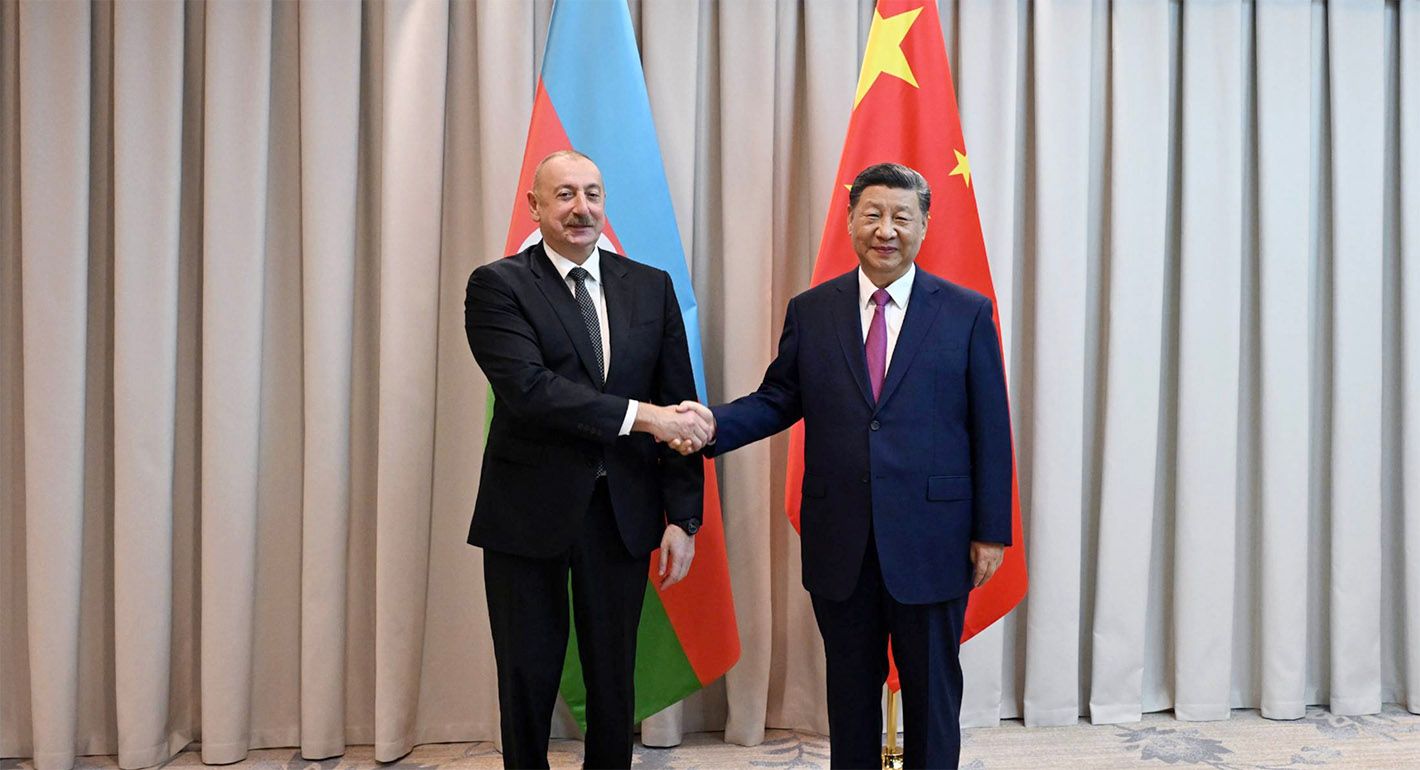

Azerbaijan has become China’s second strategic partner in the South Caucasus—a year after Georgia—with the two countries signing a joint declaration on July 3 spelling out wide-ranging areas of cooperation.

China had long seemed a promising partner for Azerbaijan, but political and economic cooperation only got going in 2015, when the Azerbaijani manat was devalued amid falling oil prices, prompting Baku to seek fresh investment. Key agreements were signed, including ones to boost trade and to jointly promote China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Trade turnover almost quadrupled from $561 million in 2015 to $2.1 billion by 2019.

Since Azerbaijan’s success in its 2020 war with Armenia, China’s interest in the South Caucasus has grown. It hopes Baku and Yerevan will make peace and open up a second trading route to Europe via Azerbaijan, southern Armenia, the Azerbaijani exclave of Nakhchivan, and Türkiye. That would complement an existing route via Azerbaijan and Georgia which is part of the Middle Corridor, a land route from China to Europe that bypasses Russia. This has gained momentum as sanctions over the Ukraine war have made Russia’s vast rail network, previously the main east-west land route, more problematic. China, Central Asia, and Azerbaijan are now working more closely to enhance the Middle Corridor’s role in the BRI, a drive to develop more efficient trade routes. For Azerbaijan, this is a boost for its broader regional ambitions, especially in Central Asia.

