In early September 2004, I was sitting in Aleksander Kwaśniewski’s office in downtown Warsaw. He was Poland’s president at the time and he was in a very good mood. Poland had reached its Euro-Atlantic goals, having joined the EU four months earlier and NATO in 1999. Wasn’t that enough for Poland?

No way, said Kwaśniewski. “The very important question is how we see the future of Europe and who our partners will be in the coming years,” he said, referring to Poland’s Eastern neighbors, particularly Ukraine.

“Many countries in Europe have fears about Ukraine,” Kwaśniewski explained. “Some see Ukraine much more on the side of Russian influence than as a part of a European structure. In my opinion, an independent Ukraine, and a country with such a deep sense of self-identity, is good for Europe.”

Almost ten years later, Poland is still trying to complete the unfinished revolution in Eastern Europe. This entails bringing its Eastern neighbors closer to—or into—the EU. That might have seemed an impossible feat a decade ago, when Poland was a mere novice in the EU. But since then, Poland has become much more influential both in the bloc and among its Eastern neighbors, because it has stuck to its strategy.

Nowhere was this clearer than in Poland’s mediating efforts, along with Germany and France, in the Ukraine crisis on February 20–21. Together, the three countries’ foreign ministers, with the backing of EU foreign policy chief Catherine Ashton, stopped the violence—at least for now—and precipitated the ousting of Ukraine’s then president Viktor Yanukovych.

Poland did not achieve such a mediating role overnight. It was part of a long-term goal that the country has pursued for a quarter century. Ever since the collapse of Poland’s Communist regime in 1989, one of Warsaw’s major strategic and foreign policy decisions was to reach out to Ukraine. That was a huge psychological and political decision, given both countries’ past.

During World War II, when Poland was attacked by Nazi Germany and later by the Red Army, both Poland and Ukraine went through terrible ethnic cleansing of their respective minorities. That poisoned Polish-Ukrainian relations until 1989.

But in the early 1990s, Warsaw’s post-Communist government knew that its own security and stability depended on dealing with its past, particularly vis-à-vis Ukraine. Poland did not want a new Iron Curtain to come down on its Eastern borders. Instead, it was hoping for a democratic Ukraine, free of Russian influence.

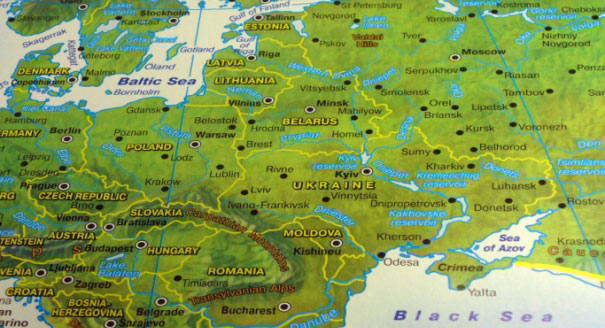

Over the past twenty-five years, Poland has done everything possible to anchor Ukraine into the Euro-Atlantic alliance of the EU and NATO. It has also invested much time and energy in Belarus and Moldova and, further afield, in Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia. And along with Sweden, Poland has cajoled EU governments and the European Commission into revamping their policies toward the new Eastern Europe.

Although the EU’s European Neighborhood Policy does not hold out the perspective of membership, the initiative has given some pro-Western governments, especially in Moldova and Georgia, a strong motivation for introducing reforms. Last November, these two countries initialed association and free-trade accords with the EU at a summit in Vilnius. Meanwhile, Ukraine, Belarus, Armenia, and Azerbaijan turned their backs on the agreements.

Georgia and Moldova are scheduled to sign the accords later this year, provided they can resist pressure from Russia, which has consistently threatened both governments with trade embargoes and other restrictions if they do sign. Poland is well aware of that.

But it is Ukraine that has dominated Poland’s Eastern policy. Since the beginning of its strategy, Warsaw has engaged all the players in this country. During the 2004–2005 Orange Revolution, Kwaśniewski, aware of the potential for widespread violence, flew to Ukraine to mediate a compromise. It was in the same vein that Radek Sikorski, Poland’s foreign minister, flew to Kiev on February 19 to mediate in the recent unrest. Poland did not want to abandon Ukraine and its Eastern policy.

Poland’s achievements in Ukraine are due not only to solid ties with the country itself, however. Warsaw has also made huge efforts to improve its relations with Germany and Russia, both key players in Ukraine’s future. For that, Poland overcame a long history of being a playground for Prussia, Russia, and Nazi Germany.

Successive post-1989 Polish governments have tried to confront this legacy through rapprochement. Donald Tusk’s center-right government, in power since 2007, has gone the furthest. He, and especially Sikorski, embarked on a strategic policy of reaching out to Russia. The aim was to find a common narrative of their past that would allow a predictable and stable relationship.

At the same time, Tusk has forged a close relationship with Angela Merkel, the German chancellor. That has worked wonders for overcoming deep-seated distrust and suspicion.

Poland’s mediating role in Ukraine has been hugely important. That’s not just because Warsaw now has a better relationship with Berlin and Russia than in the past, or because the Ukrainians, by and large, trust the Poles. It’s because Poland wants a safe and democratic Eastern Europe. It wants to complete the revolution.