced in the past, but they will be similar enough to be familiar.

The more positive scenario is that Western and non-Western governments find a way to come together to address these global problems in ways that are more symmetrical, inclusive, and democratic. Doing so is a question not of virtue but of necessity and resilience. The global financial crisis showed that the forces of geoeconomics are too large to be managed by the West acting alone. They are also too powerful to be ignored. The climate crisis is a good illustration, but it is only one among several.

Moreover, the costs of dismantling the global economy—higher prices, lower real incomes, greater job insecurity, and more inequitable access to resources—are simply too high for societies to bear in any part of the world. As Keynes made clear, peace is possible only when security and economics reinforce one another everywhere. By implication, the new world economy will have to win support far beyond the West if it is to be durable. And durability will be the true measure of its success.

Erik Jones is a nonresident scholar at Carnegie Europe.

Notes

1Kathleen R. McNamara, “Transforming Europe? The EU’s Industrial Policy and Geopolitical Turn,” Journal of European Public Policy 31, no. 9 (2024): 2371–2396, https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2023.2230247.

2John Maynard Keynes, The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money (London: Macmillan, 1936); E. H. Carr, The Twenty Years’ Crisis, 1919-1939 (London: Macmillan, 1981); Karl Polanyi, The Great Transformation: The Political and Economic Origins of Our Time (Boston: Beacon Press, 2001); and Gunnar Myrdal, An International Economy: Problems and Prospects (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1956).

3Charles P. Kindleberger, The World in Depression, 1929-1939 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986).

4John Gerard Ruggie, “International Regimes, Transactions, and Change: Embedded Liberalism in the Postwar Economic Order,” International Organization 36, no. 2 (1982): 379–415.

5Robert O. Keohane, After Hegemony: Cooperation and Discord in the World Political Economy (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1984).

6David P. Calleo, Beyond American Hegemony: The Future of the Western Alliance (New York: Basic Books, 1987).

7Robert O. Keohane and Joseph S. Nye, Jr., Power and Interdependence (London: Pearson, 2011).

8Susan Strange, Casino Capitalism (London: Basil Blackwell, 1986).

9Richard N. Cooper, The Economics of Interdependence: Economic Policy in the Atlantic Community (New York: McGraw Hill, 1968).

10Robert Gilpin, U.S. Power and the Multinational Corporation: The Political Economy of Foreign Direct Investment (New York: Basic Books, 1975).

11Lloyd Gruber, Ruling the World: Power Politics and the Rise of Supranational Institutions (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000).

12Daniel Gros and Niels Thygesen, European Monetary Integration: From the European Monetary System to Monetary Union (London: Longman, 1992); and Jacques Pelkmans, “The New Approach to Technical Harmonization and Standardization,” Journal of Common Market Studies 25, no. 3 (1987): 249–269.

13Nicolas Jabko, Playing the Market: A Political Strategy for Uniting Europe, 1985-2005 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2006).

14Robert O. Keohane and Stanley Hoffmann, eds., The New European Community: Decisionmaking and Institutional Change (Boulder: Westview, 1991).

15Lora Anne Viola, The Closure of the International System: How Institutions Create Political Equalities and Hierarchies (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020).

16Raúl Prebisch, “The Economic Development of Latin America and Its Principal Problems,” Economic Bulletin for Latin America 7, no. 1 (1962): 1–22; and Fernando Henrique Cardoso and Enzo Faletto, Dependency and Development in Latin America (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1979).

17Robert W. Cox, “Ideologies and the New International Economic Order: Reflections on Som Recent Literature,” International Organization 33, no. 2 (1979): 257–302.

18Gruber, Ruling the World.

19Viola, The Closure of the International System.

20Elinor Ostrom, Understanding Institutional Diversity (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005).

21John Williamson, “A Short History of the Washington Consensus,” Law and Business Review of the Americas 15, no. 1 (2009): 7–26, https://scholar.smu.edu/lbra/vol15/iss1/3.

22Paul Blustein, The Chastening: Inside the Crisis That Rocked the Global Financial System and Humbled the IMF (New York: Public Affairs, 2003).

23Richard Bookstaber, A Demon of Our Own Design: Markets, Hedge Funds, and the Perils of Financial Innovation (London: Wiley, 2008).

24Manuela Moschella, Governing Risk: The IMF and Global Financial Crises (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010).

25Nancy Cartwright and Jeremy Hardie, Evidence-Based Policy: A Practical Guide to Doing It Better (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012).

26André Sapir, “Globalization and the Reform of European Social Models,” Journal of Common Market Studies 44, no. 2 (2006): 369–390, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5965.2006.00627.x.

27Thomas Philippon, The Great Reversal: How America Gave Up on Free Markets (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2019).

28Sophie Meunier, Trading Voices: The European Union in International Commercial Negotiations (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005).

