Unexpectedly, Trump’s America appears to have replaced Putin’s Russia’s as the world’s biggest disruptor.

Alexander Baunov

{

"authors": [

"Vladislav Gorin"

],

"type": "commentary",

"blog": "Carnegie Politika",

"centerAffiliationAll": "",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center"

],

"collections": [

"Politika: The Best of 2025"

],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center",

"programAffiliation": "",

"programs": [],

"projects": [],

"regions": [

"Russia"

],

"topics": [

"Economy",

"Domestic Politics",

"Political Reform"

]

}

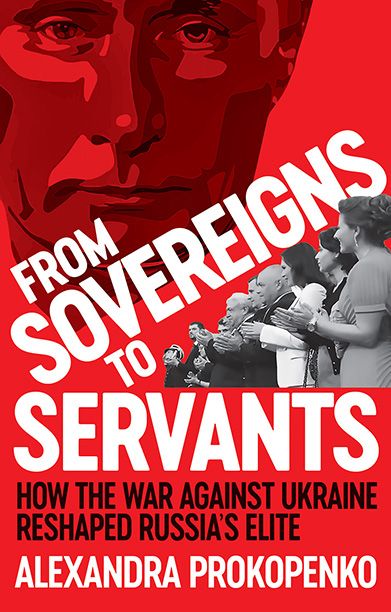

A new book by Alexandra Prokopenko looks at why the Russian ruling class became the regime’s willing servants—and how they might fare in a post-Putin world.

Alexandra Prokopenko’s From Sovereigns to Servants: How the War Against Ukraine Reshaped Russia’s Elite waspublished in Russian on December 1, 2025, and the English edition will bereleased in July 2026. In the book, Prokopenko—a researcher and fellow at the Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center—writes about how Russian bureaucrats and businesspeople (those now often called “technocrats” who would formerly have been referred to as “in-system liberals”) became the servants of Russian President Vladimir Putin, carrying out the orders of an autocrat, even when they disagree with his decisions.

Prokopenko herself might once have been described as a “young technocrat,” having worked for several years as an adviser at Russia’s central bank. However, following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, she quit her job and left the country. Before working for the central bank, Prokopenko spent eight years as a reporter in the Kremlin pool (a group of journalists covering Putin), where she met sources at the highest level of the Russian government and wrote articles about them—until her accreditation was revoked in 2017.

In the process of writing this book, Prokopenko spoke with many of her old acquaintances in the top and middle tiers of the Russian bureaucracy, as well as those working in state-linked companies. She presents the history of Russia’s ruling class over the last twenty-five years as a series of compromises. By making those compromises, bureaucrats and the managers of major companies, she argues, ended up losing the qualities that would allow them to be described as an “elite.”

Prokopenko mostly uses the term “nobiles” for her subjects because, as she puts it, Russia’s ruling class “has stopped being able to generate meaning, develop shared values, or a vision for a desired future—in other words, do what makes an elite an elite.”

It’s worth noting that From Sovereigns to Servants does not deal with Russia’s security services, police, and armed forces, but focuses solely on Russia’s civilian bureaucracy. Despite appearances, this is not a homogenous entity: it includes Putin’s acquaintances from his time working in St. Petersburg (for example, German Gref, the head of state-owned banking giant Sberbank), market reformers who came into government under Putin’s predecessor (like Alexei Ulyukayev, a former economy minister jailed on corruption charges), young functionaries who have forged careers under Putin (like Maxim Oreshkin, Putin’s economic aide), and managers who were recruited into the state sector from corporations in the 2010s.

Many of these people entered public service because they believed that they could be of use to Russian society. They assumed that, even in an autocracy, there would be a role for rational agents. However, the nature of the selection process and the informal practices that are rife in Russian politics meant that the Russian elite, “which should act as a counterweight to the autocrat,” lost its autonomy and became “executors of the president’s will, and flatterers and lackeys.”

