When martial law was declared in Poland in December 1981, Tomasz Kizny, then twenty-three years old, had the choice between emigrating and joining the underground resistance.

Kizny chose the second option. He became a member of the Solidarity trade union movement and spent the rest of the decade taking photos of a dogged resistance that was to bring the Communist party to its knees. In 1989, the regime relinquished its leading role when it joined roundtable talks with the opposition. It was an extraordinary time. Kizny seized the opportunity to capture the past on camera.

“After 1989, I finally had the possibility to get a passport,” Kizny told Carnegie Europe on the eve of the opening of his exhibition, The Great Terror 1937–1938. The photographer’s commemoration of the victims of Stalin’s political repression is now on show at the House of Brandenburg-Prussian History in Potsdam, Germany.

There were two waves of Polish deportations under Stalin. The first was in 1939, the second in 1944–1945. Kizny’s own grandparents and great-grandparents were caught up in the deportations, under which prisoners were sent to the Gulag forced-labor camps. Some never returned.

Until the late 1980s, the Gulags had been taboo in Poland. Kizny had read about them in samizdat, the Soviet-era system of clandestinely printing and distributing censored literature. “It was in the late 1970s when I read [Aleksandr] Solzhenitsyn’s The Gulag Archipelago. It was circulating in samizdat. I had one and a half days to read it and then I had to pass it on. It had a huge impact on me,” he recalled.

After he finished his project about Polish prisoners, Kizny turned his camera to the Gulags themselves. The opportunities to access archives and to travel throughout Russia were opened up.

Under Mikhail Gorbachev, the Soviet Union’s last leader, and Boris Yeltsin, Russia’s first post-Communist president, the past became accessible. The Gulags, the Great Terror of 1937–1938, and the Katyn massacre—a series of mass executions of Poles carried out by the Soviet secret police in 1940—were no longer taboo.

“There was access to the archives,” Kizny recalled. “There was access to the sites where the Gulags once were.” His book, which coincided with Anne Applebaum’s monumental Gulag: A History, was the first visual book about the labor camps.

Kizny then turned his attention to the Great Terror. For him, his often-harrowing work on that subject was about preserving the memory of a horrific episode of Russian history in which 750,000 people from all backgrounds were executed, secretly, between August 1937 and November 1938.

“One in 100 of the Soviet Union’s adult citizens were secretly murdered. That’s 1,600 executions a day,” Kizny said. More than 800,000 were sentenced to up to ten years’ hard labor in the Gulag camps. Only 100,000 survived.

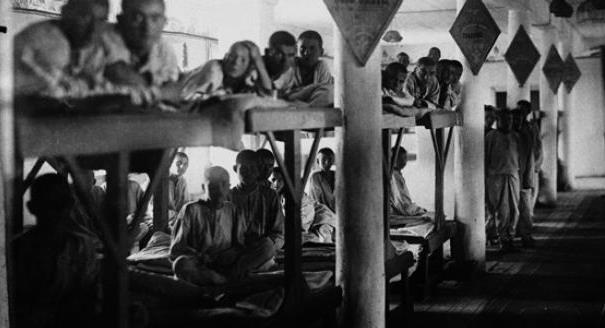

Kizny’s photographs of the Great Terror are special in three ways. The first is the impact of the faces of those prisoners who were photographed by the Soviet secret police when they were arrested. In most cases, the prisoners were murdered within forty-eight hours.

In the exhibition, 79 black-and-white photos of these individuals stare out at you. Most have an expression of bewilderment, fear, and exhaustion. After 1938, the photos were stored in secret archives. “When they came to light in the early 1990s, they became one of the most vivid visual accounts of Soviet Communism’s crimes,” Kizny said.

The second striking aspect of the exhibition is Kizny’s series of pictures of places where there were mass graves. With assistance from Memorial, an independent organization set up in the early 1990s to investigate and preserve the memory of those persecuted in the Soviet Union, Kizny found, visited, and photographed the sites.

His pictures convey a sense of emptiness, of silence, of the shocking reminder that underneath Orthodox churches, forests, factories, and hills are the remains of so many innocent people who were shot and then thrown into mass graves.

The third and most moving aspect of the exhibition is the set of photos and interviews Kizny held with the children of the victims. By now, these are old, sad people. Looking straight into the camera, they recount the past. They talk of the last time they saw their parents, of being unable for years to find out what happened to them, or to discover why, where, and when they were executed—or where they were buried.

“These children were deprived of mourning. Mourning is a part of the human condition. For years and years they knew nothing,” Kizny said. Yeltsin had rehabilitated many of those who died or survived the camps. “Even then,” said Kizny, “when the survivors had been freed from the camps, they were second-class citizens. In many cases, their lives had been broken.”

The interviews, in Russian with German subtitles, have the effect of transporting you back to a distant past dominated by fear, helplessness, and being forgotten. They are very powerful and very moving.

For Kizny and his colleagues and friends in Memorial, investigating, preserving, and talking about the past is tied to a country’s identity—and, indeed, its future. “Memory is so important for the identity of a country. What happens to a nation without a memory, with a selective view of the past?” Kizny asked rhetorically.

Under President Vladimir Putin, Russia’s past is under scrutiny but in completely the opposite way to how Gorbachev and Yeltsin dealt with it. Memorial, for example, has been under constant pressure from the Kremlin, as are many other independent nongovernmental organizations.

In early March 2015, Perm-36, the only museum in Russia created on the site of a former Gulag camp, was forced to close. “It is ceasing its activities and beginning the process of self-liquidation,” according to a statement issued by the museum.

“It’s terrifying what is happening,” Kizny said. “It’s as if there are two kinds of memories competing with each other—the positive and the negative one. The historical policy of the Kremlin is about an identity linked to a great state, not to the tragic things that Russians did to Russians.”

Photo credit: Tomasz Kizny