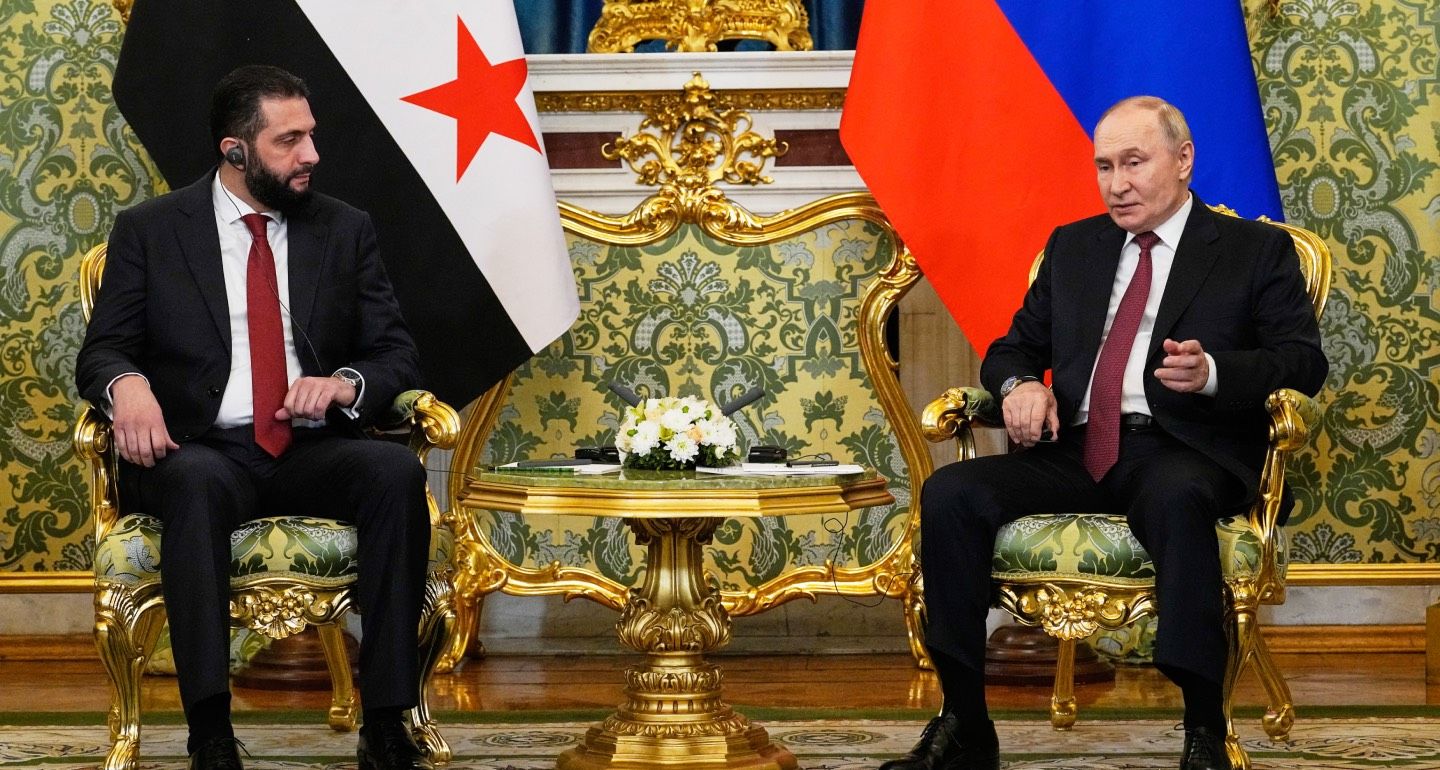

The arrival in Moscow on October 15 of the new Syrian leader Ahmad al-Sharaa, a former al-Qaeda militant who was hunted by the Russian military for years, marked a new turning point in Russian-Syrian relations. This unexpected rapprochement is driven by mutual interest.

The new Syrian leadership needs to strengthen its own legitimacy and address economic and security problems that Moscow can help to alleviate. For Russian President Vladimir Putin, the meeting with al-Sharaa was an opportunity to save face after the fall of the Assad regime, on whose side Russia had fought for a decade, and to demonstrate that Russia still has a presence in the Middle East. So far, the fact that Syria’s fugitive former president Bashar al-Assad has found refuge in the Russian capital has not become an irritant in relations between Moscow and Damascus.

When the Russian air force launched its operation in Syria a decade ago in support of the ruling regime, one of its main goals was to combat militants from Jabhat al-Nusra (Al-Nusra Front), a terrorist group aligned with the Islamic State and led by al-Sharaa, who had come up through the ranks of al-Qaeda.

