Every week a selection of leading experts answer a new question from Judy Dempsey on the foreign and security policy challenges shaping Europe’s role in the world.

Ian BondDirector of foreign policy at the Center for European Reform

Neither the West nor the Ukrainians themselves seem prepared. Despite weeks of unrest in the country’s East, only in recent days have senior Ukrainian government representatives visited the region. The EU, NATO, and Ukraine should focus on two things: strengthening Ukraine’s long-term ability to resist Russian pressure; and increasing the short-term cost to Russia of interference in Ukraine.

The top priority should be a successful nationwide presidential election in May, leading to a government with unquestioned legitimacy. That will need plenty of monitors, and extra support in the East to prevent voter intimidation.

Western assistance for Ukraine will not have instant effects, but people need to understand the eventual benefits. The West is still not fighting the information war with Russia, with the honorable exception of Polish Foreign Minister Radosław Sikorski, who spoke recently in Odessa about Poland’s experience of European integration. The EU delegation in Kiev needs constantly to challenge Russian disinformation about EU-Ukraine relations, and do it in Russian.

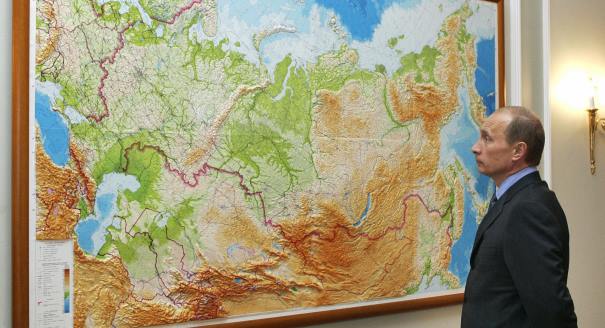

U.S. sanctions have been stronger than EU sanctions so far, but neither have been enough to deter Russian President Vladimir Putin. The United States is hinting at something much tougher; Europeans should do the same. Ukraine is the EU’s backyard too, and the EU should support Ukrainians’ freedom and European choice.

Josef JanningSenior policy fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations

Yes, the West is prepared for Vladimir Putin’s next move. But that is not to say that a Western response will affect decisionmaking in the Kremlin.

Most political leaders in Europe have understood that while Russia’s actions in Crimea lack legal grounds or international political legitimacy, they have created facts that could be reversed only by a massive response—if they can be reversed at all. Western leaders expect Russia to take advantage of political instability in Ukraine to suppress good governance there and possibly break off additional parts of the country in an attempt to rebuild the “Russian world.”

If the latter happens, the West will impose further sanctions, including economic measures, which will hurt businesses in Europe as well as Russia. But such moves are unlikely to influence Putin’s decisions significantly.

At the same time, the West is providing Ukraine with short-term financial assistance to prevent further unrest that could arise if, for example, Ukraine’s Russian gas bills go unpaid. The IMF’s more comprehensive assistance will be conditional on Kiev undertaking reforms, yet that will only alleviate, rather than solve, Ukraine’s social problems.

The time for reform that has been lost since the Orange Revolution of 2004 cannot be made up for. The West can defend its position on the rule of law and the international order, but it cannot save Ukraine.

Karl-Heinz KampAcademic director of the Federal Academy for Security Policy in Berlin

The West had better be prepared, as further disintegration of Ukraine is likely—whether it is spurred primarily by Ukrainian Russians or by Moscow’s active sponsorship. However, being prepared cannot and will not mean the use of military force, even if other parts of Ukraine are annexed. Ukraine is not a NATO member and, like it or not, there is a difference between being in and out of the alliance.

The real issue the West must prepare for is Moscow turning its territorial appetite against a NATO member state. Some in the West claim to know that this is not going to happen—without, alas, disclosing the source of their exclusive knowledge.

Vilnius, Warsaw, and Prague do not share this optimism and are instead urging NATO to prepare for exactly such a scenario. The alliance is likely to make permanent deployments of military forces in Eastern Europe, undertake more military exercises, and increase its contingency planning to send a signal of its resolve and steadfastness.

