Whenever there is a crisis, European Union leaders have the habit of saying that the bloc will emerge stronger. They have been repeatedly disproved of this slogan, which has lost all meaning.

The war in Yugoslavia, which led to the killing of tens of thousands during the 1990s, didn’t push the EU into developing a credible foreign or defense policy.The global financial crisis of 2008–2009 followed by the near collapse of the EU’s euro currency weren’t enough to convince European leaders to pursue more economic integration.

The war in Syria, now in its tenth year, should have shamed European leaders into some kind of action to stop the misery and killing. Instead, with few exceptions, European leaders turned inward, unwilling to take any kind of political or moral leadership.

And when that war led to refugees trying to seek safety in Europe, the reaction by several European leaders was to keep these suffering people out. To this day, European leaders cannot agree on a refugee, asylum, or migration policy.

These crises, instead of having the effect of pulling Europe closer together, have strengthened the individual member states at the expense of the EU institutions. To various degrees, each one of them has pursued its own foreign, economic, and social policies.

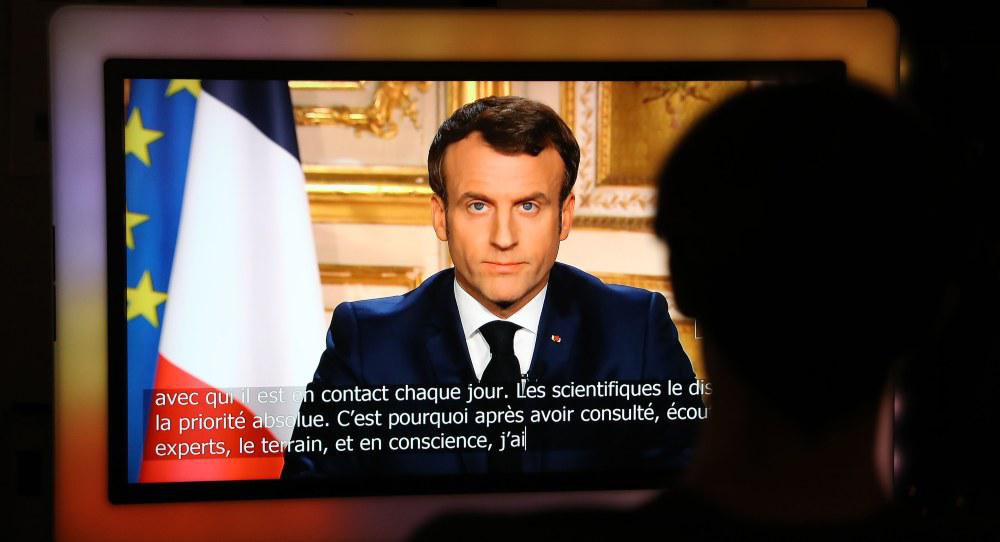

Attempts by French President Emmanuel Macron to create a more integrated Europe, which was one of his campaign slogans that got him elected in 2017, have faded away. In short, over the past few years the EU’s member states have quite happily gone their own way, even retreating into their own national comfort zones while at the same time being content to let the European Commission remain the guardian of competition and trade.

Logically, the coronavirus now ravaging parts of Italy and Spain and sweeping across the continent should be the ideal opportunity for the EU to move away from complacency and national individualism to solidarity and European integration. Instead, the pandemic, so far, has proved the opposite.

Each member state’s government has adopted its own way of containing the virus. Yes, they all have now introduced curfews and restrictions after seeing what happened in Italy. And, led by Germany, governments are opening their purse strings to support those who have lost their jobs or been forced into temporary leave. And national borders are being closed to contain the virus.

But this is not a European response. The pandemic has not generated a sense of solidarity among the member states or forced a reappraisal of the EU’s role in setting the agenda, even on something as fundamental as safeguarding the health system.

It’s all very well people tweeting their support for Italians and tweeting gratitude for the tens of thousands of medical staff. But governments and the private sector have been woefully slow in producing basic protective clothing both for their own populations and for Italy, Spain, and other countries whose health systems can barely cope with the number of infections and deaths.

Indeed, for such a rich part of the world, it is pathetic to see Russia and China be the ones supplying medical assistance to Italy and Spain. These are the very two countries that are doing their upmost to divide Europe and weaken public morale.

Russia is spreading disinformation and fake news about how governments are either lying about the virus or being incompetent in containing it. Leaders across the EU should openly criticize such campaigns and find ways to combat these insidious narratives. Meanwhile, China is adeptly using its soft power to win favors from individual European countries.

As if that wasn’t bad enough, Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán is using the pandemic to accumulate more powers by effectively bypassing the Hungarian parliament. No doubt he’ll get away with it, similar to all the other measures he has taken in recent years that make a mockery of Europe’s values.

In short, the pandemic has turned into a national—not a European—pursuit of containment.

When it is all over, a few things, hopefully, will have changed in Europe. The bloc’s health system will need a radical overhaul. This is about dealing with the rampant corruption in Bulgaria, Hungary, and Romania, the lack of planning and logistics in other countries, and the absence of coordination in terms of research across the bloc. This is about changing the meaning of security.

Investing the EU with powers over health is not the answer. It’s about governments, the private sector, civil society, and the medical-scientific profession working hand in hand across the bloc to prepare for the next pandemic or next security threat.

It’s about those four players defending, communicating, and practicing Europe’s values and democratic institutions. Without that, the coronavirus will have had the effect of consolidating national comfort zones, much to the comfort of those seeking to weaken the EU.

.png)