Which will we run out of first: oil or air? Will we deplete our oil and gas fields, amid infinitely growing fuel prices, or we will exhaust the planet’s atmosphere by burning that fuel, which will make carbon extraction restricted, increasingly taxed, or even banned? What we think will happen in the future defines our views, ideas, and actions in the present.

I believe the question of which will run out first is a crucial one that divides the global community more than anything else. Every political position or cultural worldview follows on from different responses to this question. As the French philosopher Bruno Latour wrote in his final essay, now every war and every election are battles in the Great Climate War. The Russia-Ukraine war is its decisive battle.

Much has been said about the ideology of this war: that it is a revanchist, imperialist war, being fought for the past, with the aim of restoring the Soviet Union. Yet imperialist wars are traditionally described as wars for resources. Historical empires fought wars for colonies that had, or were imagined to have, valuable commodities such as gold, ivory, rubber, or oil. Yet there is nothing in Ukraine that the Russian Federation does not possess in its own enormous territory. Moscow has for many decades exploited the resources of its Siberian colony, supplying about half of the Russian budget. On the contrary, by invading Ukraine, Russia has lost its traditional European market for that same Siberian oil and gas, and also now faces obstacles getting its exports onto other markets.

From the outside, this war looks like an uneven exchange of something material for something ideological, or even mythical. By fighting against the future for the sake of the past, Russia isn’t just battling for its former victories. It is fighting for its resource market, which had flourished in the past but came under threat in recent years.

The age of climate change and digital work—the Anthropocene—has put Russia’s oil and gas trading in mortal danger. Its traditional customers—European countries, Japan, and even China—have committed to cut this trade in radical though different ways. The Russian invasion of Ukraine is an imperialist war, but the purpose is not to conquer new colonies in search of new commodities. It is to force the old colonial trade on its customers. Outdated for the world but vital for the aggressor, this imperialism imposes an ancient, enviably profitable trade on its partners by force, despite modern changes, risks, and commitments. This type of self-preserving imperialism is far from new to the world.

Russian Imperialism

In contrast to the Russian Federation, the Russian Empire was deeply integrated into European politics. Russian soldiers took Berlin in 1760, Paris in 1814, and Budapest in 1848, but they did not do it alone: every time, the Russian Empire was part of an international coalition. Founded as a military capital, St. Petersburg was also a center of diplomacy. Always a hyperactive player, the Russian Empire extended its Great Game to Central Asia, North America, and the Middle East. While some of these imperial wars were launched for the sake of new colonies, other wars punished those who blocked established trade routes or refused to buy obsolete materials. Seeking new resources and creating new transportation routes for the ongoing trade with its loyal customers, the empire imposed old modes of trade on disloyal ones.

The Soviet collapse led to the liberation of fifteen countries, including Ukraine and Russia. It was a great example of the peaceful transformation of an empire, and part of the success story of global decolonization. However, the Russian loss of territory was smaller than that experienced by the British empire when it lost its colonies. The large-scale violence that tends to accompany the end of empires was only deferred. And most importantly, the Russian Federation kept Western Siberia, with its enormous oil and gas fields. This internal colony and treasure trove saved the Soviet Union, or at least deferred its collapse for a couple of decades. In the new century, it saved the Russian Federation, or deferred its collapse.

Throughout the twentieth century, Russia’s borders shifted almost as often as the most unsettled parts of the Global South. Reconquering the Caucasus and Crimea that had belonged to the Soviet Union, the new Russia identified with Soviet might and glory. Each step toward reconquering Chechnya and Ukraine was a major step toward subjugating the lands and people of Russia to a new dictatorial regime that had nothing to do with Soviet socialism. Unlike classical imperialism, which sought new resources and adventures, Putinism is revanchism: a less common but particularly toxic kind of imperialism.

