The Russian army is not currently struggling to recruit new contract soldiers, though the number of people willing to go to war for money is dwindling.

Dmitry Kuznets

{

"authors": [

"Artyom Shraibman"

],

"type": "commentary",

"blog": "Carnegie Politika",

"centerAffiliationAll": "dc",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center"

],

"collections": [],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center",

"programAffiliation": "russia",

"programs": [

"Russia and Eurasia"

],

"projects": [],

"regions": [

"Eastern Europe",

"Belarus"

],

"topics": [

"Economy"

]

}

Source: Getty

Even before Makei’s sudden death, it was hard to see how Minsk could ever return to its multi-vector foreign policy as long as Lukashenko remains in power, not to mention while the fighting rages in Ukraine.

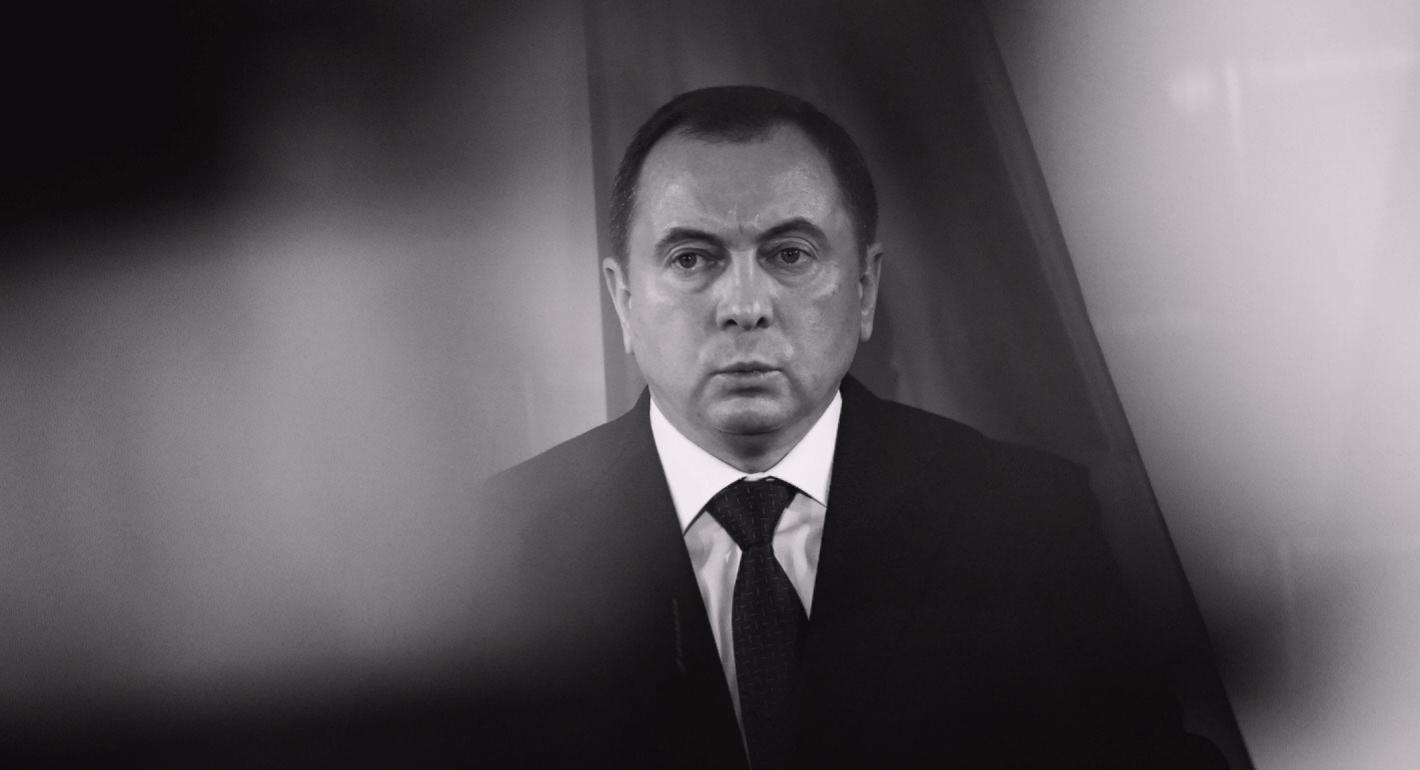

Belarusian Foreign Minister Vladimir Makei, whose death from an apparent heart attack was reported on the weekend, was the country’s most prominent official after dictator Alexander Lukashenko. One of few figures with staying power at the top of the Belarusian regime, Makei had worked as a presidential aide from 2000 before becoming head of the presidential administration in 2008 and going on to head up the Foreign Ministry in 2012.

In his ten years in office, he had gained a reputation as the main pro-Western voice in the Belarusian regime. It is hardly surprising, then, that his sudden death at sixty-four has given rise to a multitude of conspiracy theories: especially since he was working right up until his death, and appeared to be perfectly healthy.

For now, however, those theories remain nothing more than speculation. What is known is that Makei was the face and the driving force behind the longest-lasting rapprochement between Minsk and the West following the start of the Russia-Ukraine conflict in 2014.

