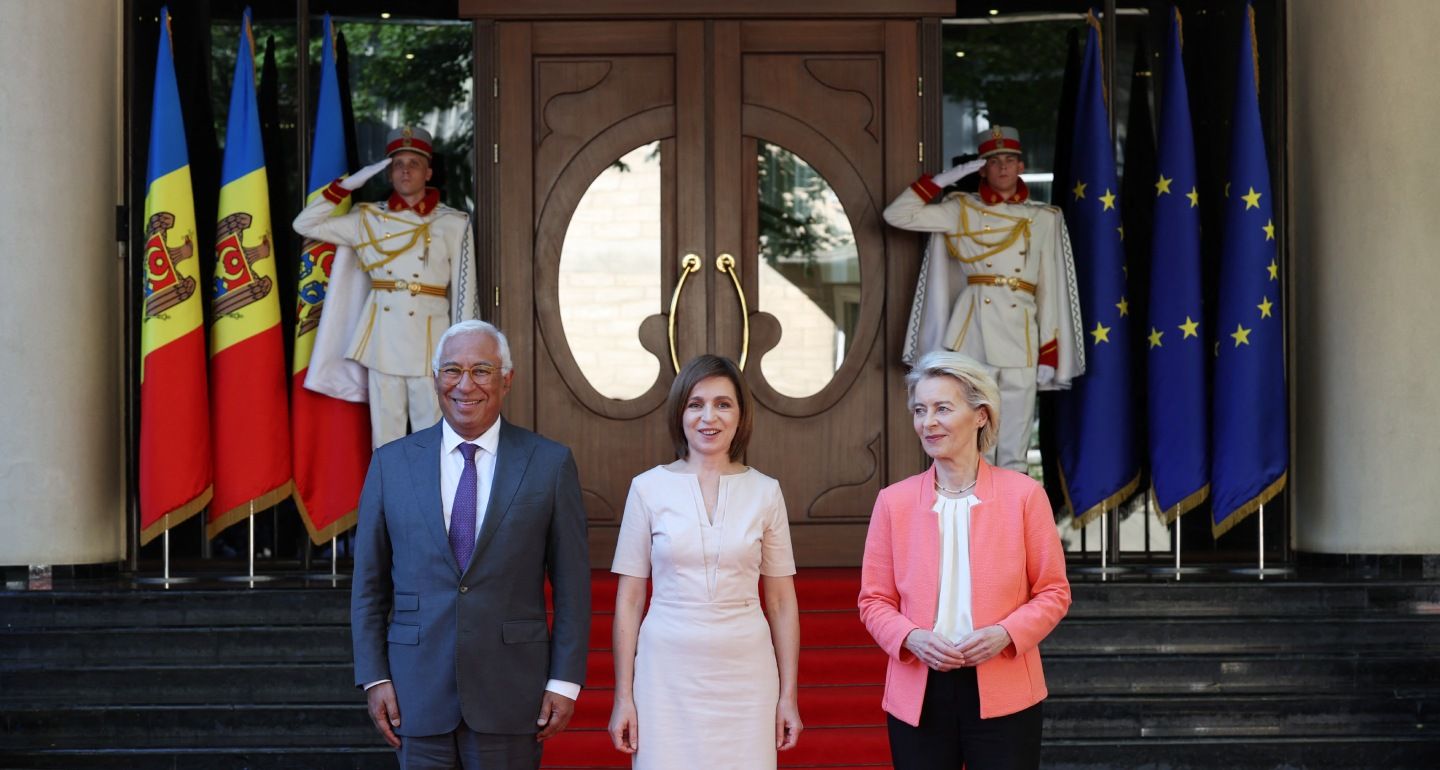

The bilateral summit between the European Union and Moldova that took place on July 4 will likely go down as a milestone in modern Moldovan history. It was the first such event in Moldova’s more than two decades-long journey toward EU membership: a journey that has often been shaped more by geopolitics than by decisions taken in Chișinău. Such EU summits are usually only held with major powers like the United States, United Kingdom, and China.

This type of summit, which marks a genuine elevation of the political relationship between the EU and Moldova, will now be a regular occurrence. While such events are undoubtedly a success for Moldova’s current pro-EU government, in other policy areas its track record is far less impressive.

The victory of Moldova’s Party of Action and Solidarity (PAS) in the 2021 parliamentary elections was not due to its pro-EU slogans, but to its promises to solve pressing domestic issues. However, among the thirteen major problems PAS promised to tackle (from fighting corruption to building a robust economy), it’s difficult to identify a significant positive change on many of them.