Imperial Trade

Having visited St. Petersburg in 1839, in the wake of the Russian army’s brutal suppression of yet another Polish uprising, the French author the Marquis de Custine wrote that the Russian Empire was an “enormous prison, and only its emperor has the keys.” In 1914, Lenin called the Russian Empire “a prison of nations.” In 2022, the words “empire” and “imperialism” became the most common terms for explaining Russia’s aggression against Ukraine. In January 2023, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky criticized the appeasement efforts of some European politicians as “political fertilizer for the audacity of Russian imperialism.” Comparing the Ukrainian war for independence to the American War of Independence from the British Empire, Ukrainian officials predict the disintegration of what remains of the Russian Empire. Zelensky forecasts that the victory of Ukraine will be “the greatest [event] in the history of Europe after the fall of the Soviet empire.” Members of the Russian opposition use the same cluster of historical concepts. “Putin’s effort to restore Russia’s lost empire is destined to fail,” write Garry Kasparov and Mikhail Khodorkovsky in their pathbreaking essay.

Among multiple failures of the Russian invasion of Ukraine was the failure to explain its purpose. New explanatory tools were needed, but the ready-made formula of restoring the empire—the prison of nations—needs two important caveats. First, modern Russia is still an empire: an enormous and very fragile one. This makes the imagined task of restoring the “lost empire” entirely unattainable. From Kaliningrad to Grozny to Chukotka, contemporary Russia is a composite state that consists of many distinct members with very different resources, interests, memories, and purposes. Combining them with the centralizing, parasitic Moscow doubles the challenge. Rather than restoring former imperial glory through unavailable components such as Finland, Poland, Alaska, and Ukraine, Putin’s efforts are directed at preserving the current empire. The name of the country’s ruling party, United Russia, articulates this aim.

Second, the historical empire was never an end in and of itself for its rulers. It was the means. The purpose of colonial adventures was not the territory, but the commodities specific to the desired land, and a profitable trade in those commodities. When sailing the high seas on behalf of the Spanish emperor, Christopher Columbus was looking for gold. Crossing the Siberian rivers on behalf of Ivan the Terrible, Yermak was looking for fur. In buying Louisiana from France, Thomas Jefferson was counting on cotton. When invading the Soviet Union, Hitler targeted Ukrainian grain and Azeri oil. Many other aims and interests—living space, security guarantees, and transportation routes—added to the panoplies of imperial conquests.

Sometimes, colonization revealed the absence of the desired commodity. Columbus returned home with no gold, and Jefferson failed to cultivate cotton in Louisiana. But in other cases, new colonies meant amazing new resources—silver, spices, sugar, rubber—and enormous profits for the metropolitan centers. If partners started to lose interest in the trade, empires used their accumulated force to impose its ceaseless continuation. When cracking down on the American colonists after the Boston Tea Party, the British Empire sought to coerce them into buying tea from India, another British colony. By bombarding the Chinese, the British Empire wished to keep selling them opium, another treasure of India. It was not only military glory, historical memory, and other intangible ideas that directed imperial endeavors. Like imperial ships and Cossack wagons, every colonial project carried a natural resource in its underbelly.

Two Crimean Wars

The closest historical analogy to the Crimean War of 2014–? is the Crimean War of 1853–1856, for several reasons. First is the central role of the Crimea, though in both cases, part of the hostilities took place far from that fateful peninsula. Second, both wars were lost by Russia. Third, both wars were central manifestations or, arguably, culminations of worldwide crises. In the nineteenth-century war, this global crisis was symbolized by the fact that the war fell right between the two Opium Wars that the British Empire and its European allies waged against China.

