When in China, keep two things in mind. First, you can never have too much dim sum. Second, be prepared to talk about respect.

Because respect is what China wants. Or so your Chinese counterparts will tell you. Officials, or those speaking as official proxies, will talk about it anyway. Even those who open up a little more and speak in a private capacity will very likely mention the R-word.

Respect is a key building block in the Chinese national narrative, even more so than in Russia or the Arab world, where the word is in ample supply as well.

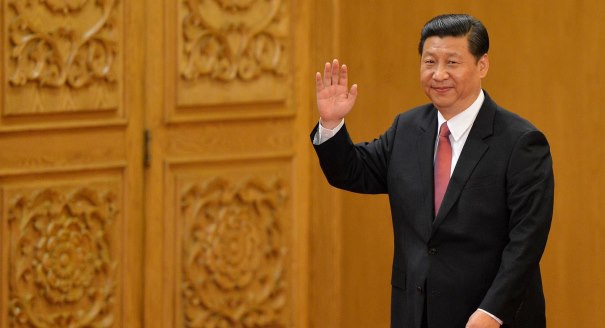

On the surface, the reason for this is clear. Official Chinese historiography has made respect a key concept that forms the core of China’s new identity. Respect features especially prominently in the speeches of Xi Jinping, China’s president, when he talks about Chinese greatness and the “Chinese dream.” After two hundred years of humiliation at the hands of imperialist powers, it is now time for the newly risen China to demand respect—and for others to show it. China is a great nation once more. No need to feel inferior or second rate.

Partly, of course, this is a genuine sentiment. China has strong feelings about the unequal treaties that Western powers forced upon it in the nineteenth century and about Japanese occupation in the 1930s and ’40s. The Chinese are also immensely proud of their economic achievements. They parade their private wealth, which they have achieved in little more than a single generation. And in conversation, they often portray a shocking inferiority complex toward Westerners that has very little to do with facts and everything to do with deep-seated feelings of having lived in a poor, powerless society for so long. The unaddressed traumas of the cultural revolution and of seventy years of dictatorship under the Chinese Communist Party add to the potency of the mix.

But partly, respect is also a political tool. It is based on a carefully nurtured culture of victimhood. It serves the Communist Party as a source of legitimacy vis-à-vis the Chinese people (“You see who has made China great again!”), but it also serves as a tool to frame the debate with foreigners. When respect is invoked, it means that outsiders must accept that it is not their turn, and that China deserves a certain kind of preferential treatment as compensation for past wrongs. Demanding respect is a form of emotional blackmail, designed to create political outcomes.

According to philosophers and anthropologists, Western culture is based on guilt, whereas Chinese culture is based on shame. In the battle over respect, it’s 1:0 for shame. Many Chinese understand very well the widespread feeling of guilt that many Westerners have about their colonial pasts and their earlier political mistakes. They realize that a strategy based on playing the guilt card will often be successful.

The effect can be impressive. Chinese speakers, in the name of respect, will demand the most far-reaching exemptions and exceptions for China on matters such as territorial disputes, trade issues, and human rights. And Westerners, having been given the guilt-inducing respect treatment, will shy away from countering the Chinese arguments. It does not always happen, but it happens often enough to be noteworthy.

Admittedly, it is not always easy to find a good counterargument to respect. Like duty, honor, and pride, respect is almost a nonword in Western culture. These terms have a very reduced meaning in Western political discourse, having been relegated to the realm of the semisacred that is invoked only in Sunday sermons or when honoring fallen soldiers (or in rap music, with its very own culture of victimhood). And so Westerners are often dumbfounded when such hypercharged vocabulary is used as a political tool.

The trick is to remind oneself that respect must be earned, and is not just granted. It comes with the contributions that people and nations make to problem solving.

“The world has a great deal of respect for the remarkable economic progress China has made over the last three decades,” says Paul Haenle, director of the Carnegie-Tsinghua Center in Beijing. “Even greater respect will be given to China as it begins to take on increased responsibility and contribute more meaningfully to the common global good. Demanding more respect as a precondition to engaging more constructively on issues of common concern will not help China gain greater respect, improve its international image, or help the world to resolve crucial global problems.”

A former U.S. diplomat who served in China for many years puts it more bluntly: “I do not pay much attention to Chinese talk about respect. I say to them that I understand, but let’s talk about the business at hand. They are genetically pragmatic, and if they see there is no psychological weakness they can exploit, they will move on.”

The bottom line is that the Chinese can only use the emotional blackmail of respect as long as their counterparts let them. No one intends to treat the Chinese disrespectfully. That is a matter of personal courtesy and correct protocol. But not all of China’s respect narrative needs to be bought. All it takes to see through it is a little confidence. And some self-respect.