Unexpectedly, Trump’s America appears to have replaced Putin’s Russia’s as the world’s biggest disruptor.

Alexander Baunov

{

"authors": [

"Maxim Starchak"

],

"type": "commentary",

"blog": "Carnegie Politika",

"centerAffiliationAll": "",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center"

],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center",

"programAffiliation": "",

"programs": [],

"projects": [],

"regions": [

"Russia"

],

"topics": [

"Nuclear Policy",

"Security",

"Arms Control"

]

}

Faced with the conditions of a real war, the defense industry’s priorities have shifted toward conventional forces.

For a long time, the driving force behind Russia’s rearmament was the modernization of its strategic nuclear forces, by retiring missiles and carriers developed in Soviet times and switching to new Russian technologies. In 2024, however, Russia’s nuclear forces stopped being updated. By the end of the year, President Vladimir Putin’s focus was on the new Oreshnik missile system and medium-range ballistic missile.

As of the end of last year, modern weapons (i.e., Russian rather than Soviet ones) made up 88 percent of the entire arsenal of Russia’s Strategic Missile Forces (SMF), according to Colonel General Sergei Karakayev, commander of the SMF. That proportion was exactly the same at the end of 2023. In other words, modernization has stalled, though it was previously due to be completed by the end of 2024.

The Defense Ministry has received all the Yars mobile intercontinental ballistic missile systems it was expecting, along with two regiments of Avangard missile systems, but the silo-based Yars missiles and Sarmat systems have not yet been fully deployed. The rearmament of the Kozelsk missile division with Yars systems is planned to be completed in 2025, while the deployment of the Sarmat for combat duty looks set to take several more years, despite the fact that the required infrastructure has been built in the Krasnoyarsk region and serial production of the missile has already been announced.

The delays primarily stem from the fact that the Roscosmos subsidiaries involved in the production of the Sarmat are experiencing financial and manufacturing problems due to sanctions, personnel shortages, and debt. The missile itself is also plagued by difficulties: of all five Sarmat launches, only one was successful.

The Sarmat is supposed to replace the Voevoda, a Ukrainian-produced Soviet missile system. The service life of the Voevoda was extended by five years back in 2013, but after Russia’s annexation of Crimea the following year and the beginning of the conflict in Donbas, the missile’s Ukrainian developers and manufacturers stopped interacting with Russia, meaning that Russia has not had a technically ready heavy intercontinental missile in service for about six years. Now the potential of both the old Voevoda and the new Sarmat to launch and hit a target remains in doubt.

Unsurprisingly, the Russian authorities made no mention of this in their statements last year. Instead, they paid a lot of attention to the medium-range hypersonic missile of which Putin is so fond: the Oreshnik, which was tested in combat conditions in November. The likely manufacturer of these missiles, the Votkinsk factory, is constructing five new buildings, modernizing twenty existing facilities, and looking for an additional 1,200 workers. It seems that Russia is actively preparing for the production of the Oreshnik and, accordingly, for its imminent deployment.

