The Dutch parliamentary election on March 15 is the first in a series of key European votes in 2017 and has the potential to influence National Front Leader Marine Le Pen’s chances of becoming French president in May. Yet election debates in the Netherlands appear to be taking place in splendid isolation.

Refugee flows, the integration of immigrants, and the future of the EU are all on the table, but political parties are paying more attention to domestic concerns such as the retirement age, the costs of healthcare insurance, labor-market reform, euthanasia, and charges for driving during rush hour. This range of topics points to the high degree of fragmentation in a campaign that still seems not to have taken off in earnest.

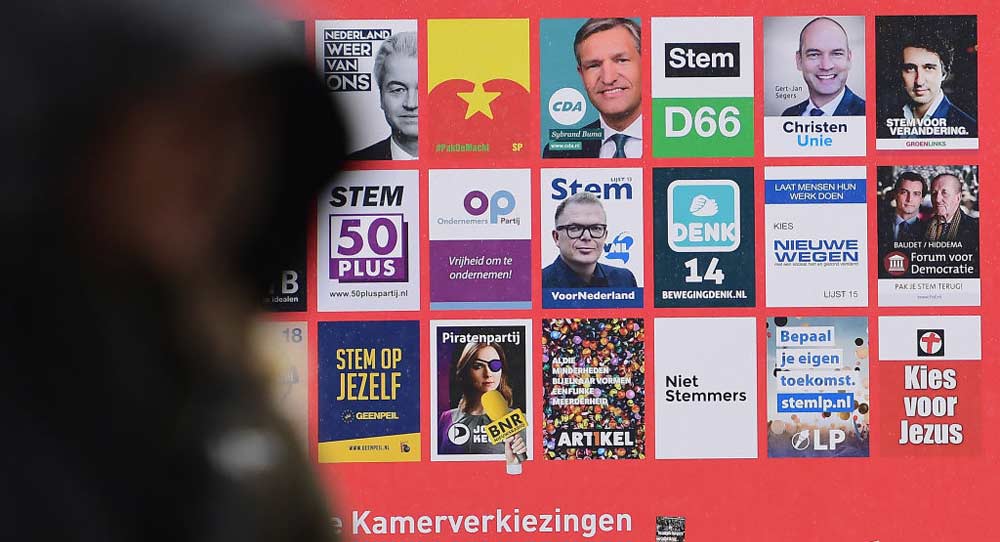

It is difficult to see the wood for the trees in a contest with 28 political parties, many of which are new and represent specific interests. Seven parties each take about 8–16 percent of the vote share in the polls. However, less than one week before the election, about half of the electorate is still floating.

In general, the Netherlands seems to have become less open-minded in recent years, and a progressive, left-wing majority in the parliament is highly unlikely after this month’s vote. The populist, far-right Party for Freedom (PVV) of Geert Wilders was leading in the polls for a long time but is now losing ground. This downward trend is caused by Wilders’s sparse appearances in public election debates, other parties’ exclusion of the PVV as a coalition partner, and the experience of U.S. President Donald Trump, who has negatively illustrated what happens when politicians try to put conservative patriotic ideas into practice.

On foreign policy and European integration, a close look at ongoing debates and election programs reveals the vast differences between Dutch political parties. At one end of the spectrum is the PVV, which argues in its one-page program for a Dutch exit from the EU, a Trump-style ban on immigrants from Muslim countries, and the termination of all development aid programs. Also on the right, the conservative-liberal Party for Freedom and Democracy (VVD) wants to remain in the EU but argues for a foreign policy based on national interests, with drastic cuts to development aid.

On the other side, GreenLeft and the Labor Party (PvdA) favor an increase in development aid and a better, if not stronger, EU. On immigration, they are milder, although the PvdA—to which European Commission Vice President Frans Timmermans belongs—increasingly points to limits in the Netherlands’ societal capacity to absorb high numbers of newcomers.

In the center, the modernist-liberal Democrats 66 (D66) party is outspokenly pro-European and in favor of welcoming refugees. Meanwhile, the Christian Democratic Appeal (CDA) is less vocal on European integration and highlights the need for a greater acknowledgment of the Judeo-Christian tradition as the cultural foundation of Dutch society.

What is different from previous elections is the attention given to defense policy. Although defense is still far from a major campaign theme, it has gained prominence in the parties’ election programs. Except for the orthodox Socialist Party and GreenLeft, all major parties want to increase the Dutch defense budget, with proposed rises ranging from the PvdA’s €400 million ($422 million) to the VVD’s €1 billion ($1.1 billion)—or even more from fringe parties.

This is well below the €2.5 billion ($2.6 billion) that is needed to reach the EU average of 1.45 percent of GDP and for which Dutch Defense Minister Jeanine Hennis-Plasschaert of the VVD has publicly argued. It is also far from the 2 percent of GDP that NATO (and Trump) has asked all allies to spend on defense. What the different budget proposals imply for the priorities for Dutch security policy and the structure of the country’s armed forces is unclear.

Immigration has become another important issue in the campaign. In a surprise test on the eve of the election, all parties were forced to take a stand on plans by the Turkish foreign minister to speak in Rotterdam on March 11 to persuade Dutch Turks to vote in Turkey’s April 16 constitutional referendum. The reaction of most Dutch parties was to denounce this move as provocative, rather than to tolerate it as an act of free speech. At stake was the question of how closely attached dual-nationality Turkish migrants are to a regime that according to most Dutch politicians is becoming unacceptably authoritarian or even dictatorial.

Eventually, the meeting was canceled by the party center that was due to host it. But the prominence of Turkish politics in the Netherlands has shocked many citizens and politicians, as it illustrates that Turkish migrants are not well integrated into Dutch society and use Turkish media as their main point of reference. The issue was particularly sensitive for the PvdA, because key people involved belong to this party: Dutch Foreign Minister Bert Koenders had called for his Turkish counterpart not to visit the Netherlands, while it was Timmermans who helped craft the much-criticized March 2016 EU deal with Turkey on reducing migrant flows.

Meanwhile, there is stunning silence in the election campaign on recent developments in U.S. politics, their meaning for the transatlantic bond, and Britain’s imminent departure from the EU. These are issues of significant impact that will result in the Netherlands losing strong allies. Europe can no longer rely on the United States as its undisputable security provider. And the UK will no longer be a close ally in the EU.

Dutch party leaders are also remarkably quiet on other big issues, such as the rise of China and its aspirations to develop a new Silk Road and Russian President Vladimir Putin’s assertiveness and potential meddling in elections in the United States and other Western countries. Nor are Dutch politicians discussing the EU’s plans for reinforced defense cooperation or its June 2016 global strategy.

Game-changing events may still take place in what has so far been a dull campaign in which small parties have attracted quite some attention and the polls have not moved much. Party leaders may keep their electoral powder dry until the very last days of the campaign. A rally between one right-wing party (the VVD or PVV) and one left-wing party (the PvdA or GreenLeft) might still emerge, as in the previous election in 2012, but the centrist parties (the CDA and D66) could absorb last-minute votes too.

With the PVV boycotted as a coalition partner and the range of possible governments narrowed accordingly, a four- or five-party center-right majority seems viable, but in coalition negotiations one can never be sure. Despite the parties’ vastly different viewpoints on European integration and immigration, the Netherlands’ election campaign gives a strong impression of a country sailing alone into bleak compromises.

Louise van Schaik is a senior research fellow and head of the Sustainability Center at Clingendael, the Netherlands Institute of International Relations. Anne Bakker is a research fellow at Clingendael. This blog post is the third in a set of guest contributions providing insights into the March 15 Dutch parliamentary election.