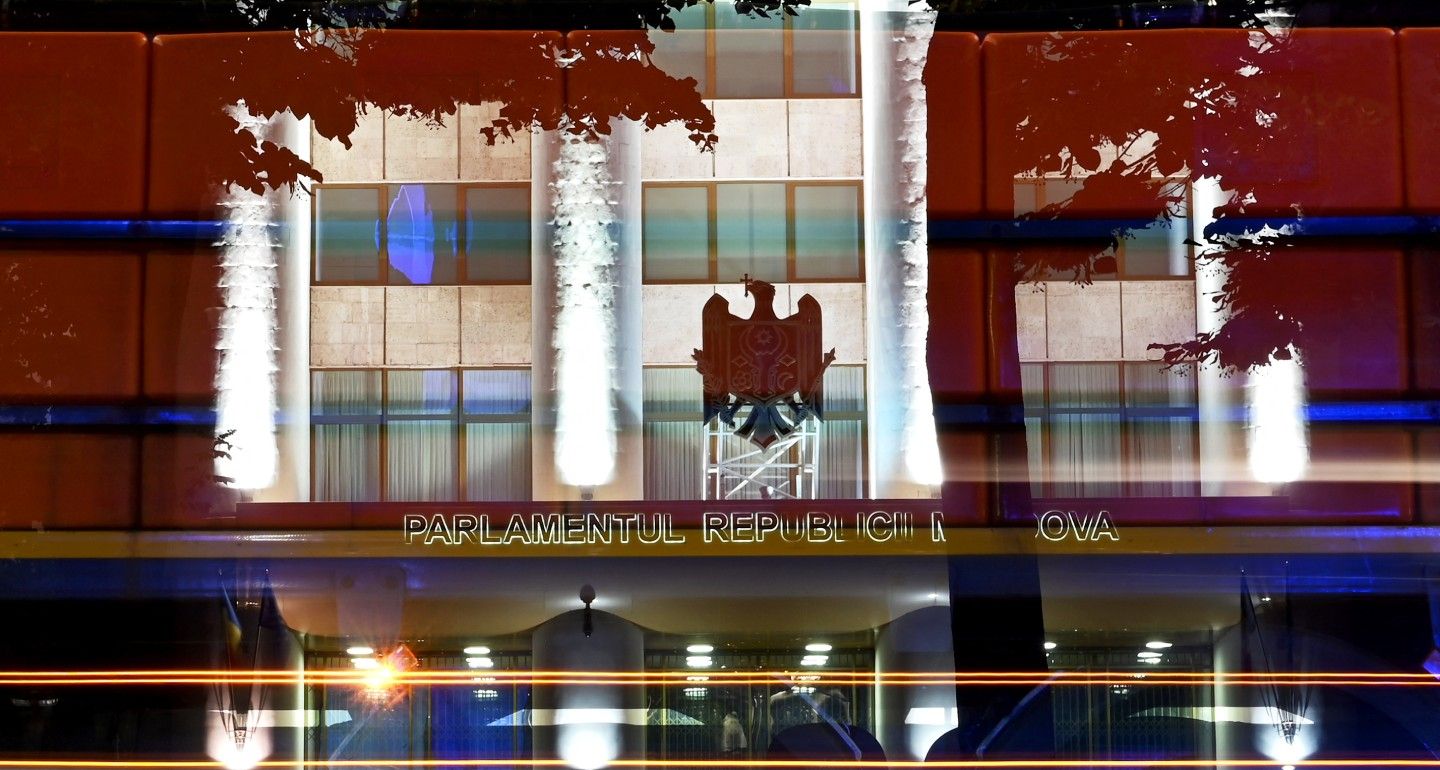

Presidential elections in Moldova scheduled for October 20—the first since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine—will show how much influence Moscow still wields in the country. Before the war, Russia’s position was fairly strong. However, integration with Europe is now even supported by those Moldovan politicians who were previously considered to be Kremlin puppets.

While there are as many as eleven candidates officially registered, the main battle looks likely to be between President Maia Sandu and former prosecutor general Alexandr Stoianoglo. Sandu is the clear favorite, with over 30 percent of voters supporting her, while polls conducted in July and August put Stoianoglo at about 10–11 percent. But things may get less predictable if the vote goes into the second round, where all those unhappy with Sandu’s leadership consolidate behind the opposition candidate.