Firstly, therefore, the strategic partnership document focuses on the safety and uninterrupted operation of international transport corridors. In October 2023, the national railways of Kazakhstan, Georgia, and Azerbaijan agreed to establish a joint venture that will synchronize their customs and electronic systems so that goods from China can pass through a unified checkpoint, aiming to cut freight delivery times between China and Europe. In the declaration, China pledges to help develop and use the Middle Corridor, a central interest for Baku, which hopes Beijing will prioritize it in its trade connections with Europe. Without China’s support, the Middle Corridor is less likely to become a key transport route. Azerbaijan is also very keen for China to help develop the Middle Corridor’s physical infrastructure, and sizeable immediate investment is needed to make the route competitive. For Baku, such investment would show Beijing’s long-term commitment to the Middle Corridor.

Secondly, the document pledges both sides’ support for a multilateral trading system under the auspices of the World Trade Organization (WTO), along with China’s backing for Baku’s full accession. This could encourage Azerbaijan to expedite the long process of joining the body to which it applied for membership in 1997, a process delayed by Baku’s desire to protect its agriculture and non-oil sectors. China’s influence could prove to be a deciding factor. Membership would reduce tariffs on Azerbaijani exports to WTO countries—i.e., to China and much of the world, including most neighbors, though it may not significantly alter Baku’s massive trade imbalance with China. Bilateral trade hit $3.1 billion in 2023, up 40 percent from the year before, as China overtook Türkiye as Azerbaijan’s second-largest source of imports. Over 95 percent of the trade in 2023 was asymmetric, favoring China, as Azerbaijan increased its imports of smartphones and vehicles. WTO accession could help put at least a small dent in this by making Azerbaijani agriculture, petrochemicals, and textiles more competitive.

Thirdly, Azerbaijan explicitly said for the first time that it wanted to join the growing BRICS group of major developing countries, which would add a new dimension to Baku’s international engagement. Unlike its neighbors, Azerbaijan does not aspire to European Union integration, nor is it part of any large multinational economic bloc. Its strategic ally Türkiye has also recently renewed its interest in joining BRICS, sparking criticism for drifting away from the EU it had aspired to join, and raising concerns about a NATO member joining a bloc that includes China and Russia. Azerbaijan, however, faces no such constraints, and Ankara and Baku look set to support each other in this direction. A few weeks after the joint statement, Baku also applied to upgrade its eight-year-old legal status with the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) from dialogue partner to observer, with full membership possibly in its sights. A senior Azerbaijani diplomat told Carnegie Politika this could enhance Azerbaijan’s political and economic cooperation, trade relations with members, investment opportunities, and regional influence.

Beyond these issues, Azerbaijan’s interest in the strategic partnership centers on economic opportunities and Chinese investment. Baku has traditionally been reluctant to embrace Chinese investment, worrying that it could bypass government control or lead to the privatization of strategic assets like ports and railways. It remains cautious but seems more open to Chinese investment in rebuilding the Karabakh region. Chinese telecommunications giant Huawei, for example, was among the first foreign multinational technology corporations to invest in the region, and now more Chinese companies are following suit. Baku’s priorities also include investments in digitization and renewable energy and manufacturing electric cars in Azerbaijan in partnership with Chinese companies.

Baku is eager to boost its role in China’s strategic cooperation with Central Asia, and positions itself as a bridge between that region and the Caucasus. It wants China to expand its “5+1” format for cooperation with Central Asia (Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan) to “6+1” to include Azerbaijan. Baku also wants to be seen as part of “wider Central Asia,” a goal supported by its ally Kazakhstan, which has mediated stronger links between Baku and Beijing.

China, meanwhile, is set on expanding its role in the South Caucasus, evidenced by its investing in major infrastructure projects in Georgia and increasing trade with Armenia too.

There are, however, significant challenges. Firstly, balancing the influx of Chinese investment against the protection of strategic sectors could be difficult, though not impossible. Investors might seek influence over strategic decisions in key industries such as logistics as a condition for their investment, but Azerbaijan is not interested in compromising. The alternative, however—taking out large loans—carries the risk of the debt traps seen in other regions with substantial Chinese investment.

Beyond these challenges, steady economic cooperation with China and other international partners requires economic reforms in Azerbaijan to diversify the economy, given that the majority of the country’s exports are oil and gas, and that oil revenues are declining. While there has been some growth in non-oil sectors in recent years, those industries are still in the early stages of development. Without economic reforms in the short and long term, relying on foreign investment for economic growth is a perilous gamble, risking more than it promises to deliver.

One of the main challenges for Azerbaijan will be to calibrate its expectations of China and to carefully watch whether Beijing’s lofty promises match its deeds. Even Russia, the champion of cooperation with China among post-Soviet states, with its sizable market, geography, complementary economy, and shared opposition to the United States, is waiting for an influx of Chinese investment that so far hasn’t materialized. None of the dozens of potential joint investment projects pitched to Beijing by the Eurasian Economic Union has attracted Chinese money. In the South Caucasus, neighboring Georgia has been expecting an inflow of Chinese investment for about a decade now, with only a fraction of those hopes transformed into actual projects. It’s a similar picture around the world, including in Latin America, Eastern Europe, and many countries in Africa. The key reason is the gap between the desire of Chinese bureaucrats and businesspeople to promote Xi’s flagship geoeconomic initiatives like Belt and Road, and the economic challenges faced by the Chinese economy during the last decade.