During his speeches and press conferences on day one of this week’s NATO summit in Wales, Anders Fogh Rasmussen, the alliance’s outgoing secretary general, has been pulling no punches. He has repeatedly said that NATO will protect all its members, especially its Eastern European ones.

Russia’s invasion of eastern Ukraine has certainly galvanized the alliance into agreeing on new measures to protect Poland and the Baltic states. At the same time, another crisis has crept onto NATO’s agenda: the Islamic State, or IS.

The terrible violence that the jihadist group is inflicting on Kurdish communities in northern Iraq, as well as the destruction it is carrying out in Syria, has forced U.S. President Barack Obama to act.

Iraq would have been a discussion item during this week’s NATO summit anyway. But the country has been given a greater profile by the recent beheadings of two U.S. journalists there.

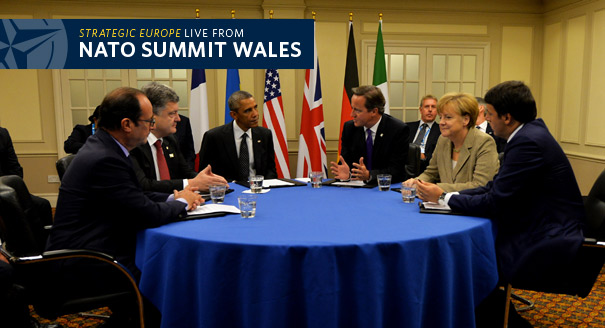

Obama and British Prime Minister David Cameron said on September 4 that these acts would not go unpunished. Cameron added that the UK government would not pay any ransoms to have hostages freed. And Rasmussen insisted that it was the obligation of the international community to stop the jihadists. He specified that this was a task for NATO allies, implying that military action should not be carried out under a NATO umbrella.

This summit shows without any doubt that NATO is facing two big and dangerous threats on Europe’s eastern and southern flanks. Yet for several reasons, the alliance will not take any kind of military action to help Ukraine or to defeat IS.

Why not? In the case of Ukraine, NATO’s reluctance is only partly due to the fact that Ukraine is not even a candidate for alliance membership, let alone a current member. The bigger reason is that the big NATO countries believe that Russia cannot be pushed back. In other words, Kiev cannot win the war in eastern Ukraine militarily.

As for the idea that NATO might arm Ukraine, this notion horrifies many European leaders because of how Russia would react. One alliance diplomat said that Europe would be drawn into a war with Russia were NATO to go down that path.

Instead, the Europeans will impose further sanctions on Russia while trying to pursue a diplomatic path—even though neither approach has deterred Russian President Vladimir Putin so far. In the meantime, Rasmussen has won the support of all NATO allies to strengthen their collective defenses to reassure Poland and the Baltic states. That will not help Ukraine.

A NATO role in stopping the Islamic State’s violence and military gains in Iraq and Syria is not in the cards either. For one thing, it would be impossible to reach consensus among all 28 members on how to deal with the al-Qaeda offshoot. What is more, NATO would not act in the Middle East without a mandate from the UN Security Council.

Rather, given the domestic pressure that Obama and Cameron are facing to take more action against IS, there is a sense that both leaders are seeking some sort of coalition of the willing to confront the group. That would inevitably raise questions about the kind of military role the United States, Britain, and other countries would play in Syria.

With two huge conflicts facing NATO to its south and east, the alliance is slowly moving toward a shared perception of threats. But it is not yet there.

Southern European countries do not feel threatened by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Northern Europeans, in contrast, do perceive the threat from Russia. As for the menace that the Islamic State poses to NATO countries, Western Europeans are largely united in their assessment of the threat, Eastern Europeans less so.

These twin crises show that there is an increasing awareness inside the North Atlantic alliance that if it wants to adopt a long-term strategic outlook, then it needs to agree on the threats its members face. The irony is that even if the allies have come this far, NATO will neither help Ukraine nor confront the Islamic State.

Photo by NATO Summit Wales 2014, used under CC BY-NC-ND / Cropped from original