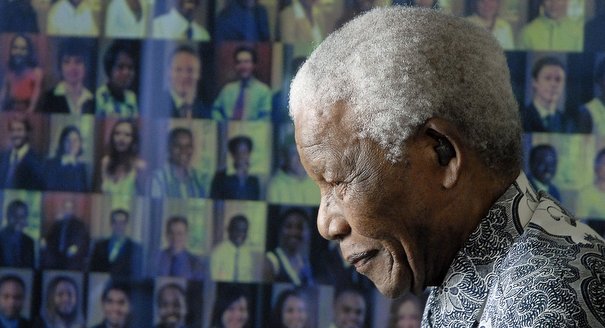

The world is short of heroes. But if there is one person who is indisputably qualified, it is South Africa’s former president, Nelson Mandela.

Mandela, 94, has been in the hospital since December 8. He is being treated for a lung infection, a recurring illness since he contracted tuberculosis in1988 when he was nearing the end of his 27 years in prison.

South Africa’s public keeps asking the military, which is taking care of Mandela, about his health. There is bickering in the government over how much information to release about Mandela’s illness. What an irony considering that it was their patient who made openness one of his many traits!

For most South Africans and many people around the world, Mandela is a hero. He is a beacon for those striving for political decency and freedom. He showed that humanism is not a prerogative of white people.

In any country making the transition to democracy, it is difficult to uphold these values.

It was particularly difficult in South Africa where the black majority had to endure the repressive white minority apartheid regime from 1948 until the early 1990s. Mandela transcended creed, race, ethnicity, and ideology in his bid to make the transition peaceful. It was touch and go. South Africa was often on the verge of widespread violence and recrimination that could have set back democracy for several years.

Coincidentally, South Africa’s transition towards democracy took place at the same time as when Central and Eastern Europe were overcoming decades of communist rule. That part of Europe looked to the European Union to underpin their new democratic freedoms. It had its own heroes like the dissident playwright Vaclav Havel who became president of Czechoslovakia from 1989 to 1992, and then of the Czech Republic from 1993 to 2003.

The European Union, then as now, presents itself as the moral guardian of democracy and its concomitant values. These values originated in the West, but Mandela proved their universality as he led South Africa from apartheid to democracy.

Transitions to democracy are long, difficult, and unpredictable. Just think how long it will take for democracy to take hold across the Middle East. In many of these countries, secular movements and Islamist political parties are struggling to reach an understanding about interpreting, implementing, and protecting universal values.

And don’t forget the uncertainties the future holds for Afghan girls going to school or young women learning new skills. They have been targeted and victimized by Taliban and fundamentalist movements opposed to the opportunities of freedom and democracy. These girls and women will surely become even more vulnerable once the NATO forces leave Afghanistan at the end of 2014 after handing over security to the poorly trained Afghan military and police forces.

Mandela was never naïve about the difficulties in overcoming apartheid.

He believed, at first, in a civic self-defense movement based on non-violence that provided free legal assistance to activists. Eventually, he opted for armed struggle as a last resort. In 1962, as one of the main leaders of the African National Congress, or ANC, he was arrested, charged with sabotage, and sentenced to life imprisonment.

He was released in February 1990 by then president Frederik Willem de Klerk, who had succeeded Pieter Willem Botha. Both white leaders played a major role in realizing, finally, that apartheid was not sustainable as a political, economic, or social policy.

Once released, Mandela led the ANC in the multiparty negotiations that led to the first multiracial elections in 1994.

It must have been tempting for the ANC to seek revenge against the whites. But Mandela chose a path of reconciliation. In 1995, he established the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Witnesses who were victims of human rights violations could give statements and some were chosen for public hearings. Those who perpetrated the violence could testify and request amnesty from civil and criminal prosecution.

Supporters of reconciliation and a peaceful transition praised the TRC. Opponents said they did not go far enough in punishing the perpetrators of apartheid. Mandela stuck to his concept. He knew that revenge has no boundaries.

There are precedents for reconciliation in Europe. The appalling human costs of World War II forced Germany and France towards reconciliation. They ended centuries of bitter and violent enmity that had often plunged the continent into war.

Recently, Poland and Russia have begun a reconciliation of sorts. The countries in the Balkans, scarred by the bloody civil warns of the 1990s, are also embarking on this long process.

But governments in Europe are vulnerable to populism, a trend that is all too common in the EU. Had Mandela, when he was president between 1994 and 1999, resorted to populism, such as playing the anti-white card, South Africa today would be a very different country. The current ANC leaders, however, are dangerously close to reneging on Mandela’s fight for progress, justice, and fairness.

Mandela’s illness, and the international attention given to the reports about his health, may be a timely reminder to the ANC leadership of the values they should be proud to uphold. European governments, given the temptation of short-term populist and racist policies, need that reminder too.