29Tony Clarke, “Taking on the WTO: Lessons From the Battle of Seattle,” Studies in Political Economy 62, no. 1 (2000): 7–16, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/19187033.2000.11675238.

30Alasdair R. Young and John Peterson, “The EU and the New Trade Politics,” Journal of European Public Policy 13, no. 6 (2006): 791–810, https://doi.org/10.1080/13501760600837104.

31Alasdair R. Young and John Peterson, Parochial Global Europe: 21st Century Trade Politics (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014).

32Keynes, The General Theory, 382.

33Cas Mudde, “The Populist Zeitgeist,” Government and Opposition 39, no. 4 (2004): 541–563, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1477-7053.2004.00135.x.

34Young and Peterson, Parochial Global Europe.

35Veronica Anghel and Erik Jones, “The Transatlantic Relationship and the Russia-Ukraine War,” Political Science Quarterly (2024), https://hdl.handle.net/1814/76987.

36Blustein, The Chastening.

37Guillermo A. Calvo, “Capital Flows and Capital Market Crises: The Simple Economics of Sudden Stops,” Journal of Applied Economics 1, no. 1 (1998): 35–54, https://doi.org/10.1080/15140326.1998.12040516.

38Blustein, The Chastening.

39Martin Wolf, Fixing Global Finance: How to Curb Financial Crises in the 21st Century (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009).

40Gordon S. Smith, “G7 to G8 to G20: Evolution in Global Governance,” Centre for International Governance Innovation, May 2011, https://www.cigionline.org/sites/default/files/g20no6-2.pdf.

41Blustein, The Chastening.

42Erik Jones, “Shifting the Focus: The New Political Economy of Global Macroeconomic Imbalances,” SAIS Review of International Affairs 29, no. 2 (2009): 61–73, https://doi.org/10.1353/sais.0.0055.

43Robert Mcdougall, “The Crisis in WTO Dispute Settlement: Fixing Birth Defects to Restore Balance,” Journal of World Trade 52, no. 6 (2018): 867–896, http://dx.doi.org/10.54648/TRAD2018038.

44Henry Farrell and Abraham L. Newman, Underground Empire: How America Weaponized the World Economy (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2023).

45Maarten Prak and Jan Luiten van Zanden, Pioneers of Capitalism: The Netherlands 1000–1800 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2022); and Michael Sonenscher, Capitalism: The Story Behind the Word (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2022).

46Quentin Bruneau, States and the Masters of Capital: Sovereign Lending, Old and New (New York: Columbia University Press, 2022).

47Gottfried Leibbrandt and Natasha de Terán, The Pay Off: How Changing the Way We Pay Changes Everything (London: Elliot & Thompson, 2021).

48Henry Farrell and Abraham L. Newman, “Weaponized Interdependence: How Global Economic Networks Shape State Coercion,” International Security 44, no. 1 (2019): 42–79, https://doi.org/10.1162/isec_a_00351.

49Calleo, Beyond American Hegemony.

50Erik Jones and Andrew Whitworth, “The Unintended Consequences of European Sanctions on Russia,” Survival 56, no. 5 (2014): 21–30, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00396338.2014.962797.

51Farrell and Newman, Underground Empire.

52Farrell and Newman, “Weaponized Interdependence.”

53Anghel and Jones, “The Transatlantic Relationship.”

54Franco Mosconi, The New European Industrial Policy: Global Competitiveness and the Manufacturing Renaissance (London: Routledge, 2015).

55Erik Jones, “Introduction,” International Affairs 80, no. 4 (2004): 587–593, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2346.2004.00405.x.

56McNamara, “Transforming Europe?”; and Sarah Bauerle Danzman and Sophie Meunier, “The EU’s Geoeconomic Turn: From Policy Laggard to Institutional Innovator,” Journal of Common Market Studies 62, no. 4 (2024): 1097–1115, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/jcms.13599.

57Salman Ahmed and Rozlyn Engel (eds.), “Making U.S. Foreign Policy Work for the Middle Class,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, September 23, 2020, https://carnegieendowment.org/research/2020/09/making-us-foreign-policy-work-better-for-the-middle-class?lang=en.

58Sebastian Heidebrecht, “From Market Liberalism to Public Intervention: Digital Sovereignty and Changing European Union Digital Single Market Governance,” Journal of Common Market Studies 62, no. 1 (2024): 205–223, https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.13488; and Daniel Fiott, “From Liberalisation to Industrial Policy: Towards a Geoeconomic Turn in the European Defence Market?,” Journal of Common Market Studies 62, no. 4 (2024): 1012–1027, https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.13600.

59Jones and Whitworth, “The Unintended Consequences.”

60Daniel McDowell, Bucking the Buck: US Financial Sanctions and the International Backlash Against the Dollar (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2023).

