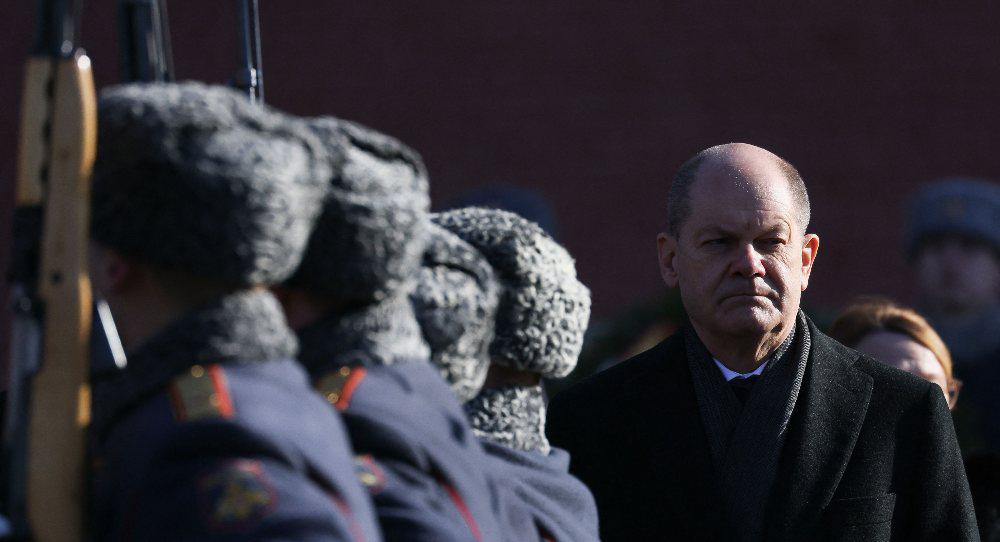

At least Olaf Scholz went to Kyiv first, before traveling to Moscow on February 15.

The German chancellor’s visit to Ukraine was part of his diplomatic efforts to avert a new Russian attack on the country.

Despite Moscow’s repeated denials that it has intentions of invading Ukraine, it has stationed around 130,000 troops on the country’s eastern border. It is holding exercises in neighboring Belarus. It has deployed warships in the Black Sea. While Russia insists it is NATO that poses a security threat to Moscow, what Russia is doing to Ukraine is a major security threat. The country is almost encircled by Russian forces.

Averting a war is in the interest of all EU and Eastern European governments. Ukraine has already been scarred several times by bloodshed. The country has undergone immense suffering—from the Soviet-imposed famine of the 1930s and the appalling destruction during World War II by Nazi and Soviet troops, to the deaths of over 13,000 people in 2014 after Russia invaded Eastern Ukraine. With Russia’s military buildup, there seems to be no end in sight to this catalogue of woes. Unless Germany changes its stance.

Over the past few months, much has been written about Germany’s ambiguity toward Russia. This ambiguity is partly based on the complex history that has shaped the relationship between these two countries. But there is only so far that history can go in explaining Germany’s continuing reluctance to spell out what is taking place in Eastern Europe in general and Russia in particular. Eastern Europe is being contested.

As seen by Moscow, countries in the EU’s Eastern neighborhood, including Ukraine, Belarus, Moldova, Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan, should remain in Russia’s sphere of influence. This is a region that should not move closer to the EU or NATO. It is a region that should be Russia’s security buffer zone.

Were all this to become a reality, Eastern Europe would become a highly unstable region that would deal a heavy cost to both Russia and the EU. That is why Germany has to take a stand about the region’s future and Russia’s role.

Berlin has a moral, political, and economic responsibility to do so. Moral because of what happened during World War II. If President Frank-Walter Steinmeier can argue that Germany bears a special responsibility toward Russia, as he did in 2021, why can’t he say the same about Belarus and Ukraine? Just read Timothy Snyder’s Bloodlands to appreciate how the populations of these countries were massacred during the early 1940s.

The political responsibility complements the moral one. Then there’s the economic aspects. German industry has reaped the benefits of low-cost labor and the geographical proximity of these countries for doing business. Total trade to its Eastern partners increased by 20 percent in 2021 to over €500 billion ($567 billion).

The silence by Germany’s powerful and influential Ost-Ausschuss—or Eastern Committee—to what has been taking place in Belarus over the past two years and how Ukraine is being intimidated today is shameful.

As for German industry’s attitude toward Russia, the ties with their Russian counterparts, particularly President Vladimir Putin and his entourage, have become so close that they influence Berlin’s policy toward Russia.

It’s rare to read or hear from German companies that are doing business in Russia about the erosion of human rights, the closure of non-governmental organizations, the imprisonment of Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny, the banning of human rights group Memorial that became such a special organization for many Russians who wanted a reckoning with the Stalinist era.

This reticence about Putin’s Russia is even harder to justify given the Russian cyberattacks on the German Bundestag, the murder in 2019 of a Chechen exile in Berlin, and the attempt to kill Navalny with a chemical agent. If German industry chiefs spoke out clearly about what is happening in Russia today, it just might toughen the stance of Scholz’s Social Democratic Party and weaken the influence of its Russia supporters.

The latter never question the kind of system being built in Russia and how it bodes ill for Eastern Europe. These countries, with difficulty, are trying to move toward democracy and closer to the EU.

Russia’s support for Alexander Lukashenko’s regime in Belarus, its continuing meddling in Moldovan politics, its intimidation of Ukraine, and its influence in Armenia and Georgia are about thwarting the Western direction of these countries. They are about putting the brakes on building democratic institutions.

Germany alone cannot influence what happens in Eastern Europe or Russia. But because of its position in the EU and relationship with Russia, it has the economic strength and should have the political compass to take the lead. That leadership requires a political will to link diplomatic efforts with substantial pressure on Russia. Above all, it means Germany’s political and economic establishments supporting the aspirations of Eastern European citizens.