“I hope you will write something optimistic,” said my interlocutor, the grandson of a Soviet minister and an academic dealing with European issues. But in our hour-long discussion about Russia and Europe, we hadn’t found any common ground on either the history or the present of our mutual relationship. We were just drinking tea in his slightly shabby, hall-like office and agreed to disagree.

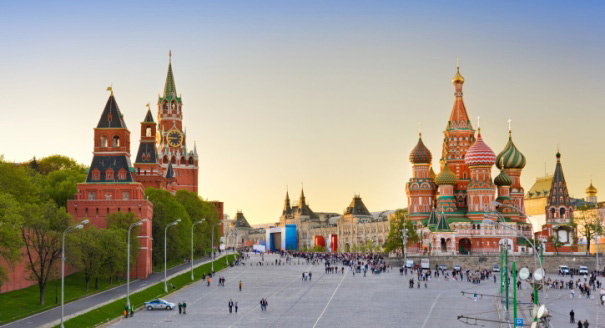

A sense of divorce permeated all my talks during my recent trip to Moscow. Or, to paraphrase German Chancellor Angela Merkel, there was a sense that EU citizens and Russians were increasingly living in two different worlds.

Some people I spoke to gave the situation a more optimistic spin, like the expert on EU affairs who explained to me that Russia had other partnership options in the East. He believed that the BRICS group of Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa would soon become a much more powerful bloc—with a strong positive agenda that would go beyond signaling unease with a Western-dominated global order. His implicit message: Russia didn’t need the EU.

Another well-informed interlocutor saw that view as rather infantile. There was simply no Eastern option to replace ties with Europe, he told me.Other Russians I met felt deeply concerned over the confrontational course that their country’s leadership had taken. They called for both sides, the EU and Russia, to sit together and find a more realistic platform for dialogue. Yes, the past was full of illusions on both sides, a veteran expert of international relations said, but Europeans and Russians still needed each other. But what besides damage control could be on the agenda, I asked. A long, uneasy silence entered the room.

Some of my interviewees were hoping that the current split would turn out to be just a brief episode, as in 2009, when shortly after the previous year’s Russian-Georgian war, the United States announced a “reset” with Russia. The EU, equally, was keen to go back to business as usual with its Eastern neighbor. It is only now starting to dawn in Moscow that this time, things are different.

When would the EU lift its sanctions on Russia, I was asked again and again. Merkel had been always tough on sanctions, I replied, and they wouldn’t be lifted until Russia seriously changed course in Ukraine. At this, the senior editor of a big newspaper smiled and offered me what turned out to be some pretty good mozzarella—made in Russia. But he left no doubt that the sanctions were massively hurting Russia.

The EU and Russia are moving away from each other because they disagree on the meaning of truth.Tweet This

The worlds of the EU and Russia are moving away from each other not just because there is a confrontation over Ukraine but also, and more worryingly, because the two sides disagree on the meaning of truth. A correspondent for a German newspaper explained to me—over a delicious Georgian lunch in a fancy restaurant—that her Russian colleagues often ask her whether she too gets orders from her editors about what to write. They simply cannot believe that Western journalists are driven by the guiding principles of objectivity and truth and not by orders from above.

The narrative in #Russia is increasingly anti-Western, portraying a country under siege.Tweet This

Russians have also lost the sense of truth, other Western journalists told me. I heard how Russians think that everybody lies just as much as each other, and that as Russians they have a simple duty to relate a patriotic narrative. That narrative is increasingly anti-Western, portraying Russia as a country under siege. For half a year or so, it has become increasingly difficult for Western journalists to talk to ordinary people. The atmosphere has become hostile.

The EU and Russia are increasingly at odds with each other. That makes life ever harder for those trapped between the two, in places such as Ukraine and Moldova. And it puts many people in Russia in front of an impossible choice between a liberal Europe and an increasingly anti-Western Russia.