Nathalie Tocci, Jan Techau

{

"authors": [

"Jan Techau"

],

"type": "commentary",

"blog": "Strategic Europe",

"centerAffiliationAll": "",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"Carnegie Europe"

],

"collections": [

"EU Integration and Enlargement"

],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Europe",

"programAffiliation": "",

"programs": [],

"projects": [],

"regions": [

"Europe",

"Eastern Europe",

"Russia",

"North America"

],

"topics": [

"EU"

]

}

Source: Getty

Why the Eastern Partnership Is Crucial for the EU and the West

The EU’s approach toward its Eastern neighbors matters hugely for the region, for the EU, and for the West as a whole. That approach needs to be bolder and more strategic.

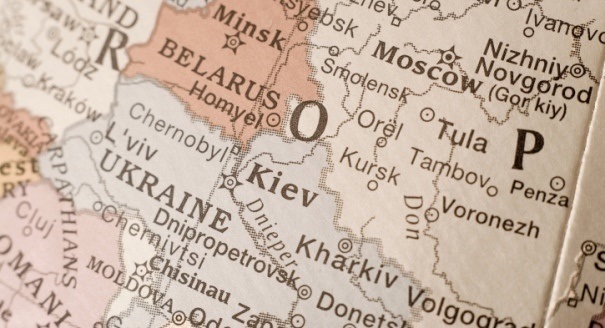

While the world is busy trying not to go completely crazy over Syria and Egypt, the EU is quietly having a stab at the wonderful game of geopolitics. That game is taking place in a completely different theater: Eastern Europe.

Western politicians everywhere should take a close look at how this plays out. Not only are there eminently important issues at stake in countries such as Ukraine, Georgia, Moldova, and Azerbaijan. The EU’s Eastern Partnership could also be the blueprint for Western diplomacy in the emerging “nonpolar” world, a disorderly place with a high demand for stability but without a benevolent hegemon that is dominant and good-natured enough to guarantee it.

The EU’s Eastern Partnership, launched in 2009, is the bloc’s tool for relations with six former Soviet countries: Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine. The EU’s aim is to move these states toward democracy, the rule of law, and open-market economics, in order to stabilize Europe’s Eastern glacis.

This has proven remarkably difficult, as the EU’s most powerful instrument for nudging stubborn neighbors in that direction—EU membership—is not applicable here. Full accession is just not an option for any of the six anytime soon.

So the Eastern Partnership is not only a test case for how powerful the EU can be beyond enlargement. It can also be seen as an example of the difficulties that a weakened West, led by the United States, will face in defending a rules-based liberal world order.

The EU’s attractiveness in its Eastern neighborhood is diminished by years of political and economic turmoil in the EU itself. The bloc is no longer the universally accepted model—emulated energetically by the transforming societies of Europe’s East—that it once was.

The EU lacks the hard power and, more importantly, the political will to play the game on its Eastern flank as a geopolitical contest with Russia. Yet Russia’s newly assertive power keeps dragging it into precisely that kind of game.

Likewise, the Europeans lack the political forcefulness to implement what the EU calls conditionality: to reward those who stay on the path of virtue, and punish those who deviate from it. Many leaders in Brussels and the member states abhor the idea of being accused of paternalism or, worse, neocolonialism.

As a consequence, the EU is engaged in a frantic search for the right tool that gets the right results: forceful yet sensitive, ambitious yet not imposing, target-oriented yet patient. In the meantime, Russia, which clearly looks at the politics of Eastern Europe as a battle over spheres of influence, perceives this agonizing as weakness.

The EU needs to find the solution soon, because after many years of diplomatic activity it is now crunch time. States in Europe’s East are ready to sign association agreements and free-trade deals. The EU’s partner countries expect to hear how the EU intends to move forward with the Eastern Partnership after the first four years. And the EU’s Central European member states, who have the strongest interest in making the initiative a success, want to know how much buy-in they can expect from their Western European partners.

This is the same dilemma that the United States and its allies face, on a larger scale, around the world. The age of Western dominance is over, yet the West still has considerable influence. But it is unclear how the West should use its remaining power smartly, effectively, and in a way that crisis-stricken, war-weary domestic audiences will accept. And it is unclear how to win over equally reluctant audiences abroad for a Western-style liberal world order.

In Eastern Europe, political elites fear getting too close to either Russia or the EU. Becoming too Western and embracing democratic reform could ruin the political business model that keeps them in power. Too much rule of law and transparency is simply too dangerous.

But getting sucked back into the Russian vortex is a similarly nightmarish prospect for them. The states of Europe’s East would become mere puppets of the Kremlin, dependent on the whims of a regime that does not suffer resistance lightly.

Ukraine is the best example of this. Belarus is already much closer to Moscow, yet in principle, the same mechanism applies. Georgia and Moldova are definitely willing to go West, but heavy dependencies on Russian energy, unresolved territorial disputes, and divisive domestic politics weigh them down.

How can the EU get out of this dilemma?

There is no simple answer. But just as U.S. President Barack Obama is currently learning the hard way that he needs to deal more robustly with Syria if he does not want to undermine America’s standing in the world, European leaders will have to embrace toughness in the Eastern Partnership if it is to succeed.

Yes, conditionality needs teeth. Yes, the EU is involved in a geopolitical game it cannot afford to lose. And yes, if EU foreign policy is ever to produce strategic results, then Europe’s East probably offers the best chance of getting them. The next four years of the Eastern Partnership should take a much bolder strategic direction.

About the Author

Director, Europe Team, Eurasia Group

Techau is director with Eurasia Group's Europe team, covering Germany and European security from Berlin. Previously, he was director of Carnegie Europe.

- Can Europe Trust the United States Again?Commentary

- Pre-Reformation Europe and the Coming SchismCommentary

Jan Techau

Recent Work

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

More Work from Strategic Europe

- The EU Needs a Third Way in IranCommentary

European reactions to the war in Iran have lost sight of wider political dynamics. The EU must position itself for the next phase of the crisis without giving up on its principles.

Richard Youngs

- Global Instability Makes Europe More Attractive, Not LessCommentary

Europe isn’t as weak in the new geopolitics of power as many would believe. But to leverage its assets and claim a sphere of influence, Brussels must stop undercutting itself.

Dimitar Bechev

- Europe on Iran: Gone with the WindCommentary

Europe’s reaction to the war in Iran has been disunited and meek, a far cry from its previously leading role in diplomacy with Tehran. To avoid being condemned to the sidelines while escalation continues, Brussels needs to stand up for international law.

Pierre Vimont

- Taking the Pulse: Can European Defense Survive the Death of FCAS?Commentary

France and Germany’s failure to agree on the Future Combat Air System (FCAS) raises questions about European defense. Amid industrial rivalries and competing strategic cultures, what does the future of European military industrial projects look like?

Rym Momtaz, ed.

- Macron Makes France a Great Middle PowerCommentary

France has stopped clinging to notions of being a great power and is embracing the middle power moment. But Emmanuel Macron has his work cut out if he is to secure his country’s global standing before his term in office ends.

Rym Momtaz