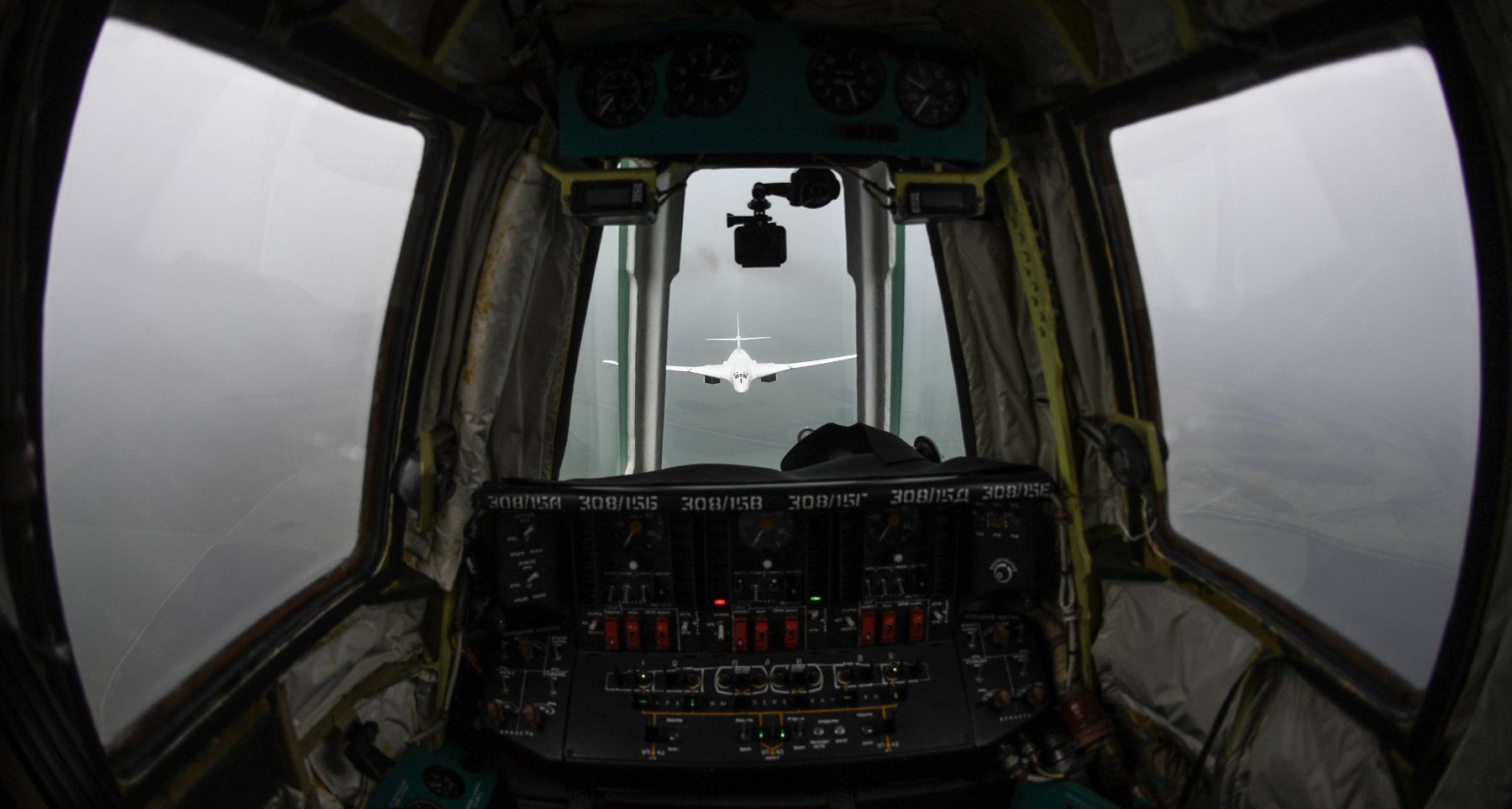

The state of the nuclear triad’s air component is no more straightforward. Russia’s then defense minister Sergei Shoigu announced that two additional Tu-160M strategic bombers would enter into service in 2024, but that never happened.

Two more Tu-160Ms are due to be delivered in 2025, but that does not look likely either. Two Tu-160Ms are currently undergoing factory testing, and there has been no information about the rollout of other aircraft or their testing so far.

The delays are understandable given that the Kazan aircraft plant, which produces the Tu-160M, has also been tasked with reviving the project of the Soviet-designed Tu-214 medium-range passenger aircraft. That second task prompted the repurposing of the workshop originally allocated for the production of the PAK DA stealth missile carrier for civilian requirements. The first prototype of the next-generation strategic stealth bomber was supposed to be out by 2022, and preliminary tests were planned for April 2023. None of those deadlines were met.

