Nathalie Tocci, Jan Techau

{

"authors": [

"Jan Techau"

],

"type": "commentary",

"blog": "Strategic Europe",

"centerAffiliationAll": "",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"Carnegie Europe"

],

"collections": [],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Europe",

"programAffiliation": "",

"programs": [],

"projects": [],

"regions": [],

"topics": [

"Security"

]

}

Source: Getty

The Responsibility to Inspect

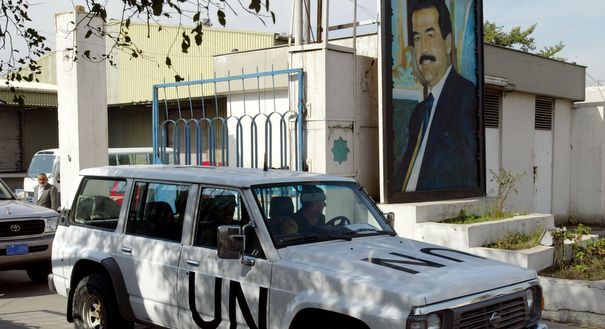

Just as the Responsibility to Protect legitimizes intervention in a sovereign state that fails to guarantee basic security and human rights for its own citizens, the Responsibility to Inspect would allow for such an intervention if a state refuses to have its nuclear ambitions checked.

When it comes to the Iranian nuclear stand-off, most people believe that the scandal at the heart of the matter is Iran's unwillingness to cooperate with the international community and to allow inspections. And they are right. Under the NPT treaty, which Tehran has ratified, the country is obliged to give international monitors access to its nuclear facilities so they can verify that Iran's civilian nuclear projects are not being used to create weapons. Iran rejects inspections and its stubbornness has brought the world to the brink of a severe security crisis.

What's at least as scandalous, however, is the utterly pitiful toothlessness of the sanction regime foreseen by the NPT. Like all international law, it depends primarily on the willingness of those involved to accept the binding nature of the rules they have signed on to. Those who are in violation have little more to fear than maybe some international shaming and, in the worst case, economic sanctions—which rarely achieve their desired effect. Enforcement by means of military action is not only difficult to execute, it’s also extremely costly politically. The mere thought of it leads to public hysteria on a global scale. Violators can hide very comfortably behind that hysteria. But simply letting the violators off the hook is unacceptable, so something else needs to be done. The sanctions regime itself needs to change. It needs to be made significantly more robust. What we need is the “Responsibility to Inspect”.

Nuclear arms are the most powerful and most devastating means of destruction in mankind's arsenal. This makes the NPT more than just your regular, run-of-the-mill international compact, the breach of which could teeth-grindingly be ignored. The treaty regulates the spread of the ultimate weapon, so its importance is far higher than that of most other pieces of international law. This is why it also needs a much more powerful means of enforcement than others.

Just as the Responsibility to Protect (RTP) legitimizes the use of force to intervene in a sovereign nation state that fails to guarantee basic security and human rights for its own citizens, the Responsibility to Inspect (RTI) would allow for such an intervention if a state refuses to have its nuclear ambitions checked and its facilities inspected. RTI would permit such inspections to be conducted by force. The idea is similar, but not identical, to one presented by the Carnegie Endowment before the Iraq War in 2002 under the name of “coercive inspections.” Back then, Carnegie’s president Jessica Mathews wrote:

“A powerful, multinational military force, created by the UN Security Council, would enable UN and International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) inspection teams to carry out "comply or else" inspections. The "or else" is overthrow of the regime. The burden of choosing war is placed squarely on Saddam Hussein.”

RTI, however, would be both more and less ambitious than the proposals of 2002. Less ambitious in that it would not make regime change the “or else” option. Under RTI, regime change or any kind of protracted, large-scale occupation of the inspected country’s territory would have to be explicitly ruled out. RTI would only authorize temporary, geographically limited intrusion into a country for the sake of creating certainty on a subject that does not allow for uncertainty. But on the other hand, RTI would be much more ambitious than “coercive inspections” in that it would aim to gain widespread acceptance as a standard instrument in international law, similar to RTP.

Very clearly, many aspects of RTI still need clarification. How could forceful inspections be conducted militarily? Would the intervening forces only have the right to inspect, or would they also have the right to disable or even destroy the unlawful elements of a nuclear program? Also, like with RTP, there is the dilemma of the slippery slope. What remains of the concept of national sovereignty if certain circumstances warrant its temporary suspension? Will this not lead to the erosion of international law as such, leading us back to a world in which might is right? And there is, of course, the risk of double standards. Wasn't it the West that undermined the NPT by giving India a free ride? Finally, there can be no doubt that, as with RTP, the state in question would most certainly consider inspections under the RTI as an act of war, and answer accordingly. But this would at least make one thing abundantly clear: the party that refuses inspections is the war monger, not the inspector. RTI missions would have to be strictly regulated, but also very robust indeed.

All of these points need careful consideration. But they should not prevent the international community from finally starting to think innovatively about how it can make one of its key instruments designed to avert the ultimate catastrophe more powerful. New standards and instruments in international law require much time and persistent lobbying to gain traction and, eventually, acceptance. They also need precedent, like Kosovo and Libya, which strengthened RTP.

RTI is certainly not without risks. But if gross human rights violations warrant and justify the development of new standards, tools and procedures in international law, such as RTP, then so does the prospect of nuclear armageddon. Maybe even more so. The Iran case, which is driving diplomacy, emotions, and political rationality to the limit, might be the right occasion to try something new. It is time we started thinking about the Responsibility to Inspect.

About the Author

Director, Europe Team, Eurasia Group

Techau is director with Eurasia Group's Europe team, covering Germany and European security from Berlin. Previously, he was director of Carnegie Europe.

- Can Europe Trust the United States Again?Commentary

- Pre-Reformation Europe and the Coming SchismCommentary

Jan Techau

Recent Work

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

More Work from Strategic Europe

- Macron Makes France a Great Middle PowerCommentary

France has stopped clinging to notions of being a great power and is embracing the middle power moment. But Emmanuel Macron has his work cut out if he is to secure his country’s global standing before his term in office ends.

Rym Momtaz

- To Survive, the EU Must SplitCommentary

Leaning into a multispeed Europe that includes the UK is the way Europeans don’t get relegated to suffering what they must, while the mighty United States and China do what they want.

Rym Momtaz

- Europe Faces the Gone-Rogue DoctrineCommentary

The hyper-personalized new version of global sphere-of-influence politics that Donald Trump wants will fail, as it did for Russia. In the meantime, Europe must still deal with a disruptive former ally determined to break the rules.

Thomas de Waal

- Taking the Pulse: What Issue Is Europe Ignoring at Its Peril in 2026?Commentary

2026 has started in crisis, as the actions of unpredictable leaders shape an increasingly volatile global environment. To shift from crisis response to strategic foresight, what under-the-radar issues should the EU prepare for in the coming year?

Thomas de Waal

- France, Turkey, and a Reset in the Black SeaCommentary

A renewal of relations between France and Turkey is vital to strengthen European strategic autonomy. To make this détente a reality, Paris and Ankara should move beyond personal friction and jointly engage with questions of Black Sea security.

Romain Le Quiniou