European reactions to the war in Iran have lost sight of wider political dynamics. The EU must position itself for the next phase of the crisis without giving up on its principles.

Richard Youngs

{

"authors": [

"John R. Deni"

],

"type": "commentary",

"blog": "Strategic Europe",

"centerAffiliationAll": "",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"Carnegie Europe"

],

"collections": [

"Transatlantic Cooperation"

],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Europe",

"programAffiliation": "",

"programs": [],

"projects": [],

"regions": [

"North America",

"United States",

"Russia"

],

"topics": [

"Security",

"Technology"

]

}

Source: Getty

The incoming U.S. administration risks undermining efforts to deter Moscow from engaging in aggressive forms of interstate competition and hybrid warfare.

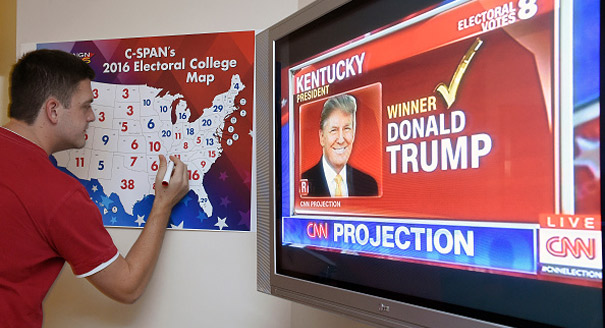

Most of what was in the U.S. intelligence community’s January 6 report on Russian involvement in the 2016 U.S. presidential election came as no surprise to those who have followed this evolving story since last summer. Back then, it seemed clear that Russia had attempted to influence the campaign and ultimately the election, and that a robust American response was necessary—if not before the vote then certainly after.

It may be fair to criticize the administration of U.S. President Barack Obama for not reacting more forcefully in 2016. But the outgoing team also deserves substantial praise for using its remaining weeks both to declassify as much information on Russian interference as possible and to engage in covert and overt responses. Meanwhile, though, the slow, inconsistent reactions of the incoming administration have not simply been confusing: more worrisomely, they risk undermining deterrence by countenancing the Kremlin’s rhetoric of plausible deniability.

During the campaign and immediately after the election, U.S. President-elect Donald Trump would not acknowledge what the intelligence community and private Internet security firms had assessed with high probability for many months: that Russia attempted to influence the race. After he received a classified briefing on the January 6 intelligence report, Trump released a statement that appeared to dilute the role of Russia, lumping it in with “China, other countries, outside groups, and people” attempting to “break through the cyber infrastructure.” More recently, during his January 11 press conference, Trump again watered down Russia’s role, first noting, “as far as hacking [is concerned], I think it was Russia,” but later saying, “it could have been others also.”

It’s not clear why Trump remains reluctant to call out Moscow specifically and explicitly as having conducted an attack against the foundation of American democracy. It is possible that he thinks doing so may in some way delegitimize his election victory or weaken his perceived mandate. If so, these concerns are misplaced, and they pale in comparison with the risk of not singling out Russia and laying blame for this unprecedented attack on U.S. election infrastructure where it belongs—namely, on Russian President Vladimir Putin’s desk.

In fact, failing to fully ascribe malicious cyberattacks during the 2016 election to Russia, and specifically to Putin, is extraordinarily dangerous. If the incoming U.S. administration does nothing to correct this error, it risks fatally undermining any effort at deterring the Kremlin from similar cyberattacks or from engaging in more aggressive forms of interstate competition and hybrid warfare.

Even partly buying into Kremlin rhetoric—while rejecting consensus determinations of the intelligence community—regarding Russian interference in U.S. elections conveys legitimacy on Moscow’s claims of plausible deniability. This equivocation essentially opens the door for Russia to engage in adventurism against Western interests. It is the opposite of deterrence insofar as it signals a willingness to accept Moscow’s version of the truth and hence tolerate Russian misbehavior.

This is an especially dangerous precedent at a time when Russia has evidently decided to fundamentally overturn the European security order by dismembering its neighbors. When the Kremlin shows little hesitation to conduct hybrid operations in and against its European neighbors, anything that undermines deterrence becomes an existential crisis for U.S. allies in northeastern Europe.

To reinforce deterrence in northeastern Europe, safeguard Western security, and correct any misconceptions forming in the minds of Kremlin officials about U.S. responses to future efforts at similar election interference, the incoming administration should take three steps.

First and most importantly, Washington should issue a clear, unambiguous condemnation of Russian interference from the highest level—the president. Given serious concerns over Trump’s position toward Russia as well as widely divergent views toward the country among his senior appointees and nominees, a firm, unequivocal statement from the incoming president is necessary to reinforce deterrence and reestablish redlines. Anybody who claims to have convinced one of the world’s largest automakers to change its overseas investment strategy should understand that words matter.

Second, the new administration should issue a statement of solidarity with other allies—especially those that have elections this year, such as the Netherlands, France, and Germany—that electoral interference will be regarded as an attack on critical infrastructure, an assault on national sovereignty, and hence an unacceptable violation of homeland security. Any violations of that redline should then be met with allied coordination on appropriate covert and overt policy responses in the cybersecurity, diplomatic, military, political, and economic realms. Only by standing together rhetorically and acting in a coordinated fashion can the West effectively and efficiently protect and promote its interests.

Finally, the incoming administration should invite Russia to engage in an exchange of views with NATO member states on acceptable and unacceptable uses of espionage as well as on information operations during election campaigns. Ultimately, this might lead to a set of rules of the road similar to what the United States negotiated with China in 2015. Reportedly, the agreement with Beijing to avoid state-sponsored espionage on private companies for commercial gain has had some positive impact.

Intentionally or not, the incoming U.S. administration’s response to the unprecedented Russian interference in the 2016 presidential election has fundamentally weakened deterrence. How badly it’s been damaged will depend on the speed with which the new president and his team of national security leaders work to clarify American policy and reinforce allied solidarity on this critical question of national sovereignty.

John R. Deni is a research professor of security studies at the Strategic Studies Institute of the U.S. Army War College and an adjunct professor at the American University’s School of International Service. The views expressed here are his alone.

John R. Deni

Atlantic Council

John R. Deni is a research professor at the U.S. Army War College’s Strategic Studies Institute, a nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council, and an associate fellow at the NATO Defense College. He is the author of NATO and Article 5. The views expressed are his own.

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

European reactions to the war in Iran have lost sight of wider political dynamics. The EU must position itself for the next phase of the crisis without giving up on its principles.

Richard Youngs

Europe’s reaction to the war in Iran has been disunited and meek, a far cry from its previously leading role in diplomacy with Tehran. To avoid being condemned to the sidelines while escalation continues, Brussels needs to stand up for international law.

Pierre Vimont

France has stopped clinging to notions of being a great power and is embracing the middle power moment. But Emmanuel Macron has his work cut out if he is to secure his country’s global standing before his term in office ends.

Rym Momtaz

Integrating AI into the workplace will increase job insecurity, fundamentally reshaping labor markets. To anticipate and manage this transition, the EU must build public trust, provide training infrastructures, and establish social protections.

Amanda Coakley

EU member states clash over how to boost the union’s competitiveness: Some want to favor European industries in public procurement, while others worry this could deter foreign investment. So, can the EU simultaneously attract global capital and reduce dependencies?

Rym Momtaz, ed.