Deborah Gordon, Smriti Kumble, David Livingston

{

"authors": [

"David Livingston"

],

"type": "commentary",

"blog": "Strategic Europe",

"centerAffiliationAll": "",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"Carnegie Europe"

],

"collections": [],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"programAffiliation": "",

"programs": [],

"projects": [],

"regions": [

"Western Europe",

"France",

"Europe"

],

"topics": [

"Climate Change",

"Foreign Policy",

"EU",

"Economy"

]

}

Source: Getty

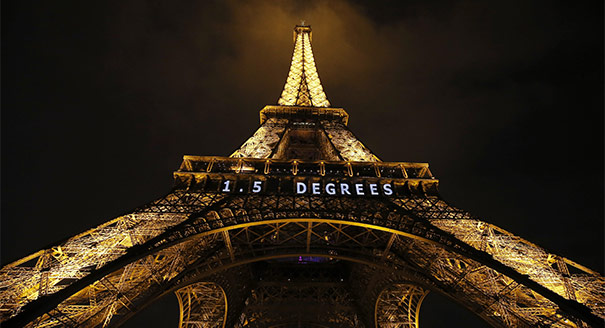

Takeaways From COP21

The looming challenges of translating the historic climate change deal brokered in Paris into meaningful action will dominate the twenty-first century.

Two weeks, numerous drafts, and many secretive huddles later, negotiators at the twenty-first session of the United Nations Conference of the Parties (COP21) in Paris have delivered a unanimous roadmap for tackling climate change in the years ahead. The pact agreed at the climate summit leaves much to be desired, but is nonetheless a substantive and firm starting point.

As one colleague noted before the meeting kicked off, the Paris climate conference was simply “too big to fail.” That prediction ultimately proved correct. Although countries played games of chicken and used various maneuvers to gain the upper hand in negotiations, in the end a compromise agreement was reached. Nearly 200 countries found some semblance of victory in the final deal, which no single actor was willing to block and incur the resulting criticism.

From the outset, it was clear that the Paris summit was going to be a climate potluck, with each country bringing to the table the actions that it felt comfortable committing to. In the end, each major bloc also appears to have received just enough leftovers to make the trip worthwhile.

Small island states and other highly vulnerable countries scored what may have been the largest surprise of the conference, a new aspirational goal to limit global warming to “well below” 2 degrees Celsius from pre-industrial levels, with a limit of 1.5 degrees Celsius the long-term goal with the help of controversial “negative emissions technologies.” The United States was able to keep key aspects of the deal, including emission reduction commitments and some provisions on financing, from having a legally binding status. This was crucial in order to avoid sending the agreement to the U.S. congress, where it would face an almost certain rejection.

Major powers in the developing country bloc were able to maintain numerous references to “common but differentiated” responsibilities, a firewall between developed and developing countries first enshrined in the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC.) The distinction has not matured, despite two decades of economic evolution, such that Greece—an EU member state reeling from austerity measures—was considered a rich country with additional responsibilities, while a wealthy global financial hub like Singapore remained grouped with poorer countries such as Mali, Myanmar, and the Maldives.

In practice, this means that the rhetorical shield used by countries such as China, India, and Saudi Arabia to argue for exemption from ambitious obligations was maintained in the text. At the end of the day, this exemption may not matter much as key provisions, including transparency of regular accounting and reporting, are explicitly intended to be universally applicable.

Crucially, Europe finally lived up to its climate ambitions. Unlike 2009, when the EU was left out of the room while China and the United States negotiated a disappointing last-minute denouement to the Copenhagen climate conference, the EU had a strong role in shepherding the Paris negotiations through to a successful agreement. The union achieved its goal of establishing mandatory five-year reviews of every country’s climate commitments and was very much in the loop for every major development, including the unveiling of a stealth “high ambition coalition” only days away from the summit’s conclusion. This tactical surprise helped to shake up the traditional balance of power and moral authority that has defined countless COPs prior to this one. Aviation and shipping—two sectors under close watch by European regulators—were not addressed in the final text, so this will remain an issue demanding EU engagement in the months and years to come.

On a leadership level, the new climate deal helps to cement the legacy of Angela Merkel as the improbable “climate chancellor” due to Germany’s extensive but under-the-radar climate diplomacy efforts. So, too, will the accord give Brussels new leverage in dealing with Beata Szydło’s climate-skeptic government in Poland. French Foreign Minister Laurent Fabius received widespread praise for a highly transparent but muscular style in presiding over the COP, along with a standing ovation on Saturday after an emotional address thanking all those who had contributed to the process.

Indeed, President Hollande’s government scored a true victory as host, deftly navigating diverse powers toward a multilateral agreement on a matter of long-term strategic importance. This is all the more impressive given the distractions of a “war” against Islamic State, the rise of the National Front, and a sense of fragmentation in the EU and the international system more generally.

France spent significant diplomatic and political capital over the past two years to secure this ambitious outcome at COP21. A number of diplomats told me that France had been far more invested in guiding last year’s COP20 Lima summit than many would suspect, putting the pieces in place to see Paris succeed. With the one-year French presidency of the COP having only officially begun just a week ago, one can expect France to continue to steer discussions ahead of the COP22 in Marrakech in November 2016, with an eye toward avoiding potholes on the road through Paris that might threaten the legacy of this year’s historic summit.

The looming challenges of translating a historic agreement into meaningful action will dominate the twenty-first century. While the commitments submitted by countries ahead of Paris suggest an implied end-of-century warming of 2.7 degrees Celsius, current policies have the world on track for a 3.6 degree Celsius rise. Both of these are nowhere near the 1.5 degree Celsius goal that shook up the climate talks. As the particle board structures at the makeshift COP21 site outside of Paris are dismantled this week, the hard work of building a coherent set of global climate policies awaits.

As sleepless EU Climate Action and Energy Commissioner Miguel Arias Cañete cautioned in the hours following the agreement, “There are many things that we have to deliver in COP22, in Marrakesh and other COPs, but here is the architecture and the design to build a house.”

About the Author

Former Associate Fellow, Energy and Climate Program

Livingston was an associate fellow in Carnegie’s Energy and Climate Program, where his research focuses on emerging markets, technologies, and risks.

- Advancing Public Climate Engineering DisclosureArticle

- Working Around Trump on ClimateCommentary

Erik Brattberg, David Livingston

Recent Work

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

More Work from Strategic Europe

- The EU Needs a Third Way in IranCommentary

European reactions to the war in Iran have lost sight of wider political dynamics. The EU must position itself for the next phase of the crisis without giving up on its principles.

Richard Youngs

- Global Instability Makes Europe More Attractive, Not LessCommentary

Europe isn’t as weak in the new geopolitics of power as many would believe. But to leverage its assets and claim a sphere of influence, Brussels must stop undercutting itself.

Dimitar Bechev

- Europe on Iran: Gone with the WindCommentary

Europe’s reaction to the war in Iran has been disunited and meek, a far cry from its previously leading role in diplomacy with Tehran. To avoid being condemned to the sidelines while escalation continues, Brussels needs to stand up for international law.

Pierre Vimont

- Taking the Pulse: Can European Defense Survive the Death of FCAS?Commentary

France and Germany’s failure to agree on the Future Combat Air System (FCAS) raises questions about European defense. Amid industrial rivalries and competing strategic cultures, what does the future of European military industrial projects look like?

Rym Momtaz, ed.

- Macron Makes France a Great Middle PowerCommentary

France has stopped clinging to notions of being a great power and is embracing the middle power moment. But Emmanuel Macron has his work cut out if he is to secure his country’s global standing before his term in office ends.

Rym Momtaz