The evening of September 20 saw Moscow host a revival of the Soviet-era Intervision song contest, which was established during the Cold War as a socialist bloc alternative to Eurovision, and took place for the last time in Poland in 1980. Russian President Vladimir Putin first suggested bringing back Intervision in 2009, but it took Russia’s exclusion from Eurovision following the full-scale invasion of Ukraine to make it a reality. The relaunch had a big budget and featured a line-up of world-class performers, but neither money nor show business wizardry could conceal the political baggage of modern Russia.

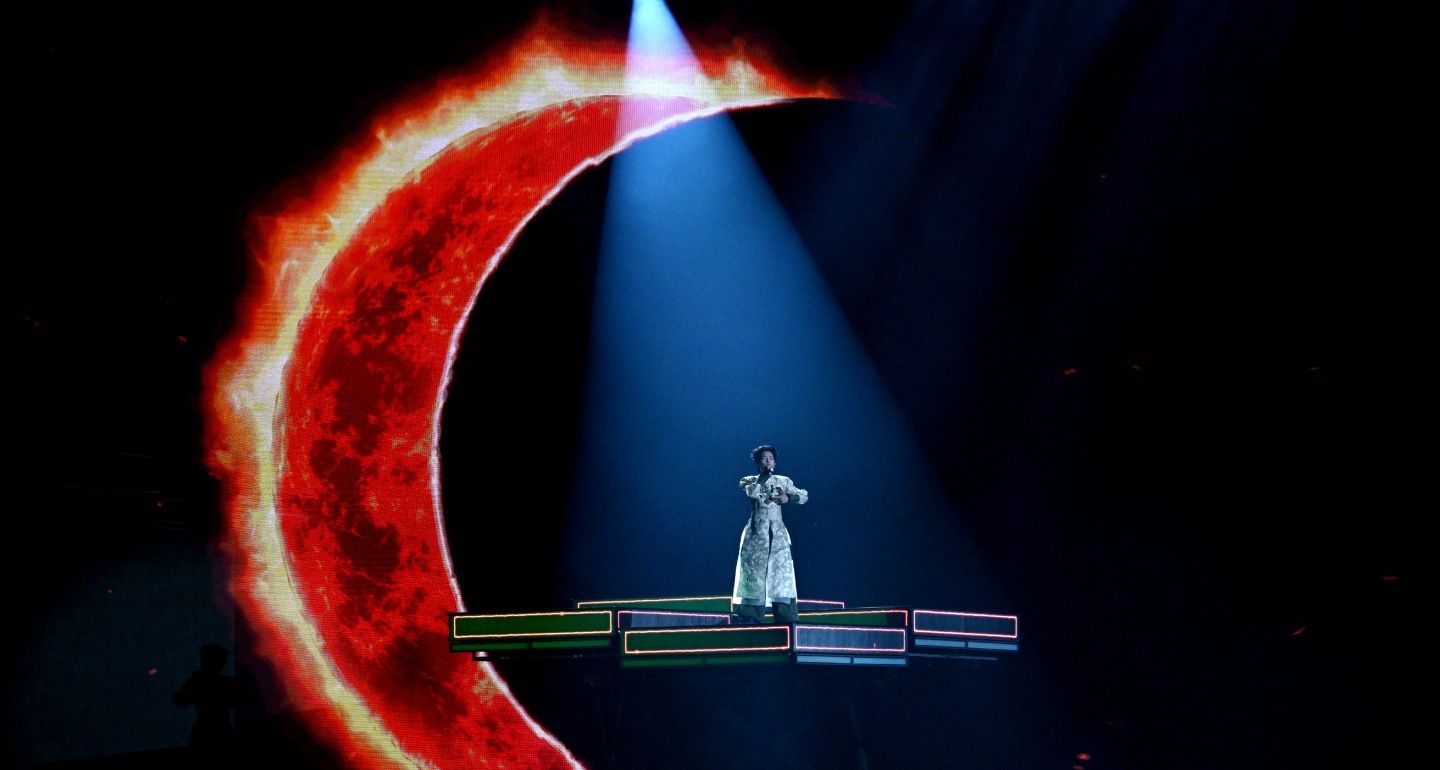

In some ways—not least, geographical scope—Intervision was at least as ambitious as its Western counterpart. Performers from twenty-three countries took part, from Belarus, Tajikistan, and Serbia to Vietnam, Cuba, Brazil, and South Africa. The lighting, sound, introductory videos, animations, augmented reality sections, and laser effects were all of a high standard, too.

