The hyper-personalized new version of global sphere-of-influence politics that Donald Trump wants will fail, as it did for Russia. In the meantime, Europe must still deal with a disruptive former ally determined to break the rules.

Thomas de Waal

{

"authors": [

"Judy Dempsey"

],

"type": "commentary",

"blog": "Strategic Europe",

"centerAffiliationAll": "",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"Carnegie Europe"

],

"collections": [],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Europe",

"programAffiliation": "",

"programs": [],

"projects": [],

"regions": [

"Middle East",

"North America"

],

"topics": [

"Security"

]

}

President Obama wants the issue off his desk, and Iranians say they have no red lines. So can talks begin soon?

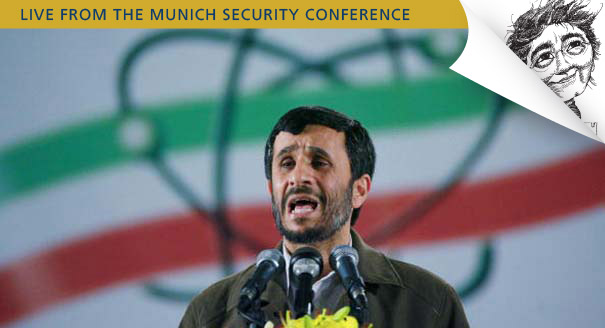

U.S. Vice President Joseph Biden threw down the gauntlet to the Iranian government. At the Munich Security Conference (MSC), Biden said the administration was willing to begin bilateral talks with Tehran, with no conditions.

Diplomats here said Biden’s offer shows that President Obama wants the issue off his desk.

So when Ali Akbar Salehi, Iran’s foreign minister, took to the podium on Sunday morning, there was huge interest. The audience really wanted to know what Iran thought of the U.S. offer.

Salehi is one of the country’s most experienced diplomats.

Indeed, European and Middle Eastern diplomats attending the MSC told Carnegie Europe that he represents the more reasonable face of Iran’s diplomatic service.

When asked about whether Iran would take up Washington’s offer, Salehi replied: “We have no red lines.” Then he added: “We want these negotiations to take place on the basis of equality. We want the negotiations to be comprehensive.”

So is this the breakthrough the international community has been waiting for? Unfortunately, it probably isn’t. The way Iran sees the world is just too different from any Western perspective. That’s what Salehi’s speech in Munich showed.

The United States has many unsolved issues with Iran ever since it broke off diplomatic relations over thirty years ago after the fall of the Shah and the occupation of the U.S. embassy in Tehran. But clearly, the nuclear question is particularly important.

For several years, the five permanent members of the UN Security Council, the United States, Britain, France, Russia, and China, plus Germany, have been negotiating with Iran over its nuclear program.

The United States and Europe are convinced that Iran is developing its nuclear program for military use and not just for peaceful purposes. They, along with the UN nuclear energy watch dog, the International Atomic Energy Agency, have been trying to persuade Iran through a policy of containment and deterrence—meaning sanctions—to come clean about its program.

When Salehi was asked about the goals of Iran’s nuclear program, he launched into a long account of Iran’s rich history, its long civilization, and its outstanding scientific tradition. And then he said Iran would not be dictated to by any power. “We will be nobody’s lackey,” he insisted.

During this 115-minute panel discussion, besides shirking the answer about his country’s nuclear ambitions, Salehi blamed the international community for singling out Iran and not curbing the nuclear programs of other countries. He didn’t mention the case of Israel, but he certainly implied it. The international community, he said, was not interested in truth.

Ruprecht Polenz, an experienced foreign affairs specialist in Germany’s governing Christian Democratic Union party, was not prepared to remain silent over Salehi’s digressions.

In a rare show of outspokenness, he said that if Salehi cared so much about his country’s rich tradition, he should be worried about how the sanctions imposed by Europe and the United States were damaging his own people and even the fabric of society.

Moreover, added Polenz, if Salehi had nothing to hide about Iran’s nuclear program, why didn’t he spell out what Iran wanted to do with its nuclear power?

“Here in Germany, we have accidents on the motorway. One driver goes in the opposite direction of the traffic flow. When he is questioned, he blames the other drivers. It is they who were driving in the wrong direction,” Polenz said. “Iran is like a ghost driver. Always blaming others.”

Polenz, too, criticized Iran’s human rights record and how it was supporting the Assad regime in Syria.

When participants asked Salehi why Iran was supporting Assad by supplying it with weapons and fighters, Salehi simply replied: “The truth will decide.”

Saheli’s replies were both frustrating and fascinating. They show an immense difference in outlook, which was important to hear.

“There was a bit of posturing,” said a European diplomat involved in the Iran talks. “But frankly, you got an insight into how Iran believes the rest of the world is... This attitude makes negotiations very, very difficult.”

The panelists did not dare believe that 2013 would be the year for a breakthrough.

“One thing is sure: there will be no breakthrough this year. The current negotiations can drag on,” said panelist Professor Vali Nasr, dean of the Paul Nitze School of Advanced International Studies. “But I think it has to be accepted that the policy of containment and sanctions have not worked. A new approach is needed,” he added.

The Obama administration has no illusions about Iran’s negotiating style. It is common knowledge here that Washington and Iran have established back channels. Perhaps there, the language and style is very different. Certainly, one would hope so.

Biden, naturally, did not reveal what the United States would put on the table. But if the administration wants this issue off the president’s desk, Washington has no option but to offer some irresistible trade-off.

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

The hyper-personalized new version of global sphere-of-influence politics that Donald Trump wants will fail, as it did for Russia. In the meantime, Europe must still deal with a disruptive former ally determined to break the rules.

Thomas de Waal

2026 has started in crisis, as the actions of unpredictable leaders shape an increasingly volatile global environment. To shift from crisis response to strategic foresight, what under-the-radar issues should the EU prepare for in the coming year?

Thomas de Waal

A renewal of relations between France and Turkey is vital to strengthen European strategic autonomy. To make this détente a reality, Paris and Ankara should move beyond personal friction and jointly engage with questions of Black Sea security.

Romain Le Quiniou

Europe is designing a new model of collective security that no longer relies on the United States. For this effort to succeed, solidarity between member states that have different threat perceptions is vital.

Erik Jones

Beset by an increasingly hostile United States, internal divisions, and the threat of Russian aggression, the EU finds itself in a make-or-break moment. U.S. President Donald Trump calls it a decaying group of nations headed by weak leaders. Is Europe able to prove him wrong?

Thomas de Waal