Nadia Leila Aissaoui | Algerian-French sociologist

There is a growing conviction in Algeria and in most Arab countries today that a majority of Western actors—Europeans, Americans, or Russians—are opposed for different reasons to political change that could threaten existing regimes, even if they don’t declare it.

What is specific to President Donald Trump however, is that unlike Europeans and former U.S. presidents who evoked democracy and human rights in their speeches and sometime took them into consideration when dealing with specific questions, he has no problems declaring his support for despotic regimes. In that sense he is closer to Russian positions in the Middle East than to traditional “declared” Western ones, that used to condition support on some reforms or human rights improvements.

However, people are not frightened anymore when they know that Trump supports the regime against which they are rising. This applies to Algeria, and I think also Sudan. With millions of people in the streets on a weekly basis, a new sense of the balance of power is evolving, and Trump’s positions don’t seem to affect this much. That is of course for as long as the confrontations remain peaceful. In the case of violent confrontations, as in Libya in 2011, the calculations are different due to the need for weapons supplies and United Nations Security Council resolutions, or the blocking of such resolutions.

Amy Hawthorne | Deputy director of research at the Project on Middle East Democracy

Arab autocrats need more than Donald Trump’s endorsement to remain in power. Like authoritarians elsewhere, they rely mostly on domestic tools. These include control over the military and police to crush dissent; over media and the education system to shape public opinion; and over state resources to fund corruption networks. They also know how to exploit security threats and societal divisions to justify the need for “order,” and to inculcate sufficient fear, or apathy, to deter most citizens from rising up. Nonetheless, backing from the U.S. president is a valuable extra, bringing dictators global legitimacy and diplomatic breathing space, international financing, and weapons that can allow them to outlast their natural shelf life.

Americans who see Trump’s blunt and unapologetic backing of autocratic allies, such as Saudi Arabia’s Mohammed bin Salman, as a shocking departure haven’t been paying enough attention to the U.S. role in the Arab world. Beneath Trump’s jarring style, his administration’s policies toward Arab autocratic allies are in line with those of every White House since the Cold War. Trump’s recent predecessors might have crafted loftier rhetoric to justify putting security interests ahead of democratic values, held their noses when endorsing dictators, or even occasionally raised human rights concerns—at the margins. But like Trump, they kept political, economic, and security support for pro-American strongmen flowing, with no real democracy strings attached. This support contributed to the longevity of their regimes. The crudeness of Trump’s approach aside, his administration is continuing, not breaking with, a long U.S. tradition in the Middle East.

Amr Hamzawy | Senior research scholar at the Center on Democracy, Development, and the Rule of Law in the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies at Stanford University

My answer is a provocative “no.”

The persistence of despotism and the failure of democratic transitions in several Arab countries are the outcome of domestic causes. In Saudi Arabia and Egypt, Arab citizens have been deprived of their freedom either because repressive state institutions have kept them in check or because the fear of instability and the threat of civil war have led them to favor despotism over chaotic democratic transitions.

In Syria, what began in 2011 as a democratic uprising quickly slipped into an ugly civil war in the face of the Assad regime’s brutality and the comparable brutality of terrorist groups. The endorsement of Arab despots by U.S. administrations (in Saudi Arabia and Egypt) or the lack thereof (as in Syria) did not change the mostly tragic course of events. Executions of regime opponents in Saudi Arabia happened during both the Obama and Trump administrations, amid Barack Obama’s disapproval and Donald Trump’s acquiescence. The regime of Abdel-Fattah al-Sisi in Egypt passed undemocratic laws, as well as constitutional amendments, both during the Obama years and under the supportive eyes of the Trump administration. In Syria, neither the Obama warning against the regime’s use of chemical weapons nor the announced plan of the Trump administration to withdraw American troops significantly impacted the fate of Syrians.

In other cases, as demonstrated most recently by the protests in Algeria and Sudan, the endorsement of Arab despots by U.S. administrations did not prevent their being removed from power. By the same token, the survival of the Tunisian democratic experiment that began in 2011 is related to domestic factors and has defied a hostile regional environment and indifferent international actors, including the lukewarm position of the United States.

Arab political realities are local phenomena driven by domestic factors. External factors, including American policies, are of secondary importance. This reality applies to President Donald Trump’s endorsement of Arab despots. Neither does he increase the despots’ persistence, nor can he prevent their fall when democratic uprisings shatter authoritarian stability.

Michele Dunne | Director and senior fellow in the Carnegie Middle East Program

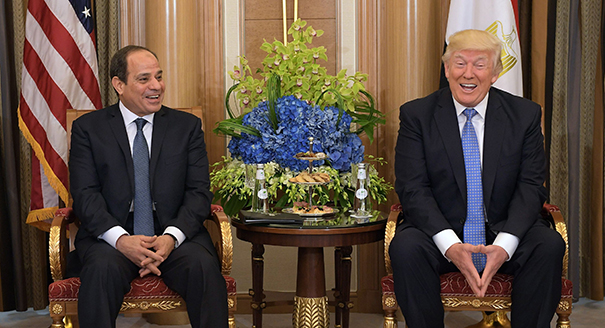

What the United States does in the Middle East is not always decisive, but it is always influential. Regarding support for Arab despots, President Donald Trump’s shielding of Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman from blame for the brutal murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi does not clean the prince in the eyes of anyone, but for now it has paved the way for major international business figures to resume dealings with him. Trump’s hosting of Egyptian President Abdel-Fattah al-Sisi just before a popular referendum on constitutional amendments to keep him in power for years probably did help silence some critics within the Egyptian elite. However, it will not count for anything if the Egyptian public someday decides that it is fed up with Sisi.

What Trump is doing through such actions is spending political capital profligately and surrendering U.S. soft power by the bucketful—apparently without getting much in return. Sisi has already bailed out of Trump’s Middle East Strategic Alliance—a security alliance of Arab states designed to help counter Iran—and neither Sisi nor Mohammed bin Salman is likely to do much to support Trump’s peace deal for Israelis and Palestinians when it finally emerges.