Perhaps most significantly, the event managed to defy expectations about being overtly political: there was no aggressive, pro-war propaganda, and no authoritarian-militaristic aesthetic in the style of the 1936 Berlin Olympics. Nor was there much Slavic kitsch. Putin’s video address was just three minutes long. All in all, the organizers bent over backwards to project a version of modern Russia sanitized for foreign export—similar to the 2014 Sochi Winter Olympics.

Still, none of that saved the event from the intrusion of political reality. The idea for the revived Intervision was that it should differ from a commercialized Eurovision by showcasing respect for national traditions. In practice, this had an impact on the music itself. Eurovision usually generates a few hits, but the songs at Intervision will only be remembered by the most hardcore fans.

The ideological messaging was also confused. Eurovision was originally set up to promote pacifism, European integration, and dialogue through music. From the 1980s it also became a symbol of diversity, inclusivity, and tolerance. The modern-day incarnation of Intervision was very different. Since Russia jails people for “LGBT extremism,” celebrating diversity in the Eurovision sense was hardly an option. Instead, organizers sought to stress a variety of musical traditions. But they tried too hard, and what was supposed to be a music contest ended up looking and sounding more like an ethnographic festival.

The absence of audience voting meant Intervision could have been much shorter than Eurovision, which usually lasts about four hours. But Intervision’s organizers—as if they felt putting on a shorter event would be a failure—made sure they also hit the four-hour mark. That necessitated adding up to five minutes of talk (mostly banal facts about the countries being represented) for every three minutes of singing. The excessively formal language of the Russian presenters evoked the atmosphere of the post-war Soviet Union of Putin’s youth.

The organizers particularly struggled with how to manage LGBT issues. The entry from the United States, Vassy, pulled out at the last minute. While the presenters said this was because of political pressure from her home country, Australia, leaks to the media suggested she was barred because of fears she would express support for Russia’s embattled LGBT community from the stage.

In the end, attempts to avoid LGBT issues proved fruitless: it emerged after the competition that the winner—Vietnamese singer Duc Phuc—is openly gay and has released music videos with explicitly gay themes.

While Intervision was marketed as distinct to Eurovision, the truth is that—from the name to the duration, the choice of presenters, the design of the trophies, and the style of the graphics used in the television broadcast—it was very similar.

The event’s main problem, though, was not its lack of originality, but that it didn’t manage to provide a convincing answer as to why it was even necessary in the first place. Intervision during the Cold War was a straightforward riposte to Eurovision—just as Comecon (the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance) was the Soviet answer to the U.S. Marshall Plan. But modern Russia is not a superpower in a bipolar world.

Instead, modern Intervision seemed to have been conceived as an accompaniment to Putin’s attempts to woo the Global South following the full-scale invasion of Ukraine. The organizers, however, did not get the memo.

If Intervision was intended to promote Moscow’s supposed message of peace, then why was so little spent on promotion? Why, for example, did the official YouTube livestream of Intervision in India—a country of 1.4 billion people—get just 231,000 views? And if the performers were all supposed to be famous pop stars in their home countries, why did the Ethiopian entry, Netsanet Sultan, have fewer than a thousand followers on Instagram?

There was also a telling controversy about viewing figures. While organizers initially claimed 4 billion people watched the event, they were forced to backtrack amid ridicule (that number was actually the total population of the countries showing Intervision). The broadcast on Russian social media platform VK was watched live by no more than 60,000 people—although organizers said the final figure was 10 million. If Intervision was supposed to be a homegrown alternative to Eurovision, then those viewing figures were disappointing: in 2021—the last year before the full-scale invasion of Ukraine—28.5 million Russians watched Eurovision.

According to eyewitness testimony, people in Moscow were being offered 6,000 rubles ($72) to attend Intervision on the night—an apparent attempt to boost audience numbers. And, in time-honored Soviet traditions, students from Moscow’s Peoples’ Friendship University were bussed in to pretend to be foreigners who had traveled to Russia for the occasion. Revealingly, the Moscow authorities did not deem Intervision to be well-attended enough to extend subway opening hours, which is normal practice for big events in the capital.

Russian television is increasingly required to devote more time to ideological cliches to please the country’s ageing, nostalgic leader. And even the most talented entertainment executives struggle to make Kremlin requests—like Intervision—into compelling viewing. After all, no amount of technical skill can mask confusion about your audience, or the paralyzing fear of making a mistake.