For four years, the EU and its member states showed remarkable backbone in their determination to uphold the 2015 nuclear deal with Iran. It was not enough to keep the agreement fully alive, but it was more than many—including one (now former) U.S. president—would have expected from the old continent. It’s therefore even more surprising that the Europeans are not now brimming with energy to bring together the world’s two main enemies of the last forty-two years: the Islamic Republic and the United States. Yet, that is exactly what Europe should urgently be doing.

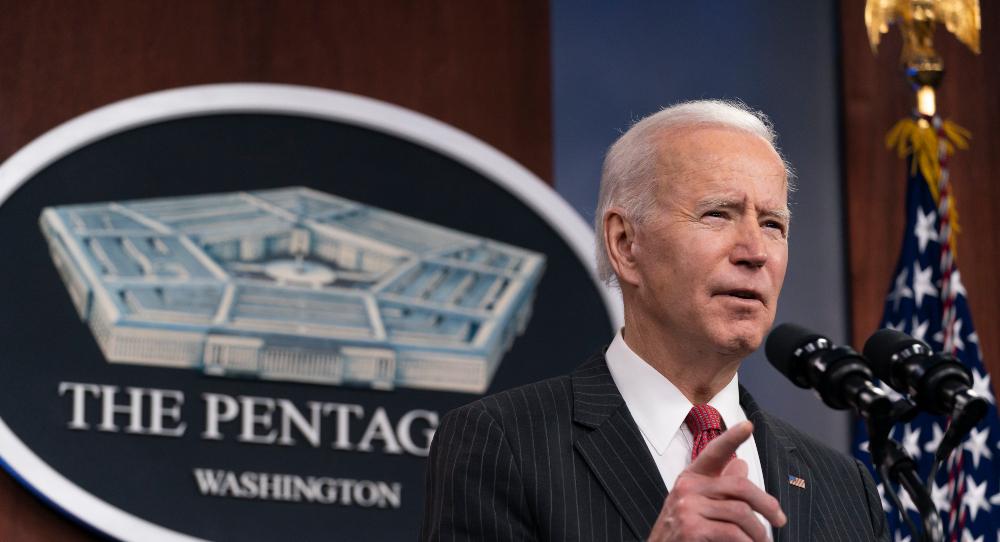

The high hopes associated with the election of U.S. President Joe Biden had already turned into low expectations by his January 20 inauguration. Unlike with his promises to rejoin the Paris Agreement on climate change and reestablish cooperation with the World Health Organization on day one, Biden and his advisers have been clear that Washington will not simply return to the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), which his predecessor left in May 2018. Instead, they expect Iran to come back into compliance first, just as America’s hawks have demanded that Washington must not give away the sanctions leverage created by the previous administration.

The Iranian government, for one, sees things the other way around. For very principled reasons, Tehran is unlikely to make concessions given the deep mistrust that Washington’s unilateral withdrawal has created. After years of maximum pressure from the United States, policymakers in Tehran even speak of compensation for U.S. sanctions—if only to make the point. What’s more, allowing the United States back into the JCPOA includes handing Washington the power to snap back all international sanctions in the future—possibly as soon as 2025, when there may be yet another new president in the White House.

To add urgency to the stalemate, Iran’s nuclear advances keep the clock ticking. Breakout time—the period a country needs to amass enough fissile material for one atomic bomb—is now seriously reduced. That time was calculated to be one year when the JCPOA entered into force in early 2016; five years and two U.S. presidents later, it is estimated to be down to four months. Earlier in February 2021, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) reported that Iran had produced low amounts of uranium metal, a component with military use that is banned under the JCPOA. On top of that, hardliners in Iran’s parliament have set a February 21 deadline for some sanctions relief, otherwise the government will be forced to suspend parts of the IAEA’s verification authorities.

Against this backdrop of both increased stakes and heightened difficulties, the Europeans need to outline a common course with the Biden administration—and fast. Yet, they again appear to be waiting for the United States to take the initiative. Of course, they had to let the new U.S. secretary of state, Antony Blinken, enter office before officially reaching out to him. A first conversation between the British, French, and German foreign ministers and Blinken took place on February 5.

However, with weeks rather than months to come up with a concrete proposal, the Europeans could have made a more forceful attempt to put the EU in the driver’s seat. Oddly enough, it was Iran’s Foreign Minister Javad Zarif who called on the EU as the chair of the JCPOA’s Joint Commission, which monitors the accord’s implementation, to mediate a U.S. return to the deal. Not only could this proposal have come from Brussels itself, but the wrong person also responded to the call: French President Emmanuel Macron suggested himself as an “honest broker.”

The Europeans don’t need the U.S. secretary of state to draft a to-do list for them. Instead, they should channel their frustration over Iran’s diversion from the JCPOA into concrete demands and timelines for a sequenced return to full compliance by all signatories. In this context, it doesn’t hurt—and, indeed, it would bolster the EU’s role as a neutral mediator—to remind Washington of the need to make the first move. This could be the simple but highly symbolic revocation of the May 2018 executive order that sealed Washington’s withdrawal, and it could be done by Biden when he speaks on February 19 at this year’s virtual Munich Security Conference.

Moreover, it doesn’t suffice for Europe to work behind the scenes; Europe has to win the public discourse, especially given the hardening of debates in both Tehran and Washington. Therefore, the Europeans should press all partners on the delivery of humanitarian aid by boosting the near-defunct Instex trade channel and greenlighting the pandemic relief loan Tehran requested from the International Monetary Fund. And they should explore avenues for regional de-escalation by mulling broader talks—not about Iran’s nuclear program but about the security concerns all sides have, from missiles and militias to drones and domestic unrest.

Precisely because the beef is mainly between the United States and Iran, Europe has a role to play as a go-between. The Europeans should do so in close consultation with Washington, but not at the latter’s behest. Europe can’t hide, and it has little time to lose.

Correction: The piece misspelled the name of the secretary of state. It is Antony, not Anthony.

This blog is part of the Transatlantic Relations in Review series. Carnegie Europe is grateful to the U.S. Mission to the EU for its support.