Europe isn’t as weak in the new geopolitics of power as many would believe. But to leverage its assets and claim a sphere of influence, Brussels must stop undercutting itself.

Dimitar Bechev

{

"authors": [

"Misha Glenny"

],

"type": "commentary",

"blog": "Strategic Europe",

"centerAffiliationAll": "",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"Carnegie Europe"

],

"collections": [],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Europe",

"programAffiliation": "",

"programs": [],

"projects": [],

"regions": [

"North America",

"South America"

],

"topics": [

"Economy",

"EU"

]

}

Source: Getty

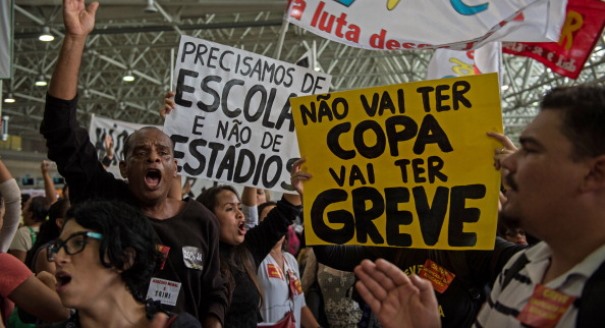

As the 2014 football World Cup gets under way in Brazil, the host nation remains a country dogged by corruption, mismanagement, and underinvestment in public services.

As the São Paulo metro workers suspend their industrial action, pro tem at any rate, auxiliary workers at Rio de Janeiro’s international airport take up the baton and hang out Brazil’s seemingly ubiquitous banner: “EM GREVE”—on strike.

The run-up to the 2014 soccer World Cup has been almost surreal. There has been little sign of the bunting and promotional material that usually accompanies the event. In a recent poll, a whopping 61 percent of the country’s population said that hosting the tournament would be bad for Brazil.

That’s right. The fun-loving, football-mad Brazilians don’t actually want the World Cup. Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff has spent the last week going from one TV show to the next, arguing that the money shelled out for new stadia is an investment in Brazil’s future. Nobody is buying this, except for the consortia who made so much money out of the contracts. Oh, and FIFA, of course.

FIFA, football’s international governing body, selected Brazil as World Cup hosts in 2007, and the International Olympic Committee announced Rio as its choice for the 2016 Games in 2009. The decisions were greeted with exuberance in Brazil and applause around the world. The Land of the Future, as the country was described by the Austrian Jewish writer Stefan Zweig in 1941, was at last about to enter the present.

What were the reasons for this success? Politically, Brazil had enjoyed two immensely successful presidencies. Fernando Henrique Cardoso, who took office in 1995 when Brazil’s new democracy was experiencing appalling difficulties, restored the country’s faith in itself. Not only did he comport himself with dignity, but he slew the great monster of inflation and laid the foundations for a more equitable society.

These foundations were built on by his successor and erstwhile ally turned political enemy, Luiz Inácio “Lula” da Silva. The former trade unionist, who came to prominence in the 1980s as an opponent of Brazil’s military dictatorship, was able to exploit the high value of commodity prices to lift some 40 million people above the poverty line.

Brazil boasted a booming agricultural sector, the promise of huge new oil discoveries, and some indication of a relaxation of regulations governing its highly protected economy. The country looked set to become a member of the BRIC group of nations that was economically successful, socially aware, and resolutely democratic.

This was not just a matter for Brazil. If the country could succeed on these terms, it would give the lie to the growing idea that authoritarian states were better suited to breaking into the global elite. Above all, it would offer an alternative to the Chinese model.

Lula made two big mistakes. First, like so many other heads of state, he failed to put aside funds in anticipation of an economic crisis. When the crisis came, commodity prices crashed, and so too did Brazil’s primary source of income.

Second, during his second term from 2007 to 2011, Lula’s policies shifted away from the national interest and toward the interests of his own organization, the Workers’ Party. This meant focusing on the construction of a whole series of backroom deals between his government, his party, and the political elites of the country’s 27 federal units.

The Brazilian constitution allows an individual to serve two consecutive four-year terms as president. But a person can return for another stint after a break of one term. Lula consciously promoted Rousseff as his successor because she had a weak political base within both the Workers’ Party and the country as a whole. His intention was to return after she had served a single term.

But Lula’s plans were undermined when he developed throat cancer. Although he appears to have beaten the disease, he has not had sufficient time to mount a new campaign ahead of the 2014 presidential election, although he remains the single most influential politician in the country.

Rousseff, as wooden as Lula is elastic, has few reliable allies. She has often found herself at the mercy of regional or sectional interests in the country’s parliament such as the Evangelical and Ruralist blocs.

Faced with the immense task of overseeing the massive program of public works accompanying the World Cup and the Olympics, Rousseff has been found wanting. Gross corruption and mismanagement of infrastructure projects have coincided with ineffective investment in public services—above all health, education, and transportation.

At the same time, concerns about public security are gaining ground. Seven of the most dangerous cities in the world are in Brazil, and even Rio’s flagship pacification program, which aims to drive down violence in the city’s favelas, looks to be coming apart at the seams.

Rousseff knows that things can go badly wrong during this World Cup. That means anything from large-scale strikes and demonstrations to Brazil being knocked out of the competition early. And if something does happen, it could seriously threaten her bid for reelection in October.

The outcome of the World Cup will be the confirmation that Brazil remains a Land of the Future. Unfortunately, Brazilians are not the only losers. Some might view it as a 1-0 victory for autocrats around the world.

Misha Glenny

Journalist and Broadcaster

Misha Glenny is a journalist and broadcaster whose books include The Balkans: Nationalism, War and the Great Powers: 1804-2012, McMafia: A Journey through the Global Criminal Underworld, and DarkMarket: How Hackers Became the New Mafia.

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

Europe isn’t as weak in the new geopolitics of power as many would believe. But to leverage its assets and claim a sphere of influence, Brussels must stop undercutting itself.

Dimitar Bechev

Europe’s reaction to the war in Iran has been disunited and meek, a far cry from its previously leading role in diplomacy with Tehran. To avoid being condemned to the sidelines while escalation continues, Brussels needs to stand up for international law.

Pierre Vimont

France and Germany’s failure to agree on the Future Combat Air System (FCAS) raises questions about European defense. Amid industrial rivalries and competing strategic cultures, what does the future of European military industrial projects look like?

Rym Momtaz, ed.

France has stopped clinging to notions of being a great power and is embracing the middle power moment. But Emmanuel Macron has his work cut out if he is to secure his country’s global standing before his term in office ends.

Rym Momtaz

Integrating AI into the workplace will increase job insecurity, fundamentally reshaping labor markets. To anticipate and manage this transition, the EU must build public trust, provide training infrastructures, and establish social protections.

Amanda Coakley