Instead of discussing, developing, and making policy, technocrats ended up doing nothing more than overseeing the consequences of decisions taken without their input. Putin needs anti-crisis managers to deal with problems caused both by global phenomena outside Russia’s control (like the financial crisis of 2008 or the coronavirus pandemic), as well as processes and events unleashed by the country’s political leadership (above all, Putin’s war on Ukraine that began back in 2014). Crisis management skills have been particularly in demand since the full-scale invasion in 2022 and the imposition of Western sanctions. The paradox is that most of the Russian establishment thought the war was a disastrous mistake that destroyed much of what they had worked toward in previous years.

From Sovereigns to Servants is written as a journalistic account, and includes colorful descriptions of many top officials. One literally sat on his iPhone out of fear of surveillance (either by Russian or U.S. security services). Others suddenly discovered an interest in long walks in the forest—also out of fear they were being monitored. In conversations, they would say they did not understand why Putin had attacked Ukraine—then they would break off and express concern that their words could lead to them being assassinated.

At the same time, they are also angry at the European Union and the United States (because of the sanctions on Russia’s ruling class, which they believe could not have stopped Putin from going to war), and are proud of how Russia has been able to withstand the Western measures.

Prokopenko suggests that fear is the major factor—in addition to sanctions—that caused the aristocracy to rally around Putin after the start of the war. This is not only the fear of losing one’s career, property, or even life. It is the fear of “social death.” One of Prokopenko’s interlocutors compared being part of Russia’s ruling class to being a member of the mafia; another said officials who lose their jobs suddenly see their telephones go quiet. Either way, being employed provides a sense of being part of an influential group, whose members are united by a shared secret. That secret is knowledge of how the system really operates: informally, illegally, and with procedural violations.

From Sovereigns to Servants argues that Russia’s ruling class is disillusioned and fragmented. For one, the apparent suicide of the dismissed transport minister Roman Starovoit in 2025 was a reminder of the fragility of everyone’s position. For another, the idea that had brought together much of the establishment, “autocratic modernization”—that despite the authoritarian system, a rational state, capable of learning lessons and balancing interests, could still emerge in Russia—has obviously turned out to be a failure.

Toward the end of her book, Prokopenko tackles one of the most interesting political questions in Russia today: What will happen to the servants when their master disappears? Her answer is that the Russian system, which has been built to cater to a specific autocrat, “will come up against a critical lack of autonomy.” She also writes that there will be “a vacuum that may be filled with conflicts—both between different aristocratic groups, and between the aristocracy and society, which has an entirely different set of expectations of the state … Isolation, accumulated frustrations, and non-existent institutional controls could lead to an extended period of instability and a battle for control of a disintegrating system, rather than an orderly transfer of power.”

All this is somewhat reminiscent of the Soviet Union’s experience of the transition from the personalized dictatorship of Joseph Stalin to a more collective form of leadership under Nikita Khrushchev, who was himself replaced a few years later for undermining collective leadership. In other words, the Soviet bureaucracy, which was in a much more subordinate position than its modern equivalent, was able to block someone from the military or security forces from taking power, prevent the emergence of a new dictator, and end repression against the establishment. Officials in a post-Putin world will likely have a similar opportunity to regain some of their lost autonomy. The same cannot be said for Russian society as a whole.

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

Unexpectedly, Trump’s America appears to have replaced Putin’s Russia’s as the world’s biggest disruptor.

Alexander Baunov

The Kremlin will only be prepared to negotiate strategic arms limitations if it is confident it can secure significant concessions from the United States. Otherwise, meaningful dialogue is unlikely, and the international system of strategic stability will continue to teeter on the brink of total collapse.

Maxim Starchak

The story of a has-been politician apparently caught red-handed is intersecting with the larger forces at work in the Ukrainian parliament.

Konstantin Skorkin

For years, the Russian government has promoted “sovereign” digital services as an alternative to Western ones and introduced more and more online restrictions “for security purposes.” In practice, these homegrown solutions leave people vulnerable to data leaks and fraud.

Maria Kolomychenko

Geological complexity and years of mismanagement mean the Venezuelan oil industry is not the big prize officials in Moscow and Washington appear to believe.

Sergey Vakulenko