Russian President Vladimir Putin’s warm welcome in China this week for a Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) summit of twenty world leaders followed by a parade marking the end of World War II in Asia made for a sharp contrast with his reception at the G20 summit that took place in Brisbane, Australia in November 2014—during the first phase of Russia’s war against Ukraine.

Back then, it wasn’t only Western leaders who followed then U.S. president Barack Obama’s example and gave Putin the cold shoulder. Even China’s Xi Jinping spent more time with Obama than with Putin. The use of force to move a neighboring country’s borders and the shooting down of a civilian aircraft with a combat missile had not been seen for a long time: not just in the West, but in the Global South either. Putin left the G20 summit early, without waiting for the final statements and documents.

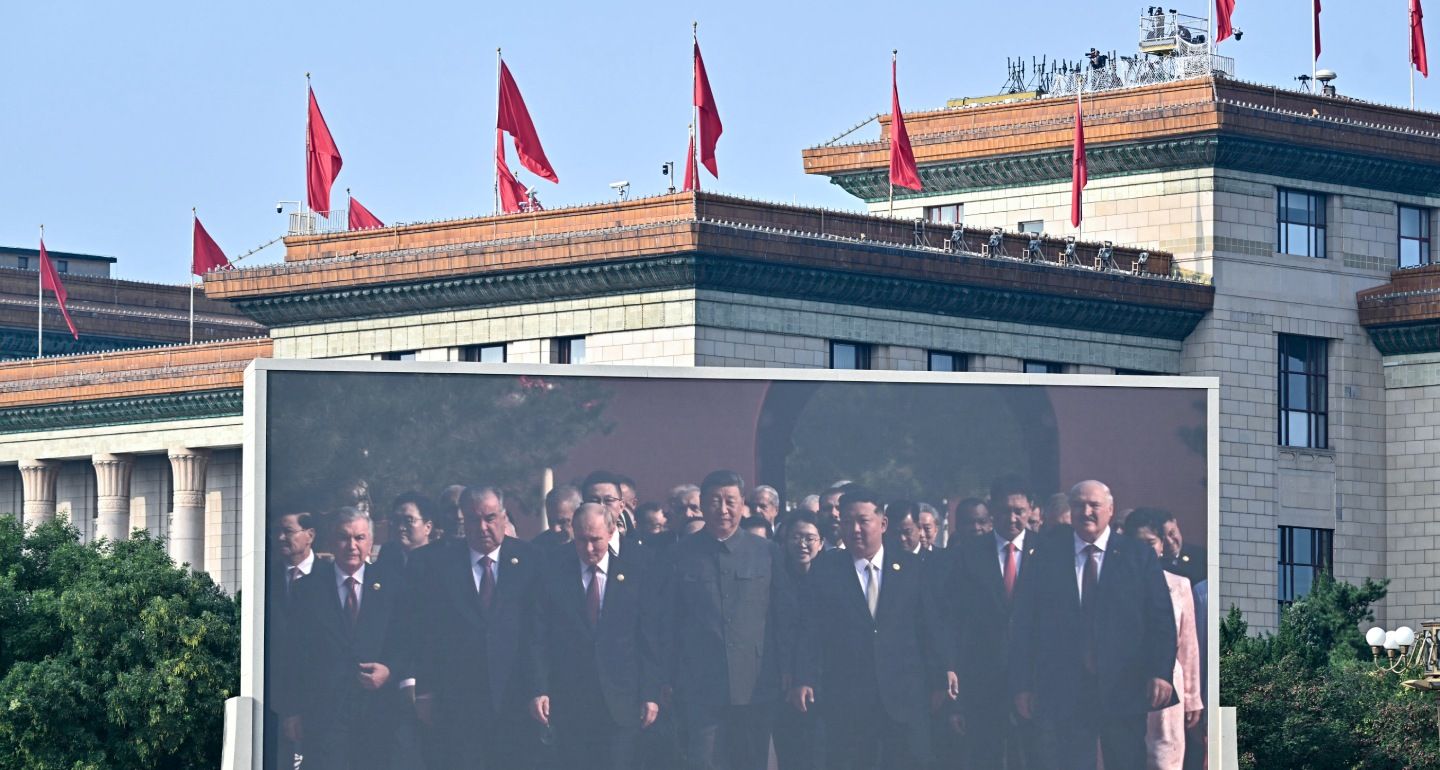

Compared with that summit, Putin’s position today looks like an unmitigated diplomatic triumph. He is still waging war against Ukraine, only that war is now incomparably more brutal, and quite openly so. Yet instead of a shortened stay, Putin embarked on an unprecedented four-day visit.

This time, too, it was the U.S. leader who set the tone for Putin’s welcome by rolling out the red carpet for him in Alaska last month to discuss an end to Russia’s war against Ukraine. But Donald Trump himself was conspicuously absent from the parade marking the end of World War II in Asia—even though he was at pains to publicly point out that his country had been instrumental in ending that war. His absence only reinforced the Kremlin’s narrative that it is not Russia that is isolated, but the West: the center of the world has shifted to the South and East, along with global economic growth and the global majority.

