In the wake of mounting public backlash against its growing influence in Central Asia, China is betting on vocational education to reshape perceptions and re‑anchor its presence in the region. At a September 2025 meeting between Chinese leader Xi Jinping and Kazakh President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev, the pair announced the opening of two new Luban Workshops in the Central Asian country.

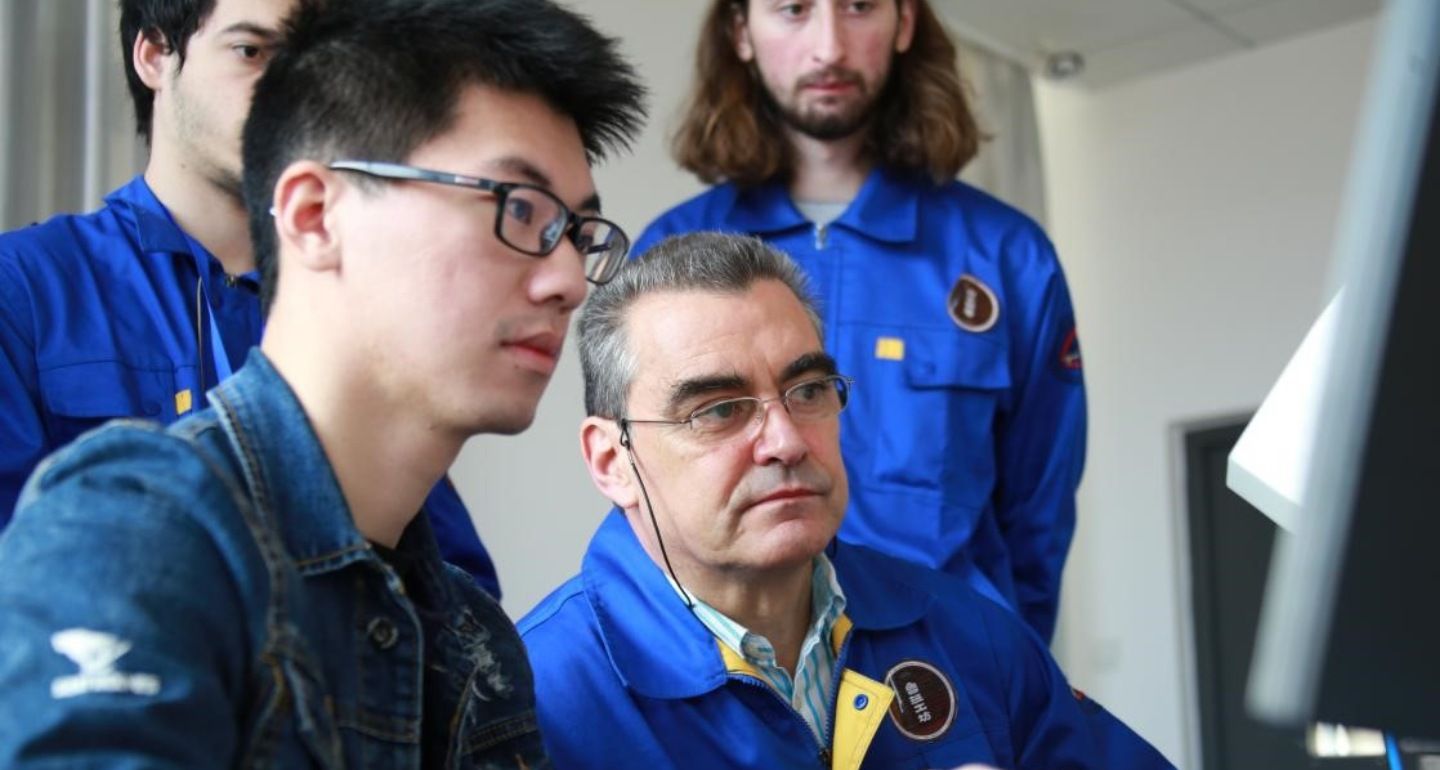

Over the past two years, Beijing has launched a flurry of these technical training centers (named after a legendary Chinese craftsman) in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan. While much of Beijing’s engagement with the region has focused on the extraction of critical minerals and energy resources and construction of infrastructure, the Luban initiative, spearheaded by the Tianjin municipality, is a marked shift: an effort to win hearts and minds by equipping local youth with high‑demand skills in AI, logistics, electric vehicle maintenance, hydropower, and automation, which helps Central Asia move up the value chain.

