Judy Dempsey

{

"authors": [

"Judy Dempsey"

],

"type": "commentary",

"blog": "Strategic Europe",

"centerAffiliationAll": "",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"Carnegie Europe"

],

"collections": [],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Europe",

"programAffiliation": "",

"programs": [],

"projects": [],

"regions": [

"Europe"

],

"topics": [

"EU"

]

}

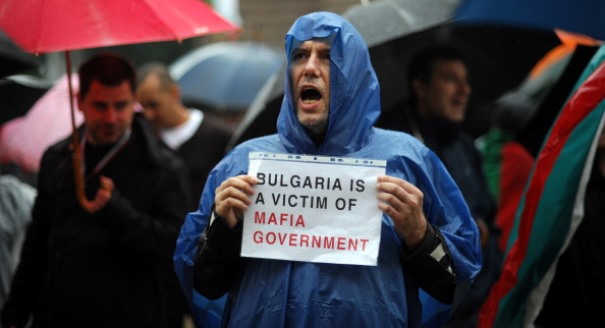

Source: Getty

Is This Bulgaria’s Moment?

Bulgarians have been taking to the streets to protest against systemic corruption. Their big challenge now is how to channel their grievances into a clear political program.

For over forty days, Bulgarians have been taking to the streets of Sofia and other cities across Bulgaria. Tens of thousands are turning out to protest against the corruption that is so pervasive in this small country. Perhaps the protests will mark a turning point that will lead to real political change.

This past Tuesday, demonstrators even blocked the parliament, preventing over a hundred lawmakers from leaving the building. The standoff ended when riot police broke up the demonstrations. That has not, however, stopped further protests.

There have been demonstrations in the past in Bulgaria but nothing on this scale, neither before nor since the country joined the EU in 2007.

It seems that, finally, Bulgarian society has had enough of the country’s corruption, lack of transparency, and contract killings. Recent opinion polls show that two-thirds of Bulgaria’s 7.3 million people support the demonstrators.

The protesters will not easily be fobbed off with promises of cleaner government by their leaders. Too many such promises have been made—and broken—since November 1989, when Bulgarians peacefully toppled Todor Zhivkov’s Communist regime. But they failed to make a clean break with the past.

Perhaps now Bulgaria’s moment has finally arrived. Maybe this is the time when a younger generation, untainted by the dirty politics of the country’s long transition, can take over.

That would be long overdue.

During the 1990s, Bulgaria was one of the neglected outposts of the Balkans. As war raged in the former Yugoslavia, Bulgaria suffered on two counts. First, that conflict as well as Western sanctions against Serbia crippled Bulgaria’s economy. Second, the war gave the country’s former Communist security services and Russian oligarchs an ideal opportunity to gain control of large parts of the economy, including energy.

As experience has shown across most of Eastern Europe since the 1990s, whoever holds the main levers of the economy holds the levers of power as well.

Nowhere has this relationship been as umbilical as in Bulgaria. Regardless of all the preparations during the 2000s for joining the EU, most of the country’s governing politicians only paid lip service to reforms, especially on the judiciary and rules of procurement. Nor did successive governments do much to try and dismantle the mafias.

The EU knew exactly how corrupt Bulgaria was when it became a member. But there was some hope—or wishful thinking—in Brussels that once the country joined, reforms would be speeded up.

Well, that didn’t happen. The European Commission’s monitoring reports on Bulgaria make for depressing reading. Brussels even held back some of the funds destined for Bulgaria to force the country to address its systemic corruption.

But while every government pledged to reform the judiciary, little was achieved. The oligarchs had become a state within a state, causing even sincere efforts to introduce reforms to fail.

Both oligarchs and politicians may now have overplayed their hand.

In May, the Socialist government appointed Delyan Peevski as head of the national security agency. The media mogul, who had served as a minister under a previous Socialist government, already had a reputation for corruption. That clearly did not matter to the politicians who appointed him.

But it did to Bulgaria’s newly self-confident civil society. Days after Peevski’s appointment as security chief, thousands of people, old and young, took to the streets protesting against his new role. Prime Minister Plamen Oresharski quickly gave in and reversed Peevski’s appointment, hoping the matter would end there. But he miscalculated.

For ordinary Bulgarians, Peevski’s removal is just the start. They want something much more fundamental. “Civil society in Bulgaria is voicing strong demands for genuine reform of the ailing state institutions and for effective democracy. These demands are homegrown and have a grassroots pedigree,” argues Ivan Krastev, director of the Center for Liberal Strategies in Sofia.

This homegrown aspect is crucial. There are many interest groups in Bulgaria hoping to discredit the demonstrators, either through provoking violence or by blaming the protests on external agents such as the EU.

The reality is that the EU as a whole is giving Bulgaria’s new civic movement far less support than they could have wished for.

The demonstrators certainly don’t get much help from the European Parliament. The reason is that the two biggest groups there, the Socialists and Democrats and the European People’s Party, have affiliates in Bulgaria’s political establishment. One includes Bulgaria’s Socialist Party among its members, the other the center-right Citizens for European Development of Bulgaria, the country’s former governing party.

The European Commission, at least, has given the protesters some moral support. In a live question-and-answer session with Bulgarians this week, Viviane Reding, the EU’s justice commissioner, said her sympathy “was with Bulgarians protesting against corruption.”

Clearly, it is up to the protesters themselves to take the next step. Their big challenge is how to channel their grievances into a clear political program. For that, they need honest and competent leaders and fully transparent sources of financial support.

Given the enormous popular disgust with the old system, change may finally be possible. Perhaps this really is Bulgaria’s moment.

About the Author

Nonresident Senior Fellow, Carnegie Europe

Dempsey is a nonresident senior fellow at Carnegie Europe

- Europe Needs to Hear What America is SayingCommentary

- Babiš’s Victory in Czechia Is Not a Turning Point for European PopulistsCommentary

Judy Dempsey

Recent Work

More Work from Strategic Europe

- Global Instability Makes Europe More Attractive, Not LessCommentary

Europe isn’t as weak in the new geopolitics of power as many would believe. But to leverage its assets and claim a sphere of influence, Brussels must stop undercutting itself.

Dimitar Bechev

- Europe on Iran: Gone with the WindCommentary

Europe’s reaction to the war in Iran has been disunited and meek, a far cry from its previously leading role in diplomacy with Tehran. To avoid being condemned to the sidelines while escalation continues, Brussels needs to stand up for international law.

Pierre Vimont

- Taking the Pulse: Can European Defense Survive the Death of FCAS?Commentary

France and Germany’s failure to agree on the Future Combat Air System (FCAS) raises questions about European defense. Amid industrial rivalries and competing strategic cultures, what does the future of European military industrial projects look like?

Rym Momtaz, ed.

- Macron Makes France a Great Middle PowerCommentary

France has stopped clinging to notions of being a great power and is embracing the middle power moment. But Emmanuel Macron has his work cut out if he is to secure his country’s global standing before his term in office ends.

Rym Momtaz

- How Europe Can Survive the AI Labor TransitionCommentary

Integrating AI into the workplace will increase job insecurity, fundamentally reshaping labor markets. To anticipate and manage this transition, the EU must build public trust, provide training infrastructures, and establish social protections.

Amanda Coakley