The situation was further aggravated by Trump’s undiplomatic comments on social media, in which he called on Xi to “Please give my warmest regards to Vladimir Putin, and [North Korean leader] Kim Jong Un, as you conspire against the United States of America.” The U.S. president sounded distinctly like an offended teen who had not been invited to the birthday party of the popular boy or girl in the class, and only highlighted the ambiguity of Trump’s position: did he refuse to go, or was he not invited?

Putin’s photo sessions from China look like a natural continuation of his photos from Alaska, turning those earlier images against Trump. The Alaska summit no longer looks like a manifestation of Washington’s goodwill, but more like confirmation that nothing can be decided without the Russian leader, while Putin and his friends are doing just fine without Trump.

A personal meeting is one of the important resources that U.S. presidents possess, and it is increasingly obvious that this resource was squandered in Alaska—and may even have made matters worse. Of course, this isn’t the first time that the United States has adopted a softer stance on dictators than the Europeans. This was justified by the fact that Washington has long borne disproportionately more practical responsibility for global security. During Francisco Franco’s forty years in power in Spain, not a single European democratic leader met with him, but he was visited by two U.S. presidents: Dwight Eisenhower and Richard Nixon.

Crucially, however, the result of their visits was not just to lend the dictator international legitimacy, but to achieve certain demands. Eisenhower’s military agreement with Franco didn’t just bring Spain into the Western security system; it also forced the regime to accept new economic rules that ultimately hastened the end of the dictatorship. Similarly, Nixon’s visit to the decrepit Franco and his young successor strengthened the latter’s position and helped in the dismantling of the regime.

There is no such visible result from the Alaska meeting. Trump spent a valuable diplomatic asset without influencing Putin in any way. On the contrary: it was Trump who changed his position in line with the Kremlin’s during the meeting. Before the summit in Anchorage, Trump was insisting on a ceasefire in Ukraine. Afterward, it had apparently ceased to matter.

Now the Kremlin and the White House claim to be moving directly toward a comprehensive peace agreement—but in parallel with the ongoing fighting, just as the Kremlin had wanted. And since Moscow is insisting on including a vast range of topics in any peace agreement, that gives Russia unlimited time to keep waging war in Ukraine. To top it all off, Putin did not even reduce the intensity of the bombing of Ukrainian cities as a gesture of gratitude to Trump for hosting the meeting. On the contrary, he has only ramped it up.

Putin’s successful trip to China made it clear that the main justification for Trump's rapprochement with Putin is a myth. The U.S. president has failed to divide Russia and China.

In the process of giving away a diplomatic asset to Putin, Trump also sacrificed an important achievement of U.S. diplomacy in recent years: the rapprochement with India. For many years prior to that achievement between the world’s two biggest democracies, India was closer to Moscow than to Washington, which in turn supported Pakistan, which was constantly sliding into dictatorship.

The situation began to change at the beginning of this century. Relations between the two democracies developed into partnerships, and amid the growing alliance between Beijing and Moscow, India was perceived as a relatively weak link in the new non-Western and anti-Western international structures.

Following his talks with Putin, Trump declined to make good on a threat to introduce yet more sanctions against Russia. But he did slap an additional 25 percent tariff on Indian exports to the United States over New Delhi’s purchases of Russian oil, bringing tariffs up to 50 percent. The tariffs came into force on August 27 and were sharply criticized by the Indian leadership. By August 31, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi—who had not visited China once in the previous seven years—was at the SCO summit in Tianjin, rubbing shoulders with Xi and Putin.

Any hopes Trump may have had of forming an alliance against China can be written off. Even the sight of Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky meeting with Ukraine’s allies at a European summit in Paris on September 4 couldn’t eclipse the visuals from Putin’s trip to China. The celebrations in China were attended by defectors from the Western camp—Hungary’s Viktor Orban and Slovakia’s Robert Fico—while it’s impossible now to imagine representatives of the Global South at European meetings in support of Ukraine, even from among the minority shareholders. Indeed, why should they bother when even the United States is distancing itself from support for the besieged country?

The opportunity to outweigh the current impression of Putin’s diplomatic tour de force will only come in November, when Johannesburg hosts the G20 summit. Putin may not attend for a combination of legal reasons (South Africa is a member of the International Criminal Court, which has issued an arrest warrant for Putin on charges of war crimes) and security considerations: since the full-scale invasion, he has avoided flying over large swathes of international waters and countries. But even if the Russian leader is not at the summit, and especially if he is there, after the Chinese celebrations it will be Trump, not Putin, who has to try to win over other attendees and prove that he is not the one facing international isolation—including by seeking photo opportunities and verbal support from Putin, Modi, and Xi.