Not a single major corruption case over the last four years has resulted in a jail sentence. Notorious tycoons Vladimir Plahotniuc and Ilan Șor, who have been implicated in the theft of $1 billion from Moldovan banks eleven years ago, have fled the country and remain at liberty, meddling in Moldova’s domestic politics from abroad.

None of the prosecutors, judges, and politicians who abetted Plahotniuc’s capture of the state in 2015–2019 have faced justice, even though PAS promised a “big purge” of the state apparatus. In addition, PAS’s image has been tarnished by scandals in which lucrative tenders were won by relatives of PAS deputies.

The government’s failure to make public administration more efficient as promised is not limited to corruption, as illustrated by a recent scandal over a prisoner amnesty that accidentally freed murderers sentenced to life imprisonment, despite undergoing approval from multiple agencies and passage through parliament. There have also been issues with the independence of the judiciary. The government has packed the Constitutional Court with former PAS members.

The economy is an even more sensitive issue. According to the National Bureau of Statistics, economic growth in 2024 was just 0.1 percent, while the absolute poverty rate rose from 31.6 percent to 33.6 percent. And the situation in the agricultural sector is worrying, with angry farmers regularly protesting in central Chișinău.

The government has claimed the economic statistics don’t reflect reality, but experts beg to differ. “The economic stagnation of 2024 … is a symptom of a much more serious problem,” Veaceslav Ioniță, an expert at the Viitorul Institute for Development and Social Initiatives, wrote in March. “Over the last five years, total economic growth has been just 0.4 percent—a level that is only comparable with the period immediately following the collapse of the Soviet Union.”

Of course, Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine goes a long way toward explaining the economic stagnation. Supply chains were upended in 2022, and Moldovan producers were deprived of traditional markets in neighboring Ukraine. However, with the war now in its fourth year, those using the fighting as the sole explanation for a lackluster economy are less and less convincing.

Nor has the Moldovan government been in a hurry to seize the opportunities presented by the war to address the long-running conflict with the breakaway region of Transnistria. Given that Transnistria’s main backer, Russia, is bogged down in Ukraine, Chișinău could exert unprecedented levels of pressure on the separatists. But that has not happened—nor is a solution to the problem any closer.

If anything, it is further away than ever, as negotiations on the settlement of the conflict have ceased. Moldovan officials say that the priority is not reintegration with Transnistria, but integration with Europe—and they cite the case of Cyprus to claim Moldova could join the EU with the Transnistria issue unresolved.

Amid mounting domestic problems, foreign policy is a more comfortable topic of conversation for Chișinău. Indeed, the Moldovan government managed to secure substantial financial as well as political support from Brussels. This year, the EU handed over €1.9 billion ($2.2 billion) in financial assistance (admittedly, €1.5 billion of that was loans that will need to be repaid).

The EU’s thinking isn’t hard to guess. If PAS loses in the September elections, this will not only cancel out all the benefits of Sandu’s presidential win last year, but also mean the bloc is obliged to forge an entirely new relationship with Chișinău. That would be particularly difficult if pro-Russian parties come to power. In other words, Brussels would prefer not to see a change of government. PAS is a good fit for European officials: the party supports Ukraine, is in conflict with Moscow, and does not cause the EU geopolitical problems.

Inevitably, though, the EU’s approach also has a downside. Support for a single party means the EU’s reputation is increasingly tied—at least in the eyes of Moldovans—to the fate of PAS. Brussels made this same mistake in the 2010s when it supported the Alliance for European Integration, and then Plahotniuc. That badly damaged the image of the EU among Moldovans. The rule of the ostensibly pro-Europe but deeply corrupt Alliance for European Integration led to support for joining the EU falling to a historic low. In 2015, just 39.5 percent of Moldovans were in favor of EU membership, while 41.8 percent were against.

Nevertheless, the EU has so many problems to deal with at the moment that it is unlikely to have time for this sort of analysis of past mistakes. Given that the Kremlin continues to wage war in Ukraine and is prepared to openly meddle in Moldovan politics to an unprecedented degree, the priority for Brussels is that pro-Europe parties remain in power in Chișinău.

At the same time, Russia’s support for politicians like Șor means that the PAS government can easily try to portray itself as a vital shield against Russian expansionism—and the least bad option on the ballot papers. If the vote ends up being cast as an existential struggle between Russia and Europe, Moldova’s economic data and living standards will be of secondary importance.