61Christian Freudlsperger and Sophie Meunier, “When Foreign Policy Becomes Trade Policy: The EU’s Anti-Coercion Instrument,” Journal of Common Market Studies 62, no. 4 (2024): 1063–1079, https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.13593.

62Erik Jones, “COVID-19 and the EU Economy: Try Again, Fail Better,” Survival 62, no. 4 (2020): 81–100, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00396338.2020.1792124.

63Rajiv J. Shah, “The COVID Charter: A New Development Model for a World in Crisis,” Foreign Affairs, August 24, 2021, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/africa/2021-08-24/covid-charter.

64Christine Abley, The Russia Sanctions: The Economic Response to Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2024).

65David Miliband, “The World Beyond Ukraine: The Survival of the West and the Demands of the Rest,” Foreign Affairs, April 18, 2023, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/ukraine/world-beyond-ukraine-russia-west.

66Bruce W. Jentleson, Sanctions: What Everyone Needs to Know (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2022).

67Abley, The Russia Sanctions.

68Agathe Demarais, Backfire: How Sanctions Reshape the World Against U.S. Interests (New York: Columbia University Press, 2022).

69McDowell, Bucking the Buck.

70Anghel and Jones, “The Transatlantic Relationship.”

71Bruce Stokes, “EU-US Relations After the Inflation Reduction Act, and the Challenges Ahead,” European Parliamentary Research Service, February 2024, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2024/759588/EPRS_STU(2024)759588_EN.pdf.

72Demarais, Backfire.

73Anghel and Jones, “The Transatlantic Relationship.”

Economic Statecraft and EU Strategic Interests

Economic statecraft consists of using economic means to pursue foreign policy goals.1 Rising competition and volatility on the global stage have heightened the salience of connections between economic policies, security issues, and foreign policy. The European Union (EU) insists that political-strategic considerations have begun to play a more prominent role in its external economic policies. The union started to move tentatively in this direction some years ago, and Russia’s war on Ukraine has reinforced this shift in an apparently decisive way. At least in formal terms, the EU has begun to fashion a different kind of statecraft, in which economic policies serve broader strategic goals alongside policy-specific commercial objectives. This approach represents a potentially deep-seated change, given that the EU has traditionally been seen as an overwhelmingly economic actor bereft of strong geopolitical orientations.

While the rise of a more strategically oriented EU economic statecraft is a significant change, two nuances should be noted. First, a degree of short-term and defensive mercantilism persists in EU economic policies that does not appear to be informed by strong strategic dynamics. Second, it is not yet clear how the EU’s current emphasis on economic security fits with other priorities on the union’s foreign policy agenda. Although the EU has started to frame a different approach to economic security, it still needs to conceptualize how this relates to a broader understanding of economic statecraft and to other political-strategic priorities.

Economic security is an increasingly important component of economic statecraft, but the latter covers a much wider ground. Viable economic statecraft requires a clearer definition of which European interests are to be advanced and a more coherent mix of economic and strategic policies. As the EU rightly moves away from market primacy over foreign and security policy, it risks overcorrecting toward a defensive and competitive geopolitics.

A New Economic Statecraft?

For decades, the general consensus was that in the EU’s international policies, commercial interests prevailed over wider foreign policy strategy. In a major shift, EU institutions and European leaders have come to claim that this position no longer holds. The EU has gradually moved toward a new economic statecraft that is more infused with strategic considerations and aims. EU member states have converged on a shared assessment that the weaponization of interdependence—in which states leverage global economic and information flows for strategic advantage—requires softening the divide between economic and security affairs.2

The emerging European economic statecraft encompasses a wide range of measures: Some aim to establish a level playing field with Europe’s economic competitors; others pursue broader external agendas, such as environmental sustainability; and yet others deal with the security impact of other states weaponizing interdependence.3 In this context, security-related concerns appear to be playing a growing role in shaping Europe’s fledgling economic statecraft.

The shift has occurred incrementally over the last decade and deepened in the wake of Russia’s February 2022 invasion of Ukraine. In the 2010s, the EU’s approach to and perspective on globalization shifted toward a more politically managed form of globalism. The union became increasingly concerned with mitigating economic vulnerabilities and less enthused by the abstract value of supposedly win-win multilateral rules.4 The COVID-19 pandemic extended these shifts in the EU’s external economic policy, as it added to concerns about the union’s dependence on global supply chains for medical equipment and other goods.

Into the 2020s, several new EU strategies and documents promised economic policies geared toward the defense of “Europe’s sovereignty”—implying a more political tenor to economic strategy.5 In early 2021, the European Commission placed open strategic autonomy at the core of its Trade Policy Review, defining the concept as “the EU’s ability to make its own choices and shape the world around it through unity and engagement, reflecting its strategic interests and values.”6 The notions of open strategic autonomy and European sovereignty do not fully overlap, but they share much common ground. They emphasize the need to reduce economic vulnerabilities and defend EU interests while restating the importance of multilateral cooperation and engagement.