Washington in particular will do everything to maintain the alliance’s integrity, as rising doubts over the credibility of U.S. security commitments will endanger not only NATO but also America’s broader international influence. During a recent visit to Tokyo, U.S. Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel faced critical questions on what the Ukraine crisis would mean for America’s commitments in Asia. He is sure to have reported this back to his president in Washington.

Roderick ParkesHead of the EU Program at the Polish Institute of International Affairs

Western Europe certainly seems prepared for Russia’s next move, if “prepared” means ready to accept it.

Moscow has played a clever game. First, it undermined Germany’s usual historical justification for engaging in the EU by pointing to historical claims of its own. Now, it is exploiting British Euroskepticism and London’s preference for trade over geography.

It takes the Poles to set the Germans straight. Warsaw can always be relied upon to explain to Berlin the following realities: that if Germany does owe a historical debt to Russia, then it certainly also owes one to Ukraine and Poland; that the West gave Russia no pledge after German reunification about freezing NATO and EU enlargement; and that Moscow’s historical interest in Ukraine does not trump international law.

One can only hope that the Australians set the British straight. During a recent tour of European capitals, Australian Foreign Minister Julie Bishop argued that her country has a keen interest in Ukraine and would be badly exposed if Russia continues to undermine the Western order.

It seems that only countries like Poland and Australia, on the fringes of an increasingly two-tier Western order, really understand what is at stake. Will anyone in Western Europe listen?

Eugene RumerDirector and senior associate in Carnegie’s Russia and Eurasia Program

No, the West is not prepared. The crisis in Ukraine has caught everyone by surprise. The West consistently underestimated Vladimir Putin’s commitment to the goal of consolidating Russia’s influence around its periphery and the capabilities of the Russian military. At the same time, Europe and the United States overestimated Putin’s desire for good relations with the West. European and Americans have yet to come to terms with both misjudgments.

In Ukraine, the twin policies of NATO and EU enlargement—the cornerstone of European security for the past twenty-five years—have come to a screeching halt. Designed to build Europe whole, free, and at peace, the policies were premised on the idea that Russia would not be a threat and would serve as the easternmost pillar of the new European security system. Conflict would be banished from Europe as the zone of stability and prosperity expanded toward—not against—Russia. With Europe free of conflict, NATO would export security to countries and regions beyond Europe.

Some might—and probably will—complain that NATO was expanded under false pretenses. Too late. But the EU and NATO now face their biggest challenge in a generation. Neither can pretend that a policy of “open doors” can proceed as usual. Both organizations have to go back to the drawing board to design a new way forward.

Ulrich SpeckVisiting scholar at Carnegie Europe

The West is not prepared. EU countries and the United States have no strategy to counter Russian pressure in Eastern Ukraine and elsewhere. What the EU does have is the threat of imposing heavy, painful sanctions on Russia. But it is unclear what would trigger such sanctions.

Russia’s tactics are to gain as much control over Eastern Ukraine as possible without getting punished by the EU. By moving slowly on the ground, constantly offering to negotiate, and spreading a pro-Kremlin narrative in the West, Moscow is trying to undermine those in Europe and the United States who argue in favor of tough sanctions. Those tactics seem to be paying off.

On the EU side, there is plenty of self-doubt and fear of confrontation. Russia has confronted the West with a hard choice: sacrifice the sovereignty of post-Soviet countries and international law, or abandon good relations with Russia. It looks very much as if the West is choosing the first option.

That may just delay a clash that is becoming inevitable. Setting no limits on Vladimir Putin will only encourage him to go further. The West may enjoy relief in the short term, but it is setting the scene for a much harsher confrontation in the future.

Stephen SzaboExecutive director of the Transatlantic Academy

Clearly not. For one thing, the West does not know what Vladimir Putin’s next move will be. Will he keep up the pressure on Ukraine and use covert operations to separate the East of the country? Or will he settle for a weak, federalized Ukraine?

Putin has the advantages of strategic proximity, interest, and unity of action, all of which the West lacks. The West will remain divided and reactive, barring a Russian intervention akin to the Soviet Union’s move to crush the Hungarian Revolution of 1956. Putin is unlikely to give NATO or the EU such clear-cut provocation.

The prospects for the West in the short term remain bleak. The United States will not lead, Germany and most of Western Europe will not follow, and the Eastern part of the EU will become increasingly unhinged.