The United States and Europe are bitterly divided over policy toward Russia and Ukraine. Despite the Russian regime’s rejection of the Trump administration’s proposal for a thirty-day ceasefire, the White House has continued its friendly attitude to Russia.

On April 2, Kremlin envoy Kirill Dmitriev was welcomed to the White House for talks with Steve Witkoff, a senior aide to President Donald Trump. According to Dmitriev, who was given a sanctions waiver to make the visit, the sides discussed the return of U.S. companies to Russia and cooperation on rare earth metals. The same day, Russia, alongside Belarus, was excluded from the list of 185 countries subjected to new U.S. tariffs. Ukraine, by contrast, was slapped with a 10 percent levy.

There are also doubts about the future of U.S. military aid to Ukraine. Reports suggest that Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth will not attend an April 11 meeting of the Ukraine Defense Contact Group in Brussels, symbolizing Washington’s disengagement from this group that coordinates the delivery of military equipment to Ukraine.

As its U.S. ally strides off in one direction and its European partners in another, what course will Japan take? The Japanese government’s sympathies lie with the Europeans. Tokyo remains steadfastly opposed to Russia’s aggression and has been generous in its support for Ukraine. Partly this is because of concerns that Russia could become a direct threat to Japan. After all, the Habomai islets that are claimed by both Russia and Japan and are home to a Russian border guard outpost are just 3.7 kilometers from Japan’s Hokkaido prefecture.

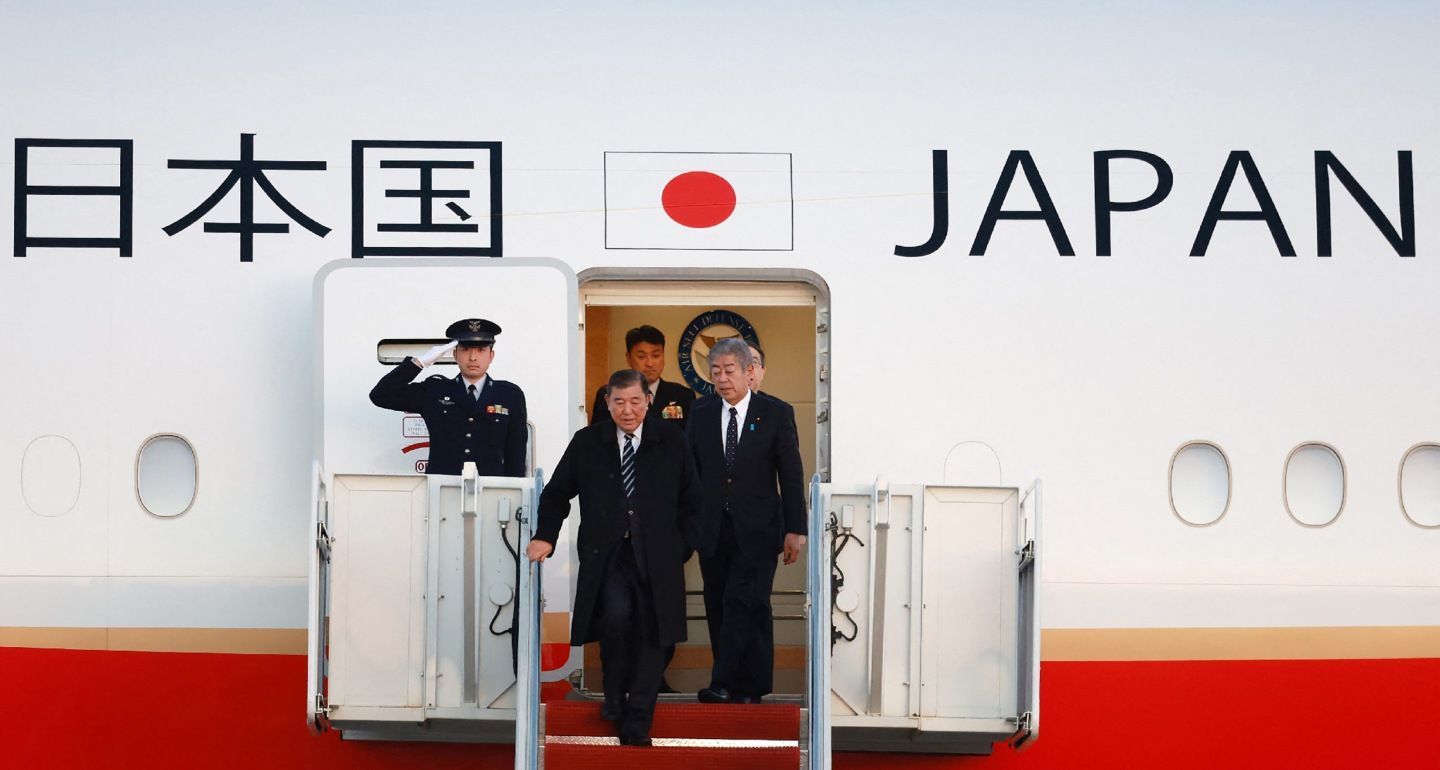

However, Japan is even more concerned by the precedent set by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. If Russia can succeed in changing the international status quo by force in Europe, China may be emboldened to do the same against Taiwan or against the Japanese-administered Senkaku Islands, which Beijing claims as the Diaoyu Islands. This is why Japan’s leaders have repeatedly warned that “Ukraine today could be East Asia tomorrow.” Russia must therefore be prevented from achieving victory in Ukraine so that, as Prime Minister Ishiba Shigeru stated in February, “no one learns the wrong lesson.”

