The organization is under U.S. sanctions, caught between a need to change and a refusal to do so.

Mohamad Fawaz

{

"authors": [

"Jake Sullivan",

"Kurt M. Campbell"

],

"type": "legacyinthemedia",

"centerAffiliationAll": "dc",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace"

],

"collections": [],

"englishNewsletterAll": "americanStatecraft",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"programAffiliation": "ASP",

"programs": [

"American Statecraft"

],

"projects": [],

"regions": [

"North America",

"United States",

"East Asia",

"China"

],

"topics": [

"Foreign Policy"

]

}

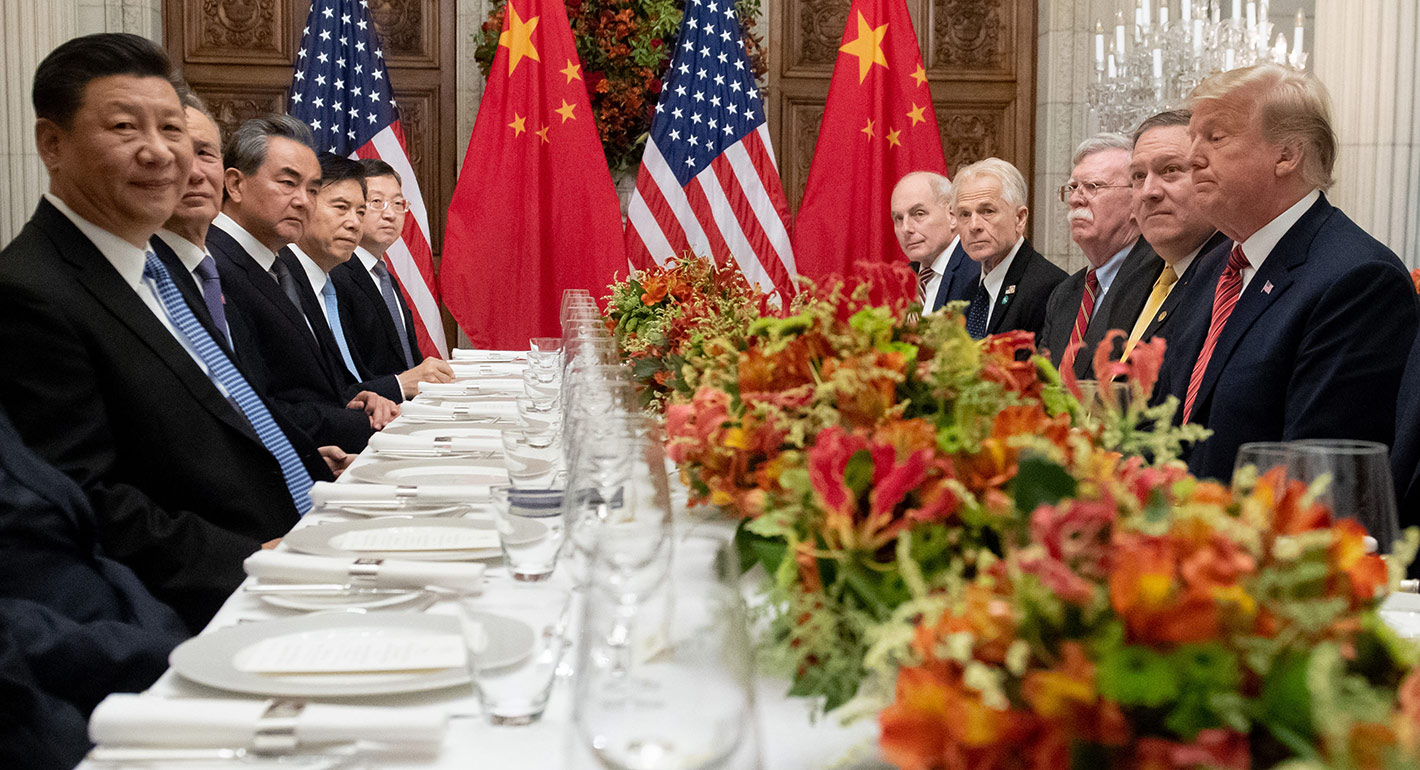

Source: Getty

The United States is in the midst of the most consequential rethinking of its foreign policy since the end of the Cold War. Although Washington remains bitterly divided on most issues, there is a growing consensus that the era of engagement with China has come to an unceremonious close.

Source: Foreign Affairs

The United States is in the midst of the most consequential rethinking of its foreign policy since the end of the Cold War. Although Washington remains bitterly divided on most issues, there is a growing consensus that the era of engagement with China has come to an unceremonious close. The debate now is over what comes next.

Like many debates throughout the history of U.S. foreign policy, this one has elements of both productive innovation and destructive demagoguery. Most observers can agree that, as the Trump administration’s National Security Strategy put it in 2018, “strategic competition” should animate the United States’ approach to Beijing going forward. But foreign policy frameworks beginning with the word “strategic” often raise more questions than they answer. “Strategic patience” reflects uncertainty about what to do and when. “Strategic ambiguity” reflects uncertainty about what to signal. And in this case, “strategic competition” reflects uncertainty about what that competition is over and what it means to win.

The rapid coalescence of a new consensus has left these essential questions about U.S.-Chinese competition unanswered. What, exactly, is the United States competing for? And what might a plausible desired outcome of this competition look like? A failure to connect competitive means to clear ends will allow U.S. policy to drift toward competition for competition’s sake and then fall into a dangerous cycle of confrontation....

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

The organization is under U.S. sanctions, caught between a need to change and a refusal to do so.

Mohamad Fawaz

A coalition of states is seeking to avert a U.S. attack, and Israel is in the forefront of their mind.

Michael Young

Implementing Phase 2 of Trump’s plan for the territory only makes sense if all in Phase 1 is implemented.

Yezid Sayigh

Israeli-Lebanese talks have stalled, and the reason is that the United States and Israel want to impose normalization.

Michael Young

Baku may allow radical nationalists to publicly discuss “reunification” with Azeri Iranians, but the president and key officials prefer not to comment publicly on the protests in Iran.

Bashir Kitachaev