Makei used what opportunities were available to him to set Minsk on a foreign policy trajectory of neutrality, which inevitably entailed some distancing from Russia. In his own words, he wanted to see Belarus become “an Eastern European Switzerland.”

Makei was more likely than other senior officials to speak in Belarusian, rather than Russian. He forced out the high-handed Russian ambassador Mikhail Babich in 2019, and during his time at the presidential administration, he purged the ranks of the state apparatus of the most offensive proponents of the Moscow-centric “Russian world” concept long before the process of “Belarusianization” entered the ideological mainstream.

Because of his background, many in both Belarus and the West looked to Makei with hope during the 2020 mass protests against the Belarusian regime. He appeared to be the primary candidate for a senior official who might resign in solidarity with the protesters, or even go over to join their ranks, paving the way for the schism within the elites that would be essential for a successful revolution.

But these hopes were disappointed. It seems that the strength of the minister’s convictions had been overestimated, and that for Makei, his more progressive style compared with other officials was just that: a style, a method of getting the job done, rather than an ideology.

Those who worked with Makei or regularly came into contact with him describe him not as a liberal or a covert dissident, but as an authoritarian leader skilled at navigating the various intrigues of the nomenklatura, and a shrewd negotiator prepared to tell his foreign counterparts what they wanted to hear.

At the critical moment, Makei’s loyalty to the Lukashenko regime proved stronger precisely because for him, rapprochement with the West and distancing from Russia were not the end goal, but merely a way of strengthening the system. As the Kremlin’s appetite for controlling the post-Soviet space grew, a balanced and multi-vector foreign policy gave the Belarusian regime a better chance of survival.

It will be hard for Lukashenko to find a replacement for Makei who could match him in terms of experience and standing among the nomenklatura. The Foreign Ministry’s role within the system, which has already been battered by several waves of cuts and purges in recent years, will likely decline even further as a result of his death.

Right now, the Belarusian Foreign Ministry could be abolished entirely and it still wouldn’t make much difference to Minsk’s role in the region or its ability to foster relationships with its remaining partners. Connections with its main partner, Moscow, have in any case always been the preserve of Lukashenko himself, along with the government, and, increasingly in recent times, the military.

Makei may have been an influential figure back when the regime had staked everything on a delicate balancing act in its foreign policy, but the isolation of Belarus following the 2020 crackdown and its subsequent complicity in Russia’s war against Ukraine (Belarus allowed Russian troops to use its territory as a staging ground ahead of the invasion of Ukraine) had already left Belarusian diplomacy with so little room for maneuver that his death will change little.

Following the failed Belarusian revolution in 2020, Makei was no longer warmly received in many Western capitals. It was obvious how far his political standing had declined within the system thanks to its domination by the siloviki, or security services, and Lukashenko’s descent into Russia’s embrace.

Nor had anyone forgotten that in the summer of 2020, Makei was insisting to Western diplomats that all the opposition candidates running in his country’s presidential election had been sent by the Kremlin to derail relations between Minsk and the West. A few months later, in the fall, he was just as insistent that the West was behind attempts to foment revolution in Belarus in order to drive a wedge between Minsk and Moscow.

Still, even in recent months, Makei had tried to send certain signals to his Western counterparts. Back in the spring, he wrote a letter to several European ministers, asking them to lift sanctions and promising that the Belarusian army would not fight in the war between Russia and Ukraine. In September, he met with officials from the U.S. State Department and European foreign ministries on the sidelines of the UN General Assembly, apparently trying to sell them Lukashenko’s plans for an amnesty of political prisoners, among others.

His efforts were to no avail. Instead of a response to his letter back in the spring, one of the European diplomats leaked it to the media. The meetings in New York seemingly came to nothing either: not long afterward, Lukashenko excluded political prisoners from the draft law on the amnesty, despite his earlier assurances.

Even before Makei’s sudden death, it was hard to see how Minsk could ever return to its multi-vector foreign policy as long as Lukashenko remains in power, not to mention while the fighting rages in Ukraine.

Makei’s role could be compared to a two-way signal amplifier between Lukashenko and the West. Without him, the signal would have been worse, and on occasion would have been lost completely. But to attract the West’s attention now, Minsk would have to make such radical changes in both domestic and foreign policy that there would be no confusing the message. By far the greater difficulties, therefore, will lie not in getting the West to hear that message, but in getting Lukashenko to embark on those changes at all.

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

The Russian army is not currently struggling to recruit new contract soldiers, though the number of people willing to go to war for money is dwindling.

Dmitry Kuznets

The risk posed by Lukashenko today looks very different to how it did in 2022. The threat of the Belarusian army entering the war appears increasingly illusory, while Ukraine’s ability to attack any point in Belarus with drones gives Kyiv confidence.

Artyom Shraibman

What should happen when sanctions designed to weaken the Belarusian regime end up enriching and strengthening the Kremlin?

Denis Kishinevsky

Lukashenko is using the same approach in his dealings with Trump that has long proven successful with Putin.

Artyom Shraibman

The future of the Belarus track will depend less on Minsk’s intentions than on whether the EU can move beyond symbolic unity and adopt a strategic approach toward a neighbor central to Europe’s security architecture. Without a more active EU role, these processes will unfold under conditions set entirely by Minsk and Moscow.

Balázs Jarábik