Russia’s deepening cooperation with North Korea also encourages Tokyo to stand firm. From the Japanese perspective, North Korea is a terrorist state that has abducted Japanese civilians and regularly fires ballistic missiles into Japan’s exclusive economic zone. Moscow’s intensifying economic and military engagement with Pyongyang is therefore a security threat for Tokyo since it risks enhancing North Korea’s war-fighting capabilities.

Japan is also in the same boat as the Europeans when it comes to tariffs. Despite Prime Minister Ishiba’s desperate attempts to woo Trump at a summit in February, Japan was hit with U.S. tariffs of 24 percent: even higher than the 20 percent rate applied to the European Union.

After the shock of the tariffs, Kono Taro, an outspoken former defense and foreign minister, asked on social media, “Is this the beginning of the end? Do we need a Plan B?”

In theory, Japan could mimic Europe’s approach. That could involve pushing back against the United States by criticizing aspects of its Russia policy and threatening retaliation against U.S. tariffs. Efforts could also be made to achieve strategic autonomy by building up Japan’s own defensive capabilities. Simultaneously, greater distance from the United States could be compensated for by deepening cooperation with likeminded countries, including European partners.

This might sound appealing, but it is unrealistic in the short and even medium term.

Collectively, the European Union and United Kingdom have a population of 517 million and total GDP of approximately $23 trillion. Russia’s population is just 144 million and its total GDP a mere $2 trillion: smaller than that of Italy. In short, Europe can stand alone against Russia if it chooses to do so. This is much more difficult for Japan, whose population is 124 million (and shrinking) and whose total GDP is around $4 trillion.

Additionally, Japan is facing not just one hostile nuclear-armed dictatorship, but three. Of these, China is the most threatening. While Russia is a declining power that is raging against the dying of its regional influence, China is a genuine economic, military, and technological superpower.

All of this means that Japan’s security environment is more perilous than that of Europe. This is exacerbated by decades of Japanese underspending on defense due to a longstanding norm (only recently abandoned) that kept defense spending to no more than 1 percent of GDP. An outdated constitution, which still states that “land, sea, and air forces, as well as other war potential, will never be maintained,” also impedes Japan’s ability to defend itself.

Japan must also be realistic about what can be achieved in cooperation with European countries. Japan has partnered with the UK and Italy on the Global Combat Air Programme (GCAP) to develop a next-generation fighter jet. A UK Carrier Strike Group will also be visiting Japan in 2025.

These are welcome developments, but no combination of European countries can come close to matching U.S. military power in the Pacific. There is also the risk that European countries, faced with an aggressive Russia and an antagonistic United States, may decide that they cannot afford to also have tensions with China. That could cause European states to shy away from actions in Asia that could provoke Beijing.

For Japan, therefore, much more so than for European countries, there is no alternative to the United States.

Given its security dependence on the United States, Japan’s short-term priority will be to minimize the appearance of foreign policy differences with Washington and, above all, to avoid angering President Trump. There are already some signs of this. When the Trump administration temporarily halted military aid to Ukraine, Japan adjusted its own rhetoric. Having previously promised to “strengthen” support for Ukraine, Japan quietly downgraded this to “maintain” support.

Such caution will also characterize Japan’s response to U.S. tariffs. While several countries, as well as the European Union, have been quick to threaten retaliation, Japan will try to negotiate a deal and will use financial resources to cushion the blow to domestic industries.

However, while Japan will cling tight to the United States for the foreseeable future, policymakers in Tokyo must now consider a wider range of longer-term options. That will include derisking. Until now, this term has been used to describe efforts to reduce Japan’s economic dependence on China. Now, Japan must also derisk by reducing security dependence on the United States.

This will entail increasing defense spending beyond the current goal of 2 percent of GDP by 2027. NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte has spoken of the need for NATO members to go “north of 3 percent.” Japan would be wise to adopt the same benchmark. The vexed issue of constitutional revision will also have to be finally addressed to provide an explicit legal basis for Japan’s Self-Defense Forces.

Lastly, unable to rely on the United States as it once did and facing the triple threat of China, North Korea, and Russia, Japanese policymakers must contemplate the most taboo topic of all. Despite being the only country to have suffered atomic attacks, Japan too may need to seriously consider the development of nuclear weapons.