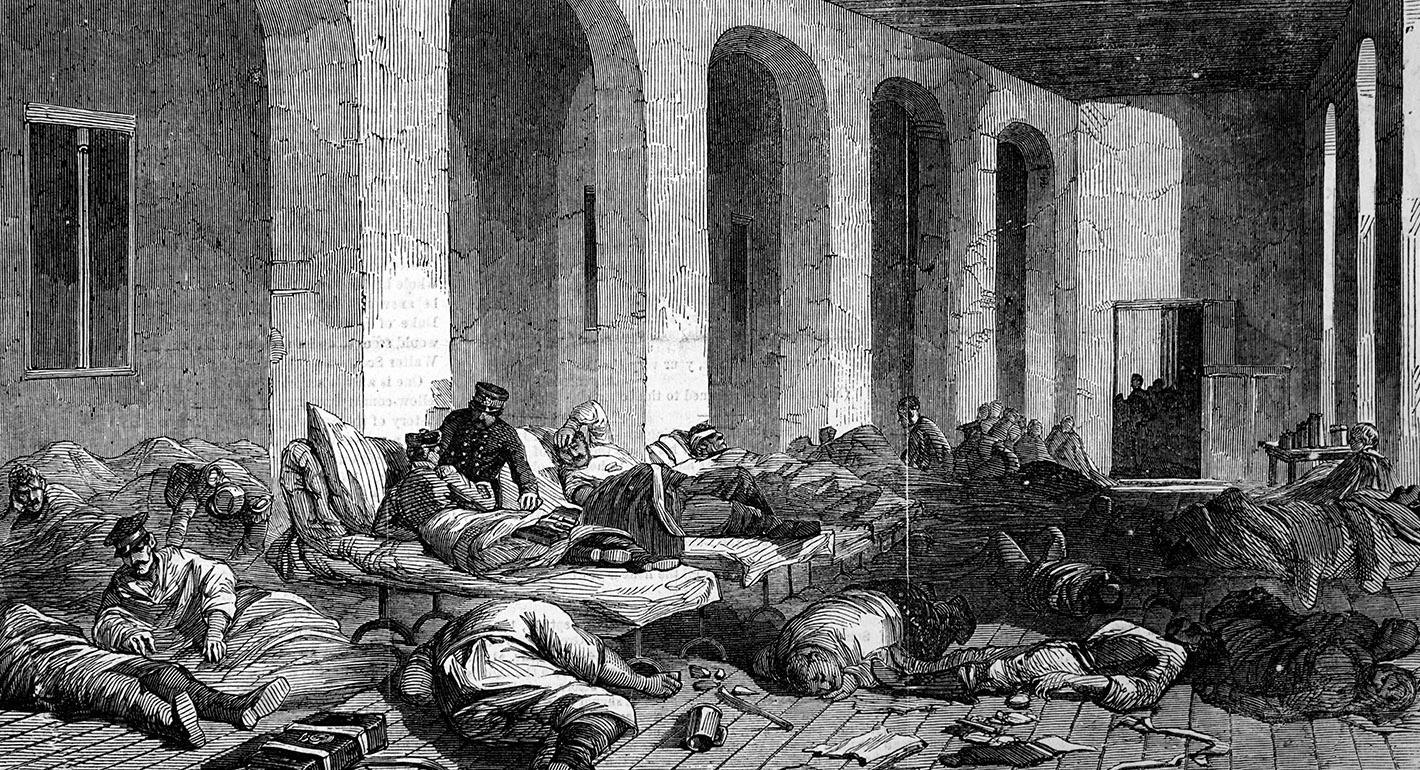

Russia has never been so isolated as during the two Crimean wars. In both, the Russian army’s logistics were poor, its weapons obsolete, its morale low, and its political masters so much older than its soldiers that they barely understood each other. In both, the anti-Russian coalition was stronger. In both, Russia’s disinformation split Western pundits. In his wartime dispatches to the New York Daily Tribune, Karl Marx wrote that “a certain class of writers” attributed to the Emperor of Russia, Nicholas I, “extraordinary powers of mind, and especially of that far-reaching, comprehensive judgement which marks the really great statesman. It is difficult to see how such illusions could be derived.” As Marx wrote, “a lot of reports, communications, etc., are nothing but ridiculous attempts on the part of Russian agents to strike a wholesome terror into the Western world.” In launching both wars, the Russian rulers talked about glory, history, and security, and some Western pundits took these words at face value. Others ridiculed them, seeing in Russia’s actions only rude and militant attempts to impose their customary, traditionally profitable methods of doing things onto the disloyal world that was looking for new ways of living.

Both Crimean wars challenged the internal structure of the Russian imperial state. In both, ethnic issues were important but not decisive. Close to the end of the First Crimean War, the British government discussed a plan for a “war of nations,” which would have involved supporting nationalist movements in the Caucasus and elsewhere so that the Russian Empire could be weakened and dismembered. The plan never came to fruition as the government in London fell, and Nicholas I died (or took his own life) at just the right time to not have to acknowledge his defeat. The new British government signed a toothless peace with the heir to the throne, Alexander II. Yet the First Crimean War led to a swift transition of power from the fathers to the sons. Alexander II chose to launch the Great Reforms of the 1860s: still the most successful attempt at modernizing Russia. We will see whether anything similar happens after Russia’s defeat in the Second Crimean War.