It was at Moscow’s insistence that Jabhat al-Nusra was included on the UN Security Council’s list of terrorists. The group’s subsequent name changes and public severing of ties with al-Qaeda did not alter Russia’s position. It remains banned by the Russian authorities, who continue to arrest people suspected of having ties to the organization.

However, the rapid seizure of power in Syria by armed rebels and the fall of Assad’s regime late last year forced Moscow to come to terms with the new reality. Almost immediately, Russia established contact with the new Syrian authorities, who, in turn, declared that they were giving Moscow “the opportunity to reconsider its relations with the Syrian people.”

By the end of January this year, the first visit of a Russian delegation to Syria since Assad’s overthrow took place, led by Deputy Foreign Minister Mikhail Bogdanov. Two weeks later, Putin held a telephone conversation with al-Sharaa, who had proclaimed himself president. Both sides have a vested interest in strengthening their cooperation, and the Syrian president’s talks with Putin in the Kremlin were aimed at agreeing the main areas of this cooperation.

For al-Sharaa, who just a year ago was a target for Russian troops, with the United States offering $10 million for information on his whereabouts, any international contacts and trips abroad are an opportunity to emphasize his legitimacy.

For Putin, meanwhile, the meeting with the new Syrian leader, whose authority is already recognized by most countries in the region, is a chance to save face and show that Russia, unlike Iran, has not lost in Syria. More broadly, the Kremlin is emphasizing that Russia’s position in the Middle East is unshakable, despite the reduction of its military presence in Syria.

The number one concern for the Damascus authorities right now is security. Yesterday’s jihadists have not only been unable so far to maintain order on the ground, they are becoming directly involved in conflicts with local communities, such as the Alawites in western Syria in early March, when at least 1,500 civilians were killed, and the Druze in the south of the country in late April and July.

To stabilize the situation, Syria’s new rulers are prepared to deploy Russian military patrols in certain regions of the country. During the talks in the Kremlin, al-Sharaa reportedly asked Putin to return Russian troops to southern Syria.

As well as providing security, Russian military forces could potentially serve as a counterweight to the Israeli presence in the south of the Arab Republic. The mere presence of Russian military personnel in the country would force the Israeli leadership to exercise greater restraint when launching strikes against Syrian territory.

The Russian contingent also helps Damascus to balance the influence of Turkey, which has bases in northern Syria and plans to expand its military presence in the Arab Republic.

Another headache for the new Syrian authorities remains the unresolved issue of Kurdish armed groups, which still control up to 30 percent of the north and northeast of the country and refuse to integrate into the Syrian army. Russia, which has long-established contacts with the Syrian Kurds and offered integration options to them even under Assad, could act as a mediator between them and Damascus.

Syrian Kurdistan has even had a representative office in Moscow since 2016. For Al-Sharaa, negotiations would be preferable to conducting a military operation against the Kurds—something Ankara has been pushing for recently. The Kurds themselves may also be interested in having Russian patronage, given their U.S. allies’ plans to significantly reduce their military presence in eastern Syria now that Donald Trump is back in the White House.

Russia itself retains two military facilities in Syria for which the 2017 lease agreement lasts through 2066: a naval base in the port city of Tartus and the Khmeimim air base in Latakia, which currently serve as logistical hubs for Russia’s growing operations in Africa. The new Syrian leader has made a point of emphasizing that the republic’s authorities respect “all previously signed agreements between Moscow and Damascus.”

According to estimates by the new Syrian government, rebuilding the country after thirteen years of civil war will cost about $900 billion. Russia is neither willing nor able to invest billions of dollars in Syria’s infrastructure and economy, but had earlier said it was prepared to cooperate in specific areas, such as the restoration of the energy and humanitarian aid sectors. Following the talks between Putin and al-Sharaa, Russia agreed to consider supplying Syria with wheat, medicine, and food, as well as to work on the country’s oil fields.

In addition, Moscow and Damascus are set to hold a meeting of the intergovernmental commission on developing trade and economic cooperation. Meanwhile, the Russian company Gosznak, which printed Syrian currency under Assad, is expected to issue new banknotes to replace the current ones featuring portraits of the ousted dictator.

The fate of Assad, who has been granted asylum in Moscow, is another issue that Moscow and Damascus will eventually have to discuss. The deposed dictator is wanted in Syria for the use of violence against his own people, but the new authorities have not yet officially asked Moscow to extradite him. The Russian government, for its part, has ensured that Assad keeps a low profile and does not appear in public or give interviews.

So far, the fugitive former president has not proved a major obstacle to the development of relations between Moscow and Damascus, and is unlikely to do so. Syria’s new leaders have more pressing concerns, such as holding onto power and restoring order in the war-torn country. As long as Moscow is willing to assist them in those tasks, more delicate issues such as Assad’s fate can take a back seat.