In November 2016, a book titled Révolution came out in France. It is not unusual for French politicians to put their ideas in writing—especially when they have ambitions for high office. But the author was a 38-year-old, little-known, former investment banker turned economy minister, who was embarking on an amazing journey to become the youngest elected President of the French republic a mere seven months later. His name was Emmanuel Macron.

Although the book wasn’t bad, most analysts either ignored or criticized it. The BFM news channel called it “a classic book,” and on the website CritiquesLibres, a reader complained that “it had nothing to do with Revolution!” Unsurprisingly, the far-left newspaper L’Humanité used the word “pompous” to describe it.Perhaps they hadn’t truly read the book, which is now a bestseller, with 300,000 copies sold and over 20 foreign editions underway. Meanwhile, due to Angela Merkel’s inability to form a coalition government two months after Germany’s federal election, it is fair to say that Macron could even claim the European leadership. After years of being seen as the EU’s primus inter-pares, is Germany’s four-times elected chancellor about to be replaced by France’s new president?

As pointed out by Laurent Bigorgne, Alice Baudry, and Olivier Duhamel, the authors of Macron, et en même temps..., a timely essay on the Macron phenomenon just published in French, France’s president is indeed a revolution himself—and a pro-European one, warmly welcomed by German elites as well as by Brussels bureaucrats.

Elected at an age when most French politicians are still building their careers, either in government or in their local constituencies, Macron saw an opportunity to step in at a time when the electorate appeared especially disillusioned. His three predecessors—Jacques Chirac, Nicolas Sarkozy, and François Hollande—had all been elected with reform-minded agendas of some kind, yet failed to deliver, either for political reasons (Chirac called a snap parliamentary election in 1997 and lost it; Sarkozy confronted the unions and failed) or for the lack of will. In Hollande’s case, it was perhaps a combination of poor economic performance following the 2008 crisis, a tense security situation due to a succession of terrorist attacks, and a lack of ambition from the ill-prepared leader.

Macron created space for himself between the November 2016 publication of Révolution and the May 2017 presidential election, write Bigorgne, Baudry, and Duhamel. “Never before had the French expressed so much defiance against their politicians, to the extent that many saw the Far Right reaching the final round of the French presidential election no matter who would be the other finalist.” Over his short political career, Macron also plainly spoke in favor of strengthening the European Union.

It is fair to say that Macron benefited from the decline of both of France’s two traditional parties: the socialist Benoît Hamon quickly appeared unelectable due to his radical ideas verging on utopia. As for the republican candidate, ex-prime minister François Fillon became a liability in February, after revelations that he had employed his wife and children for fictional jobs as parliamentary aides—a no-go area for an electorate tired of semi-corrupt politicians. Macron quickly emerged as the frontrunner.

The man was indeed lucky, but his rise and success came at the right moment for a disillusioned, if not depressed, middle class with high expectations for change. Macron is a graduate of the elite École Nationale d’Administration, but he was also an unusual breed: born in Amiens, a medium-sized city in northern France, he studied philosophy with phenomenologist Paul Ricoeur before spending several years in the private sector as an investment banker, and then joined Hollande’s team as an adviser in 2012. “Macron owes a lot to Hollande—but less for his political patronage than for his leadership failures,” assert the authors of Macron, et en même temps... .

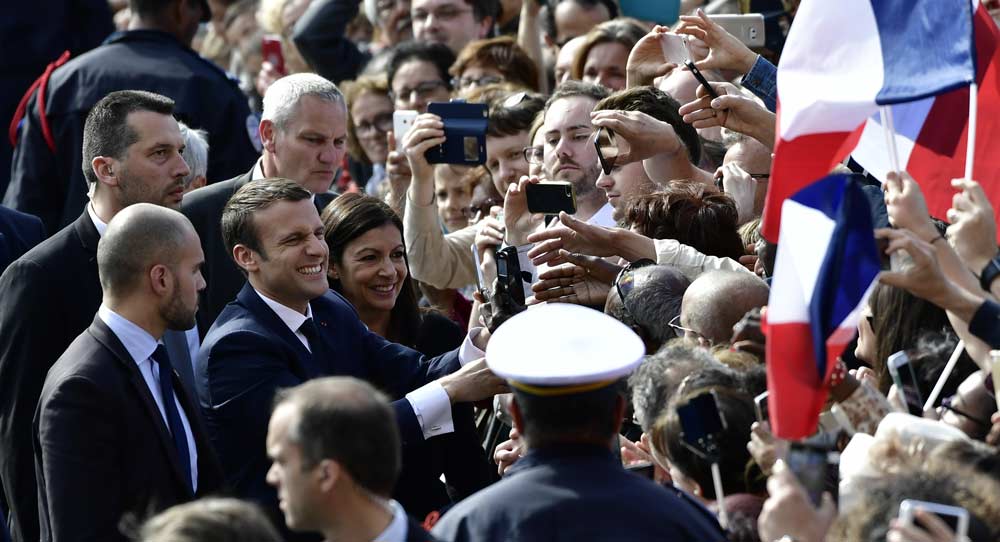

Macron was able to brand himself as a politician outside the system by creating his En Marche ! movement (which bears the same initials as his own, though the candidate’s staff explained this was “pure coincidence”), and rallying popular support among a generation of voters who had had no previous political affiliation. Unlike the National Front’s Marine Le Pen, who ended up losing both presidential and legislative elections, Macron managed to create a positive attraction—while defending both French and European values, to the relief of France’s European partners, especially Germany. In the West, where populists were on the rise, Macron became the “exception that confirms the rule:” a pro-EU politician with a positive, business-friendly discourse. In effect, votes clearly showed that a vast majority of millennials favor Macron; French expats also massively supported him.

On the foreign policy front, Macron’s seven-month presidency has been characterized by a succession of high-level visits, including by U.S. President Donald Trump and Russian President Vladimir Putin, and a general impression that “France is back.” The election of the first officially pro-EU French president since 1978 has given hope to officials in Brussels (although the German scene now appears somewhat worrying.) “We need to create a Europe that protects with a real defense policy and common security,” Macron recently said. Indeed, the launch of an EU Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO) can be partly attributed to French diplomacy, although the effort had started well over a decade ago.

Macron, en même temps... is divided in two parts: the first tells of the candidate’s rise and electoral successes in early 2017. The second describes his achievements so far. Not only did this man win 66 percent of the votes in the second round of the May 7 presidential election, destroying Marine Le Pen, who was seen as incompetent and aggressive; he also acquired a full parliamentary majority the following month, winning 350 out of 577 seats. Most of his En Marche! candidates were inexperienced politicians, who spanned the political spectrum. The result has been a chaotic first few months, ending with a party congress in November and the selection of a new leader, Christophe Castaner, one of Macron’s closest associates. In any case, it is much too early to assess the Macron presidency.

Before France can return as a European and international leader, Macron needs to make the French economy great again. According to Bigorgne, Baudry, and Duhamel, a real Macronian revolution would be to make France an entrepreneurial nation again. “France is your nation,” Macron, then minister of the economy, said in January 2016 to an audience of French entrepreneurs during French Tech in Las Vegas. Fifteen months later, they voted for him en masse.

Macron, et en même temps…, by Alice Baudry, Larent Bigorgne, and Olivier Duhamel, was published by Plon in October 2017.