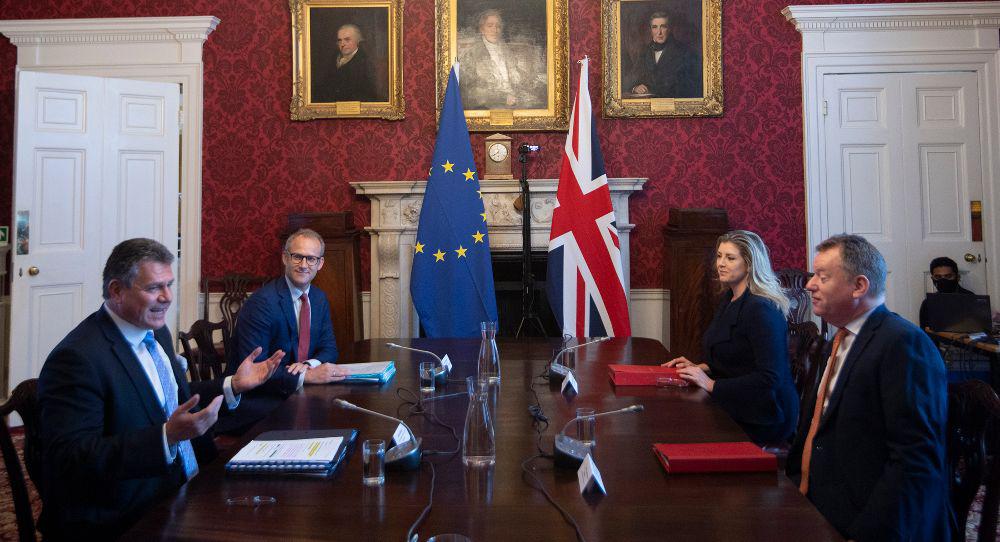

For a while this spring, British ministers seemed to be edging toward a deal with the European Union on the Brexit issues that still divided them. Public grandstanding died down as confidential talks were held with little leaking.

They didn’t last. The fundamental gaps between the two sides could not be bridged. Megaphone diplomacy has returned. In the past few days, Lord David Frost, Britain’s Brexit minister, has denounced a crucial aspect of the painfully negotiated agreement that set out UK-EU relations following Brexit.

The problem—and we are edging toward a situation in which “crisis” would be a better word—stems from the inevitably singular status of Northern Ireland.

To recap, for those of you at the back who have not been paying attention, the province is part of the UK; it departed the EU at the same time as England, Scotland, and Wales. However, one central feature of the hard-won 1998 Good Friday Agreement, which ended decades of conflict, was that the 500-kilometer border between Northern Ireland and the Irish Republic would be completely open. Goods and people would be able to cross the border freely.

This meant that post-Brexit there could be no customs checks on the only land border between the UK and the EU. So: how could any trade rules be enforced? The answer was provided by the Northern Ireland Protocol, a painfully negotiated deal between London and Brussels that sought to square the circle. Northern Ireland would remain in the EU’s single market. But in order to prevent traders circumventing the UK-EU trading rules, there would be checks on goods crossing the Irish Sea between Northern Ireland and mainland Britain.

It is these checks that are now the main source of friction between London and Brussels. They came to a head in what has become known as the “sausage war”. EU rules stipulate that meat entering the single market must be frozen. As Northern Ireland has remained in the single market, British supermarket chains sending sausages—and other meat products—to their stores in Northern Ireland can no longer send them chilled, as they used to do pre-Brexit; they must freeze them first.

These new rules were supposed to come into effect on July 1, 2021, following a grace period to allow companies to adjust and a new system of official checks to be installed. This has now been extended by three months, while talks continue to solve the problem. A solution would entail the UK accepting the new rule or the EU agreeing not to enforce it, or some compromise being negotiated.

Which brings us back to Lord Frost’s latest intervention. He told the Sunday Telegraph that the three-month truce was merely a “sticking plaster,” that “there is a long list of issues thrown up by the way that the protocol has been implemented,” and that it “doesn’t reflect the balance that was in the Good Friday Agreement as it was intended to.”

Those remarks are significant for two reasons. The first is that Lord Frost went public at all. If he had expected the three-month truce to lead to a new agreement, he would have said little or nothing—and certainly nothing as provocative as he did.

The second, and increasingly important, point about his remarks is that he feels the need to attend to sensitivities in Belfast as much as to his interlocutors in Brussels. The past few weeks have seen the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) start to fall apart. Under an agreement hammered out in 2006, the first minister is nominated by the largest unionist party in the Northern Ireland Assembly. (That will remain the case until or unless nationalists in the assembly outnumber the unionists.) The DUP is currently that party.

Arlene Foster had been DUP leader and first minister since 2015, but she was deposed in May by her own party. High among the issues that had inflamed many DUP voters who had taken to the streets was her perceived failure to fight hard enough to scrap the Northern Ireland Protocol and remove all checks on trade between the province and the rest of the UK.

The party narrowly voted for Edwin Poots, a more hardline unionist, to succeed her; but after just three weeks, he also fell out with a large section of his party and was forced to resign. He was in turn succeeded by Jeffrey Donaldson, an experienced politician but one with little room for manoeuvre. One of his first pronouncements as DUP leader was to demand that the Northern Ireland Protocol be scrapped.

Which brings us back to Lord Frost. Legally, he can ignore Jeffrey Donaldson’s demand. Politically, he can’t. For twenty-three years the Good Friday Agreement has been the story of fragile success. The UK’s membership of the EU helped to underpin that success, for it ensured economic harmony across the island of Ireland and prevented the need for a border.

At the time of the Brexit referendum, few people heeded those who warned that Britain’s departure from the EU might spark a crisis in Northern Ireland. Today the peril is obvious.

So what now? If the EU remains determined to protect the single market and the UK continues to insist on its right to set its own rules, especially on food safety—the casus belli of the sausage war—then compromise looks somewhere between hard and impossible. The coming months may well see more bitterness and friction in UK-EU relations—and threaten the fragile 1998 settlement that has largely kept violence at bay in Northern Ireland.

I would far prefer to end on a more upbeat note. But, as someone wise once warned, the existence of a problem does not necessarily imply the existence of a solution. And for the moment, megaphone diplomacy is making a tough problem even worse.