The program for the deep modernization of Tu-95MS strategic bombers (NATO classification: Bear-H) also turned out to be anything but easy. The program, launched in 2018, was supposed to cover up to thirty-five aircraft, including their navigation and information display systems, onboard defense systems, radars, and engines. A standout feature of the new version of the aircraft, called the Tu-95MSM, is the ability to carry Kh-101/102 missiles.

So far, the Defense Ministry has not received a single Tu-95MSM. Instead, it has had to make do with the partial replacement of equipment on the bombers. The problem is that deep modernization requires the latest equipment, which under sanctions is extremely difficult to buy abroad or develop independently.

The Sevmash plant, a key element in the modernization of the nuclear triad’s naval component, is also experiencing problems as a result of sanctions. Last summer, Sevmash CEO Andrei Puchkov and the commander in chief of the Russian navy, Admiral Alexander Moiseyev, said that the navy would receive the Knyaz Pozharsky (Borey-A project) strategic submarine by the end of 2024. As predicted last year, however, that did not happen. Now the planned date is June 2025. The start dates for the construction of two more submarines—the Borey-AM (955AM) modification, which requires additional time—are also constantly being postponed.

Sevmash has been unable to find a replacement for the foreign components in its submarines. The Trade and Industry Ministry organized tenders for the development of Russian-made components, but their implementation is only planned for 2028.

In addition to the Boreys, Russia also has strategic submarines belonging to the Soviet-designed Delfin (Dolphin) class. In November 2024, repairs were supposed to be completed on one of these—the Bryansk—but again, repairs and water trials are still ongoing.

Nor were there any breakthroughs last year with the Burevestnik unlimited-range cruise missile or the Poseidon unmanned underwater vehicle. At the beginning of 2024, Putin said the completion of their testing stages was imminent, but at a meeting of the Defense Ministry board at the end of the year, neither he nor the defense minister made any mention of them.

In addition, coastal infrastructure facilities at the home station of the Belgorod and Khabarovsk special-purpose nuclear submarines, which are to carry Poseidon super-torpedoes in the Pacific Fleet, are still not ready. The Belgorod’s official entrance into service has been delayed, though it is already undergoing trial operations in the Northern Fleet, while the Khabarovsk has been expected to be launched for at least five years.

According to the Defense Ministry, Russia’s strategic nuclear forces are 95 percent updated—just as in the year before. Previously, they were being modernized 25 percent faster than the Russian military as a whole. But now, amid wartime conditions, the defense industry’s priorities have shifted toward conventional forces, while sanctions and additional civilian burdens placed on military factories have also contributed to a drastic slowdown in the creation of strategic weapons.

Another development of 2024 was that it became clear once and for all that neither Ukraine nor NATO would be scared by tales of new Russian strategic weapons. In the current confrontation, medium-range missiles are in any case far more useful. So now the attention of the Russian leadership and the resources of the military-industrial complex will be focused on the Oreshnik and Putin’s other pet missile projects, leaving the Russian leader to try to frighten the West with the prospect of growing missile capability in Europe and a new arms race.

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

Unexpectedly, Trump’s America appears to have replaced Putin’s Russia’s as the world’s biggest disruptor.

Alexander Baunov

Baku may allow radical nationalists to publicly discuss “reunification” with Azeri Iranians, but the president and key officials prefer not to comment publicly on the protests in Iran.

Bashir Kitachaev

The Kremlin will only be prepared to negotiate strategic arms limitations if it is confident it can secure significant concessions from the United States. Otherwise, meaningful dialogue is unlikely, and the international system of strategic stability will continue to teeter on the brink of total collapse.

Maxim Starchak

For years, the Russian government has promoted “sovereign” digital services as an alternative to Western ones and introduced more and more online restrictions “for security purposes.” In practice, these homegrown solutions leave people vulnerable to data leaks and fraud.

Maria Kolomychenko

Geological complexity and years of mismanagement mean the Venezuelan oil industry is not the big prize officials in Moscow and Washington appear to believe.

Sergey Vakulenko