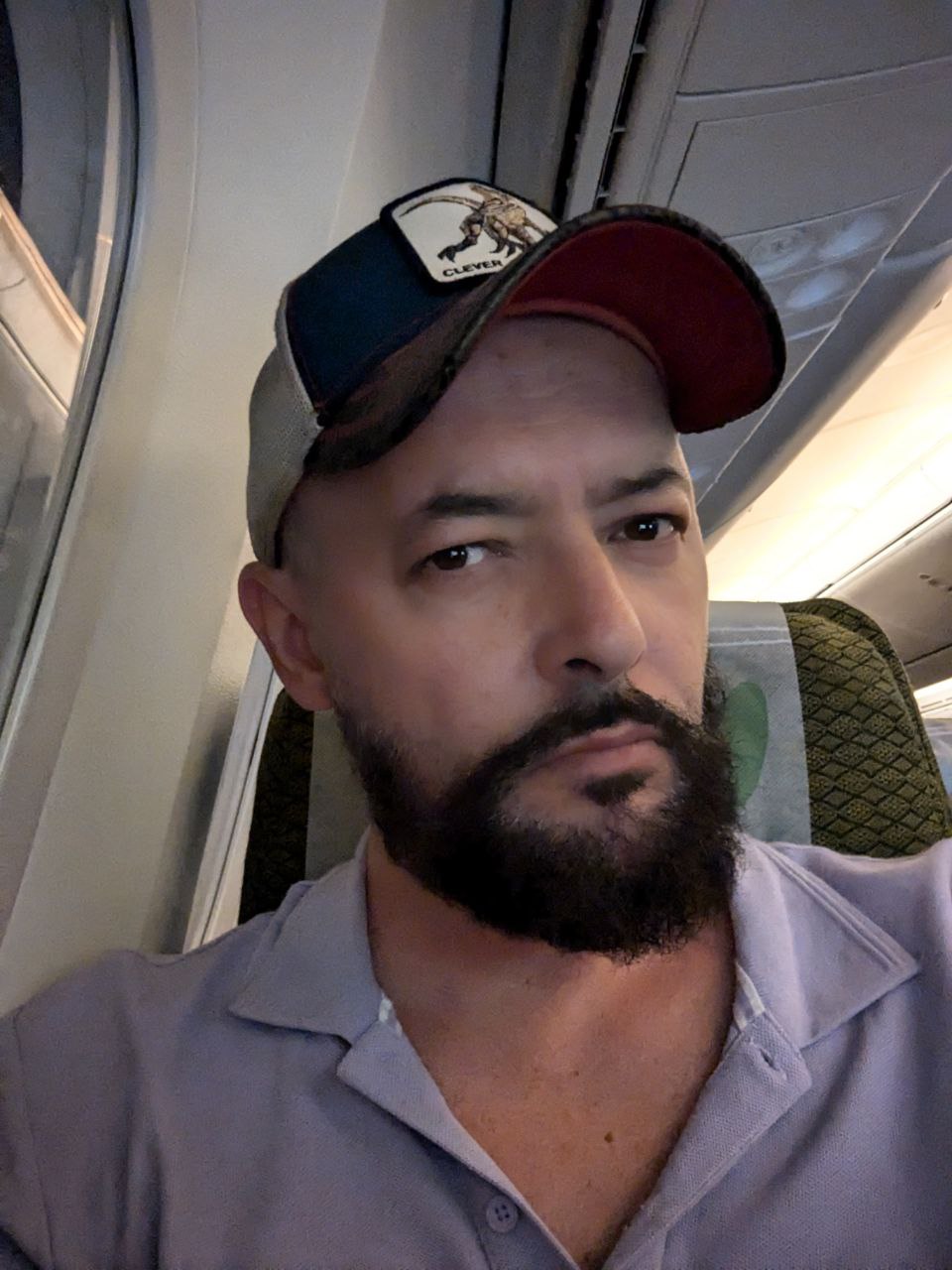

President Maia Sandu will face an unexpected opponent in Moldova’s October elections: Alexandr Stoianoglo. A political newbie and former prosecutor general, Stoianoglo is hoping to become the sole opposition candidate to take on the pro-Europe Sandu. While his lack of public political profile is a potential problem, it also makes Stoianoglo a far more dangerous opponent for Sandu than most of Moldova’s established pro-Russian leaders.

