Michael Pettis

{

"authors": [

"Michael Pettis"

],

"type": "commentary",

"blog": "Strategic Europe",

"centerAffiliationAll": "",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"Carnegie Europe"

],

"collections": [],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"programAffiliation": "",

"programs": [],

"projects": [],

"regions": [

"Asia"

],

"topics": [

"Climate Change"

]

}

Source: Getty

China’s Difficult Year 2013

This year may mark the beginning of China’s most difficult period since the beginning of the reforms in 1978.

This year may mark the beginning of China’s most difficult period since the beginning of the reforms in 1978. While Chinese households have benefitted from many years of rapid growth, their share of the economy has declined sharply over the past three decades. What is more, rising income inequality has put China among the most unequal societies in the world.

As a result, ordinary Chinese households receive an extraordinarily small share of what they produce. This is why household consumption, which in most countries accounts for 60 to 70 percent of total demand, is so low in China, accounting for much less than 40 percent of total demand.

In Spain we are used to too much consumption being a problem, but too little consumption can be an even bigger problem. It means that Chinese economic growth depends mainly on increasing investment, but after so many years of the highest investment rate in the world, China can no longer invest productively. It has been wasting investment spending on a massive scale for a long time now.

Wasted investment generates growth in the short term, but it also means that debt rises much more quickly than the ability to repay the debt, and Chinese debt levels are too high already. In order to protect China from the risk of a debt crisis, Beijing must slow the growth in debt, and the only effective way to do this is to reduce investment. Lower investment, of course, will mean slower economic growth in the short term.

This is the challenge Beijing faces. China’s new leaders have made it clear that they want to change China’s growth model, but it won’t be easy. Powerful groups and families have benefitted greatly from the existing growth model. If Beijing reduces investment, these groups and families will see a sharp fall in their power and wealth, and they will oppose it.

This is not a new problem. Many developing countries have experienced periods of rapid growth. But once the economic requirements change, they have a great deal of difficulty adjusting largely because their business and political elites resist the necessary reforms.

For example many Latin American countries, most famously Brazil, experienced “miraculous” economic growth in the 1960s and 1970s. By the mid-1970s, these countries had developed tremendous imbalances within their economies. Debt, like in China, was rising too quickly.

It turned out to be very difficult for these countries to reform their economies. The groups that had benefitted from massive spending by the government did not want that spending to end. Because they had become very powerful, they were able to prevent reform, and as a result Brazil and other Latin American countries continued to invest too much and grow quickly into the late 1970s even as the economies of the United States and Europe went into recession.

Because that growth was powered by rising debt, it could not continue. In 1980-81 growth slowed sharply as governments found it increasingly difficult to borrow at home or abroad. Once growth slowed, the debt became such a huge problem that in the 1980s Latin America suffered a debt crisis, with a “lost decade” of negative growth, high unemployment, and political upheaval.

This is not to say that China necessarily faces the same prospects, but it is important to remember that nearly every country in history that has enjoyed many years of miraculous growth driven by high levels of investment later suffered either from a debt crisis or a lost decade of growth. China must urgently transform its economy if it is to avoid the same fate.

The new leadership in Beijing increasingly realizes what it must do. It must cut back investment and give households a greater share of what they produce by raising wages sharply and by paying much higher interest rates to households who leave their savings in bank deposits.

But these reforms will cause wealth to shift from state-owned enterprises and local governments to households and small businesses, and this is likely to be very unpopular in some powerful quarters. For the past two years, wealthy Chinese have been taking money out of the country at an accelerating pace as worries about political and financial uncertainty rise.

Overcoming this opposition is Beijing’s great challenge. The government must cut investment sharply no matter how powerful the interests that it will run up against are. If it is able to do so over the next few years, Chinese growth will slow considerably, but its economy will become healthier and more sustainable.