This push is as strategic as it is philanthropic. First launched in 2016, the Luban Workshop network is part of China’s global strategy to improve its image while serving its economic interests by promoting its technologies. In Central Asia, where Sinophobia has surged in recent years amid protests over land rights, debt diplomacy, and China’s treatment of Turkic Muslims in Xinjiang, the stakes surrounding China’s image are unusually high.

The Luban Workshops represent an attempt to recast China not as a threat, but as a pragmatic partner in human capital development: a partner offering in-demand skills, opportunity, and advancement. They form a vital component of the Belt and Road Initiative’s long‑overlooked people‑to‑people exchange pillar and may offer Beijing one of its most credible soft‑power tools in a region where goodwill has proved elusive. Xi is a strong advocate for the initiative, recently calling for its expansion.

The scale and speed of the rollout is telling. In Kazakhstan alone, where anti‑China protests have become a near‑annual occurrence since 2016, Beijing has unveiled three Luban Workshops since 2023, with two more under construction. Each of these centers is tailored to the host country’s priorities, allowing China to demonstrate responsiveness to local needs in contrast to Western donors, which it frames as imposing their own interests and priorities.

These include workshops on AI at the L.N. Gumilyov Eurasian National University in Astana, on electric vehicle systems in Almaty, and on logistics and transport at East Kazakhstan Technical University. President Tokayev has publicly praised the program, calling the workshops “exemplary” and urging China to build more.

In neighboring Kyrgyzstan, the new Luban Workshop in Bishkek focuses on hydropower and road construction, addressing national development bottlenecks. In Tashkent, the Uzbek iteration supports the government’s “Digital Uzbekistan‑2030” strategy. And in Dushanbe, where China launched the region’s first Luban Workshop in 2022, more than 1,500 students have already attended courses on surveying and urban infrastructure.

A further workshop is planned at the Yagshygeldi Kakayev International Oil and Gas University in Turkmenistan. Unsurprisingly, given that China accounts for over half of Turkmenistan’s gas exports, it will focus on energy.

Unlike the earlier wave of Confucius Institutes, which faced criticism for pushing Chinese state narratives rather than addressing practical concerns, the Luban Workshops offer tangible value: certified skills in fields that matter to local economies. They create pathways for young Central Asians to participate in high‑tech sectors that are otherwise dominated by foreign labor, and they subtly acclimate them to Chinese technological standards, tools, and educational norms.

This effort comes at a time when Beijing urgently needs to stem reputational damage. From 2018 to 2020 alone, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan witnessed dozens of protests over Chinese mining operations, environmental degradation, and fears of permanent land transfers to Chinese investors. Some protests turned violent, others forced multi‑million‑dollar projects to be canceled altogether. The backlash was not confined to fringe nationalist groups: many demonstrations included workers, students, and civic organizations disillusioned with the opacity and extractive nature of Chinese investment.

The Luban Workshops aim to convert resentment into cooperation by shifting the public focus from controversial megaprojects to human development and higher-value investments. In doing so, they also address one of the most common complaints about Chinese investment globally: overreliance on Chinese labor. By building up the local workforce, the workshops give China a more sustainable model of engagement. They also generate constituencies: students, administrators, and mid‑level government officials who have benefited directly from Chinese training and are more likely to view the relationship favorably.

But there are trade‑offs. For all the goodwill they generate, the workshops also deepen dependency. Most are designed and operated by Chinese institutions, using Chinese equipment and software. In Kazakhstan, for instance, the electric vehicle curriculum is supplied almost entirely by Tianjin Vocational Institute, and Chinese technicians train both faculty and students. In effect, they lay the groundwork for a China‑centric technical ecosystem in which Chinese companies, equipment, and standards become deeply embedded in national development strategies. This raises questions about long‑term autonomy, especially if the training fails to evolve with local needs.

Still, in the near term, Luban Workshops appear to be working, not only as instruments of technical education, but also as vessels of image repair. By shifting its pitch from “China the builder” to “China the trainer,” Beijing has found a way to present itself as a stakeholder in human development rather than merely a pursuer of strategic interests. And for Central Asian governments, grappling with youth unemployment, infrastructure deficits, and technology gaps, the appeal of such programs is hard to resist.

More broadly, China’s embrace of vocational diplomacy reflects a subtle recalibration of its global engagement. Luban Workshops embody a quieter logic of influence built on relationships, institutions, and long‑term social capital. Whether this approach can reverse the tide of Sinophobia or insulate China from future protest movements remains to be seen. What is clear, however, is that Beijing is learning to adapt. The era of raw economic assertiveness is giving way to a more nuanced strategy that fuses investment with education, infrastructure with human capital, and ambition with a dose of humility. In the contested arena of Central Asia, such recalibrations may prove decisive.