Stoianoglo’s announcement that he would stand made the headlines in Moldova, and will likely remain at the top of the news agenda for some time. Firstly, Sandu has not previously faced an opponent able to challenge her political dominance. Secondly, Stoianoglo is seeking to be a unified opposition candidate. “I’m not a politician,” he said recently. “But, at the same time, I’m able to find a common language with many Moldovan politicians.” Thirdly, Stoianoglo’s presidential bid is supported by the pro-Russian Party of Socialists. Its leader, ex-president Igor Dodon (the country’s most popular opposition politician), caused some surprise when he announced he would not run in order to clear the field for Stoianoglo.

Furthermore, Dodon has appealed to other opposition groups to follow his lead and ensure Stoianoglo is the only challenger to Sandu. No one has yet responded to Dodon’s call, but the gesture itself—unusual for Moldovan politics—is significant. Stoianoglo has said that discussions about whether other opposition groups will put forward candidates are still ongoing. Their outcome is unpredictable, but something interesting is afoot.

Support from Dodon and the Party of Socialists cuts two ways. On the one hand, the former president is bestowing some of his popularity on Stoianoglo. On the other hand, Dodon and his party are not just seen as pro-Russian: many think they are managed directly from the Kremlin.

More than one commentator has claimed that Stoianoglo’s candidacy is part of a Kremlin plot, and Sandu has also aired this theory. “The oligarchs and the Kremlin have come to an agreement and found their preferred candidate,” Sandu said when asked about Stoianoglo. “It’s clear that the Kremlin wants to see thieves return to power in Moldova. Because the Kremlin knows that thieves will sell out our country and then it can use us for its own aims.”

Sandu’s position was predictable. More unusual was her decision to speak publicly about a candidate whose popularity with the electorate is unknown (there have been no opinion polls on Stoianoglo yet). The unspoken rule in politics is that the favorite in an election should ignore their opponents to avoid giving them airtime—after all, bad PR is also PR.

However, the Moldovan authorities have gone even further. Three days after Stoianoglo announced his candidacy, it emerged that a Moldovan court would proceed with hearings in a criminal case against him for alleged abuse of power when he was prosecutor general. Prior to this, there had been no developments in the case for eighteen months.

That news will likely play to Stoianoglo’s advantage, allowing him to assume the role of victim. From now on, it will be difficult to see the actions of law enforcement as anything other than political. The Moldovan authorities already have a reputation for prohibitive solutions: battling Russian propaganda by shutting down TV stations without a court order, or blocking candidates from standing for election because they are seen as Kremlin agents.

Embracing such an image would not be a new departure for Stoianoglo, who has been cultivating the role of a victim ever since Sandu was first elected as president in 2020. Once in post, Sandu began to express her unhappiness with the Prosecutor General’s Office, which Stoianoglo headed, over its failure to investigate high-profile criminal cases involving Moldovan oligarchs who previously wielded significant influence. Initially, Sandu did not have the power to remove Stoianoglo. But when her Party of Action and Solidarity (PAS) won parliamentary elections in 2021, her team was finally able to get him fired.

Stoianoglo’s dismissal then became a political scandal after the government failed to produce convincing evidence of his wrongdoing. PAS deputy Lilian Carp tried to prove Stoianoglo had links to oligarchs by alleging that notorious Moldovan businessman Veaceslav Platon (currently on the run in London) had registered several Ukrainian companies in the name of Stoianoglo’s wife. Yet Carp never produced sufficient proof. In 2023, Stoianoglo won a case against Moldova in the European Court of Human Rights, which ruled that his right to a fair trial had been violated. To this day, the “Stoianoglo case” remains one of the Moldovan government’s biggest embarrassments.

Now Stoianoglo has decided to take on his critics and exploit the victim status that has been gifted to him by the authorities. Of course, that’s unlikely to be enough for the former prosecutor general to become a serious challenger to Sandu. It’s no coincidence that Stoianoglo immediately voiced his support for EU integration, in an attempt to muscle in on an issue that is most associated with Sandu.

Another looming problem is that while Stoianoglo’s politics are not yet fully defined, the support of the pro-Russia Party of Socialists means he has limited room for maneuver. He can’t afford to ignore left-wing voters, many of whom are pro-Russian, and he will soon be obliged to express an opinion on major issues like Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. He will also need to lay out his vision for Moldova’s European integration, and explain why he would be better able to deliver than Sandu, whose leadership has seen Moldova granted EU candidate status and the start of formal accession talks.

All this means that a Stoianoglo election victory is very far from guaranteed. But he has managed to generate shock waves through Moldovan politics and create intrigue around the outcome of a vote that appeared until recently to be a done deal.