If Beijing fails, growth rates might stay high for one or two more years as money continues to pour into investments that produce little economic value. But debt will continue rising at an unsustainable pace, and Beijing will eventually be forced to pay the price. The stakes are high and the outcome is uncertain. 2013 will be a very important year for China.

About the Author

Nonresident Senior Fellow, Carnegie China

Michael Pettis is a nonresident senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. An expert on China’s economy, Pettis is professor of finance at Peking University’s Guanghua School of Management, where he specializes in Chinese financial markets.

- What’s New about Involution?Commentary

- Using China’s Central Government Balance Sheet to “Clean up” Local Government Debt Is a Bad IdeaCommentary

Michael Pettis

Recent Work

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

More Work from Strategic Europe

- Taking the Pulse: Has Europe Given Up its Leadership on Climate Change?Commentary

COP30 takes place amidst increased pessimism about the world’s commitment to energy transition and ecological protection. Beset by a host of other challenges, can Europe still maintain its role as a driver of global climate action?

Thomas de Waal

- The EU’s 2040 Target Is About Much More Than Just ClimateCommentary

The EU’s ambition to slash carbon emissions by 90 percent by 2040 is challenged by internal divisions and global turmoil. But this target must cement a new era of European climate action, linked to innovation, competitiveness, and security.

Emil Sondaj Hansen

- Europe’s Playbook for Climate Engagement with the United StatesCommentary

Europe should leverage the U.S. climate policy shift and safeguard its green transition goals by building cooperation on geothermal energy among other things and focusing on technologies that enhance security and decarbonization.

Milo McBride

- Rethinking the EU’s Strategic Partnerships in Times of CrisisCommentary

Geopolitical shifts have put into question the effectiveness of the EU’s strategic partnerships. Crises in its vicinity present the union with an opportunity to reassess this foreign policy framework.

Meltem Müftüler-Baç, Ezgi Uzun-Teker

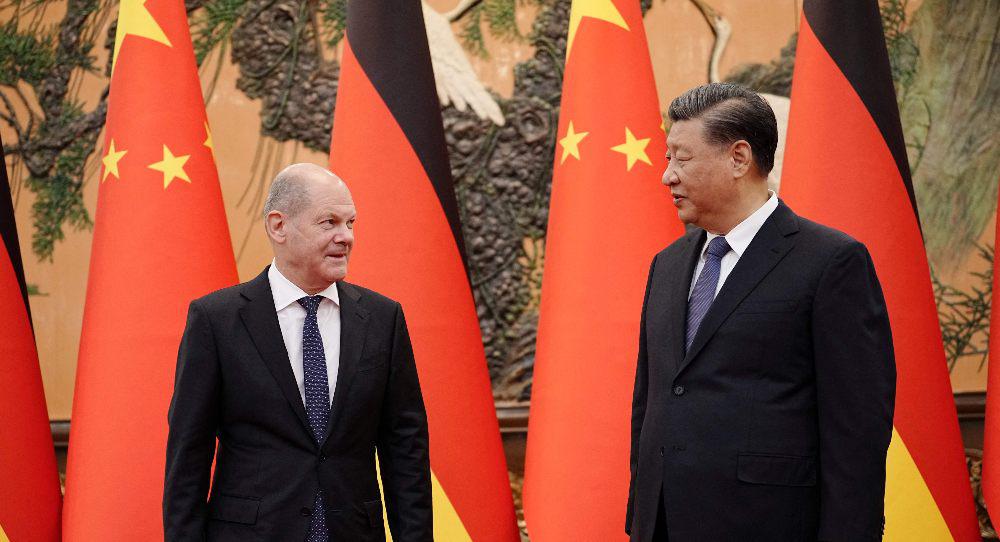

- Scholz’s Visit to China Confirms Germany’s Political WeaknessCommentary

Germany could shape the outcomes of the wars in Ukraine and Gaza. Its reluctance to do so reveals a leadership unwilling to match its economic strength with political influence.

Judy Dempsey