The election will also provide an answer to the question of how much influence Russia retains in Moldova, a former Soviet republic that is sandwiched between Ukraine and Romania. The war in Ukraine triggered an immediate shift in Russia–Moldova relations, with Chisinau throwing its support behind Kyiv and freezing official ties with Moscow at all levels. Moldova has not held any bilateral meeting with Russia, nor taken part in meetings of any regional groupings involving Russia, since the invasion.

Russia previously played a significant role in domestic Moldovan affairs. In 2019, Moscow, acting in consort with Washington and Brussels, brought down the regime of the oligarch Vladimir Plahotniuc. It was the Kremlin that pressured then president Igor Dodon to make his pro-Russian Party of Socialists enter an alliance with pro-Western groups, including Sandu’s Party of Action and Solidarity (PAS).

Historically, Russia has sought to wield influence during Moldovan elections. The Party of Socialists received twenty-five seats in parliamentary elections in 2014 thanks in large part to political, financial, and media help from Moscow. Ahead of the vote, Russian President Vladimir Putin hosted Dodon in the Kremlin, and the resulting photo was widely used by Dodon’s campaign. Similarly, in 2016, Russian support helped Dodon become president.

Even Sandu didn’t take an anti-Russian position during her previous presidential campaign in 2020. Back then, both Sandu and PAS advocated for a pragmatic, mutually beneficial, and respectful relationship with Russia. The attack on Ukraine in 2022, however, led them to abandon that approach.

Today, almost every Moldovan politician wants to avoid being seen as pro-Russian. Even the Party of Socialists—traditionally considered Moldova’s most pro-Russian political force—has changed tack. While the Socialists had previously promised to bring Moldova into the Russia-led Eurasian Economic Union, their manifesto now only contains vague statements about what is best for Moldova.

Indeed, not a single one of the candidates seeking to run for president has mentioned the Eurasian Economic Union. Stoianoglo, backed by the Party of Socialists, describes himself as a supporter of further integration with Europe, and says that he will take Moldova further down the path of European Union membership if he becomes president. He also says Moldova’s relations with Russia should be “pragmatic and mutually beneficial.”

The only exception to this rule is Moldovan oligarch Ilan Shor’s political bloc Victory. Shor, who holds Moldovan, Israeli, and Russian citizenship, currently lives in Moscow (he was sentenced in absentia to fifteen years in jail by a Moldovan court for his role in the 2014 theft of $1 billion from three Moldovan banks). Shor opposes integration with the EU and supports Moldovan membership of the Eurasian Economic Union.

Shor’s activities in Moldova are carefully targeted. Since his support helped Evghenia Guțul get elected as head of Moldova’s autonomous southern region of Gagauzia in 2023, he has funded the construction of a theme park with free entry called GagauzLand, and—with Russian help—made monthly payments of about 100 euros to local state employees and pensioners. The Gagauzia authorities have said that such financial payments are being received by about 30,000 people: a monthly bill of some 3 million euros.

The idea is simple: the example of Gagauzia should convince other regions of Moldova to vote for Shor’s Victory bloc. At the moment, polls suggest Victory is supported by 8 percent of Moldovan voters, far behind PAS with 28 percent.

Russia has never been very successful when it comes to exercising soft power in Moldova. Instead, the Kremlin has always sought to back specific politicians (previously Dodon, now Shor), and relied on the bonds of a shared Orthodox faith and history (including the memory of the Soviet victory in World War II). If Moscow disapproved of the Moldovan government’s actions, it would impose economic sanctions: Russia banned imports of Moldovan wine, for example, in 2006, 2010, and 2013 amid political disputes.

The West’s approach to winning Moldovan hearts and minds is very different. For decades, the EU and the United States have funded NGOs; handed out grants to farmers, businesses, and media outlets; and financed infrastructure projects including road repairs, as well as equipment for hospitals and schools.

Still, despite the war, there remains significant support for Russia in Moldova. This is reflected both in polling data and in the number of Moldovan voters who back politicians calling for improved ties with Moscow. In a June survey by the U.S. International Republican Institute, 53 percent of Moldovans named Russia as one of their country’s most important economic partners (69 percent gave that title to Romania, and 66 percent to the EU). And 50 percent of Moldovans identified Russia as one of their country’s most important political partners—the EU came in top with 65 percent.

It’s unclear how long Russia will be able to retain this level of support. Backing Shor—a toxic figure with a reputation as a fraudster—illustrates the degradation of Moscow’s methods to further its influence. Sociologists have noted that every surge in activity by Shor and his team actually ends up boosting Sandu’s popularity. The idea of someone like Shor actually coming to power is clearly a frightening prospect.