The war on Ukraine has added to the priority that European governments attach more specifically to economic security. Most governments have interpreted the conflict as a strong vindication of the need for a tighter focus on the threats and risks that economic interdependence entails. A postwar narrative of Europe taking back control of key supplies and pursuing more strategic trade and investment has become ubiquitous.

Crystallizing such developments, in June 2023 the commission presented a landmark economic security strategy.7 In 2024, the EU strengthened commitments to move further in this direction, bringing slightly different terms coming into use. The influential report on European competitiveness presented by former Italian prime minister Mario Draghi in September 2024 called for “a genuine EU “foreign economic policy” that is in tune with security interests.8 The European Commission’s political guidelines for 2024-2029 promise a “new economic foreign policy” premised on the conviction that, “In today’s world geopolitics and geoeconomics go together. Europe’s foreign and economic policy must do the same.”9 The remit of incoming High Representative, Kaja Kallas, includes the instruction to “shape a new foreign economic policy, focusing on economic security and statecraft.”

Significantly, the heightened focus on economic security appears to entail a new relationship between economic and political strategy. The EU’s stated priorities have become more explicitly political-strategic in nature. Some argue that in the wake of the war, the EU has moved fast to adopt a “geo-dirigisme” that deploys economic tools for strategic aims.10 European leaders insist that the new approach to economic security fuses economic and political interests as it seeks to curtail and manage the strategic vulnerabilities of interdependence. The combined effect of more than a decade of financial crisis, the coronavirus pandemic, tensions with China, and the invasion of Ukraine has propelled the EU toward a more evidently strategic variant of economic statecraft.11

The EU’s emerging approach nominally embodies a rebalanced position between economic efficiency and geopolitical resilience to the extent that European powers now appear willing to bear a premium to achieve political insulation from other powers’ leverage.12 French President Emmanuel Macron has insisted that strategic coherence is now much tighter as EU economic policies “obey a rationale which goes beyond the purely economic logic.”13 The 2023 German national security strategy captured this ethos by saying that the government would “focus more on security when it comes to decisions on economic policy.”14 The EU’s economic security strategy points to economic decisions “merging with national security concerns.”15

In a speech in June 2024, anticipating one of the core themes of his report on European competitiveness, Mario Draghi captured the zeitgeist: “The paradigm which brought us prosperity in the past was designed for a world of geopolitical stability, which meant that national security considerations played little role in economic decisions,” whereas deteriorating geopolitical conditions now required “a fundamentally different approach” to Europe’s industrial policies and “a genuine ‘foreign economic policy’ – or as it’s called today, statecraft.”16

European governments and EU policymakers argue that a hardened policy of economic security dovetails with tougher geopolitical strategies.17 Indeed, the general assumption is that these are two sides of a single strategic-adjustment coin and two strands of the EU adapting to the more threatening and inhospitable world that is taking shape in the shadow of Russia’s war on Ukraine. Outgoing EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy Josep Borrell has asserted that “de-risking and strategic autonomy go hand in hand.”18

The EU has established a mechanism to screen inward investment, and more European states are also undertaking tougher national security reviews of such investment. The union’s economic security strategy promises a new EU mechanism to assess security risks linked to outward investment in some technology sectors too, to prevent critical technologies from going to strategic rivals. The same strategy also recommends a more coordinated approach to tightening export controls on dual-use goods. Following the strategy’s adoption, the commission recommended that EU member states assess the risks associated with four areas of critical technology.19 In January 2024, the commission outlined five new initiatives to build on the economic security strategy and take it forward.20 In a separate element of economic statecraft, European powers have made trade offers more dependent on reciprocity, while due diligence rules have become another tool for strategically managed trade.

Competing Logics at Play

Although these changes in the EU’s economic posture are significant, the fusion of political-strategic and economic statecraft remains embryonic. A tougher approach to market access and sensitive exports and investments may be justified and overdue, but the EU’s assertion that economic policies are now tailored to wider strategic imperatives is a bolder claim that is so far only partly borne out by the evidence. In fact, several logics are simultaneously at play in shaping the EU’s incipient economic statecraft, some of which are at odds with each other and none of which is clearly predominant.

Even if signs of a more political-strategic dynamic have emerged, parts of the EU’s economic security agenda reflect narrower commercial aims. Alongside elements of a new EU economic statecraft, a revived European mercantilism is evident in some key policy developments. What is needed for short-term commercial interest may be an important element of economic security, but this is not the same as strategically oriented economic statecraft—despite EU leaders’ tendency to conflate the two.