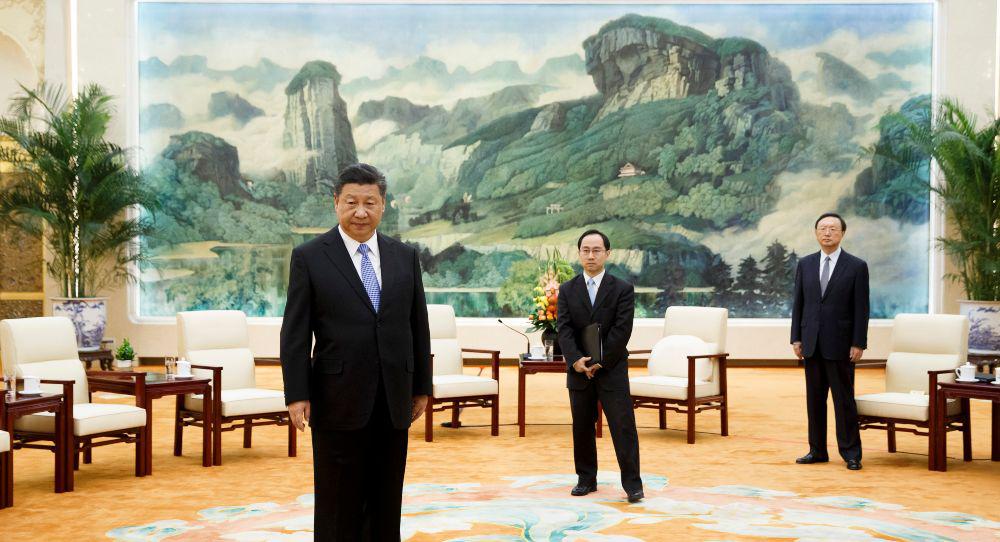

At the UN General Assembly in September 2020, Chinese President Xi Jinping made an unexpected promise: China will peak carbon dioxide emissions in 2030 and become climate neutral by 2060.

This piece of news will have resounding short- and long-term consequences on at least two fronts: the EU’s leverage in an increasingly tense geopolitical landscape and the fight against climate change itself. This piece will focus on the geopolitical aspect.

Xi’s announcement was tactical. He used the UN General Assembly as an echo chamber to posit China as a global leader on multilateralism. It is yet another step in Beijing’s strategic

institutional chess game, which it is playing particularly well.

The timing of the announcement was strategic, too. Xi made it after the EU-China summit on September 14, which featured climate change as one of several critical topics, before the U.S. presidential election in November, and before the launch of a new EU-U.S. dialogue on China on October 23. This is not a coincidence.

By making his climate ambitions clear, Xi is playing to the EU’s climate leadership goals. He aims to enhance the EU’s geopolitical stance and position China as its main partner for the future. Simultaneously, China aims to support the United States’ self-sabotage on the global scene and destabilize old alliances such as the transatlantic relationship.

By shining a bright light on climate commitments, Xi is thus pursuing three goals in the geopolitical arena:

- Positioning China as a leader of hope where prospects are bleak and where concrete delivery is fast needed. He is using the fight against climate change as a soft-power magnet.

- Taking attention away from China’s human rights abuses and aggressive economic behavior. He is aiming to make the EU more amenable to compromise in areas where China is not ready to yield.

- Courting the EU away from its old geopolitical partnerships.

Where does this leave the European Union? In an unenviable albeit influential middle-power position.

This is a good thing. If Europeans play their cards strategically, the EU could use this position to elevate the global playing field in favor of more substantial and more coordinated climate action. In doing so, it would tacitly become an orchestrating power, drawing rivals toward more cooperative frameworks over time. In short, the EU could make the climate fight the defining geopolitical issue—rather than a marginal one.

This is not an easy part to play, nor an easy one to keep. But this geopolitical casting is closer to the EU’s fundamentally stabilizing role; it plays to its strengths, its regulatory power, and its governance complexity.

And there is unfortunately no time to rehearse. The role has just been cast with the EU-U.S. dialogue on China. And the first act indeed confirmed that climate issues set the scene.

On October 21, U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo was provoked into reacting—as a matter of priority in his anti-China campaign—to Beijing’s release of a fact sheet on environmental damage caused by the United States. In his response, Pompeo listed China’s poor record on greenhouse gas emissions, plastic pollution, and biodiversity plundering.

Ironically, the United States has cornered itself into making climate change a key aspect of its rivalry with China. As a result, the EU can now engage substantially with the United States on climate action, regardless of the result of the U.S. election.

That in itself is a major win. A race toward decarbonization is now central to the U.S.-China rivalry, leaving the EU with a potential double role as both active player and arbiter. This is a geopolitical chance delivered to European leaders on a silver platter with immediate rewards. The EU must embrace it.

And Europe will be key in navigating a global order that is changing structurally at an accelerating pace. Setting up the right cooperation frameworks with the United States on one side and China on the other will be a crucial balancing act. Both countries are needed—and the EU cannot become complacent, even if Democratic candidate Joe Biden wins the U.S. election.

But even more importantly, it will be critical to deepen partnerships with countries and blocs in Africa, the Middle East, Latin America, and Central and East Asia that are eager to free themselves from China’s and the United States’ hold. There are two reasons for this.

First, this will create safety cordons around the global instability that the rivalry between these two powers generate. Second, this will help accelerate global climate action. Geopolitics are currently driving the climate transition; it should be the other way around. Neither the United States nor China have integrated climate change in their long-term plans as the defining issue of our time.

If we do not act systemically on climate change and on ecological disintegration at large, there simply won’t be any big-power competition to speak of in a matter of decades.

The EU must identify its new geopolitical value proposition—one that is different from the old liberalization agenda of the United States’ and different from the “ecological civilization” agenda of China’s Belt and Road Initiative.

Neither of them fit the global imperative for bringing the human footprint back within planetary boundaries. If the EU is to endorse a middle-power position, it must offer a middle way—and one that truly supports a coherent ecological diplomacy.

The EU’s Green Deal is only the beginning in a larger set of transitions that will transform the dynamics of European politics and global geopolitics.

Carnegie Europe is grateful to the Open Society Foundations for their support for this work.