Imposing Trade by Force

In 1839, the Chinese emperor ordered the destruction of Indian—or more precisely, British—opium in Chinese ports and warehouses, and more than 1,000 tons were found and burned. Outraged by this interference in free trade, the British Empire declared war. Using their first military steamships, British troops forced China to pay compensation. The British obtained Hong Kong and five more ports for duty-free trade. The price of opium fell sharply, and people lower down the social scale began using it. The opium trade intensified, but not enough for the Empire. In 1856, the Second Opium War began. French and English troops joined forces to occupy Chinese ports and warehouses, liberating them for the opium trade. Undermined by opium, the Chinese lost one battle after another. After seizing Peking, the Western powers signed a peace treaty with China through the mediation of the Russian ambassador, Count Nikolai Ignatieff. China made opium use legal and ceded new ports for free trade in opium and other Western goods (and bads). In gratitude, the Russian Empire got the Amur River delta and vast territory on the Pacific: this is how Vladivostok was founded.

Before the Second Crimean War, all Russian regions were beneficiaries of the transfers of wealth that came from a small number of internal colonies: the oil-pumping and gas-trading regions at the center of the Eurasian continent. The biggest donors were two “autonomous districts” named after their indigenous populations that had become largely extinct: the Khanty-Mansi and Yamalo-Nenets regions, a vast land of empty marshes and migrating reindeer in Western Siberia. Another donor was Moscow, the official residence of many extractive corporations that drill and mine in Siberia but pay taxes in the capital. Nevertheless, Khanty-Mansi delivered so much and consumed so little that the region contributed twice as much to the Russian budget as Moscow.

Year after year, fossil fuels that polluted the global atmosphere made up more than two-thirds of Russia’s exports, and from a quarter to a third of its GDP. The lion’s share of this money came from Europe, which in 2021 bought three-quarters of Russia’s gas exports and two-thirds of its oil exports. That money was crucial for the stability of Russia’s currency, for arming its military, for maintaining the luxurious lifestyle of its elite, and for importing consumer goods for the general population. Russian exports provided about 40 percent of the EU’s gas, about half of its coal, and a quarter of its oil.

The relationship was symbiotic, though Russia depended on it more than Europe. The EU’s energy transition means replacing products extracted from nature with goods created by labor, which would inevitably have resulted in a major reduction in Russian profits. Despite all the talk of modernization and diversification, there was no plan for substituting Russia’s fossil fuel exports with any other source of revenue. And if there were hopes of cheating the planet through the EU Emissions Trading Scheme (2009), there was no way around the EU Transborder Carbon Tax (2021). The continuation of this toxic trade was only possible if it were imposed by force.

Euro-Atlantic leaders imagined decarbonization as a process of cooperation and shared sacrifice. Many of them also had doubts and fears regarding decarbonization, but only the beneficiaries of the oil and gas trade knew precisely how much they stood to lose if the trade ceased. The truth was that sellers of hydrocarbons would suffer more than buyers. For various reasons, state actors and climate activists underestimated this structural asymmetry. With some naivety, they thought that climate awareness would be equal at all nodes of the fossil trade. But Russia’s policies turned the common cause into a zero-sum game.

In April 2021, the EU declared its commitment to halving emissions by 2030 and achieving net zero by 2050. That would mean proportional reductions of oil and coal purchases, while gas, a cleaner fuel, would keep flowing for another decade. “You see what is happening in Europe. There is hysteria and confusion on the markets,” Putin said in October 2021. By that point, Russia’s war preparations were in full swing. The Second Crimean War was launched to impose the continuation of the oil and gas trade on a detoxing Europe. Russia underestimated the West’s reaction, just as it underestimated the Ukrainian resistance. European plans for decarbonization have been partially deferred because of the war, but Russia will never regain its Western markets for fossil fuels. Russia’s desperate fight is lost: the future is coming.