Thorsten BennerCo-founder and director of the Global Public Policy Institute (GPPi)

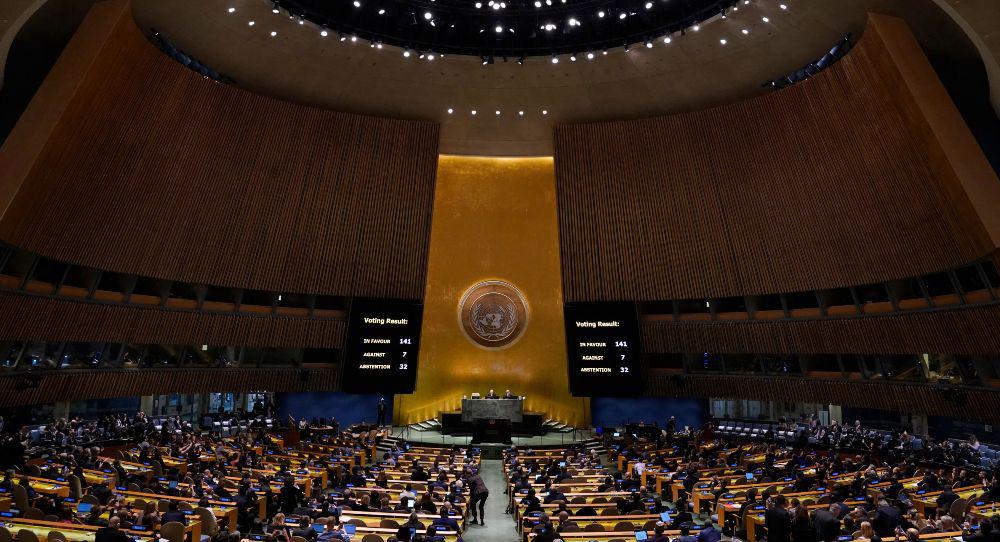

Russia’s war against Ukraine is a regional war with global implications. In the struggle for global opinion “the West” is failing in many among the diverse set of nations labeled the “Global South.” Even in many countries that voted in favor of Ukraine at the UN General Assembly, the narratives on the war Russia and its sidekick China are peddling find a sympathetic ear.

This should not come as a surprise given these countries are united by one thing: the view that “the West” and especially the United States and NATO have little credibility. In each case it is a different mixed bag of ideology, economic interests, dependencies, geopolitical concerns, and general rejection of sanctions as an instrument that leads them to not criticize or even side with Russia.

Moral indignation is not a very effective response. Rather, Europeans need to invest more in dealing with the global economic fallout of Russia’s war and in better countering Russian and Chinese propaganda. Rather than framing the war as struggle of democracy versus autocracy, they should make defending sovereignty and territorial integrity and going against Russian imperialism and colonialism the priority. If Europeans are self-critical of their own track record on these, they will be more convincing.

Jędrzej CzerepHead of the Middle East and Africa programme at the Polish Institute of International Affairs (PISM)

A simple cartoon scene is being reproduced all over Burkina Faso’s social media. Two tables are being displayed: a long line of donors queue to the first one, with a Ukrainian flag and a banner reading “6 months of war”; the second table, with a Burkinabe flag and “6 years of terrorism” banner doesn’t attract anyone.

In Congo you can see the same cartoon but with a Congolese flag instead of a Burkinabe flag, and so on.

It tells us something.

Before expecting people from Africa or the Arab World to take up Ukraine’s case as theirs, we must ask ourselves if we are ready to apply the same decisiveness in defense of human life and standards everywhere. If we fail the most lively and resilient pro-democracy movement in the world today—the Sudanese one—by imposing a Minsk-like settlement that only rewards the aggressor (the junta in Sudan’s case), its activists won’t be eager to express solidarity with Ukraine anymore.

Here is the key to explain Ukraine’s and the West’s inability to win outright support in the Global South. Russian arguments, as misleading as they might be, fall on fertile ground when they refer to a critique of the unipolar world or Western double standards. To challenge pro-Russian voices, one would risk being seen as going against some of the legitimate and prevalent local concerns. That keeps potential sympathizers silent. Like it or not, looking from Yemen to Mozambique, the Ukraine war doesn’t seem that unique and transformative as it does looking from the West.

Marta DassùSenior advisor for Europe at The Aspen Institute

No, this is not a global war: many of so-called neutral countries, including India and South Africa, do not see it as their “own” war—but rather as a war between Russia and the West being waged in Ukraine.

And yet, some of its repercussions are indeed global: food and energy security, the future of the rules-based international order. What could still turn the Russian invasion of Ukraine into a global war is the China variable: if Beijing were to intervene with arms deliveries to Russia, then the current conflict would morph into a test of strength between Western democracies and today’s major autocracies. For now, this is not happening and remains unlikely, given the importance China attaches to its relations with the Western economies.

An additional factor limits the spillover potential of this war: most members of the “Global South” simply do not view Russia as important and powerful enough to justify classical forms of “balancing”—which is instead the more immediate concern for the Europeans on a regional scale, being tackled largely by NATO.

In short, the war in Ukraine is not World War III, and there are enough reasons to think it will not evolve into that.

Mamane Bello Garba HimaResearcher at the Laboratory of Studies and Research on Economic Emergence at the University of Abdou Moumouni, Niger

It looks like everything the world experienced at the global level is not a good thing. Indeed, while in February 2022, the world was getting over COVID-19, Russia imposed an unjustified war to the world by unilaterally invading Ukraine.

This is a global war because as with every geopolitical bad decision, the world bears the burden: food insecurity, energy crisis, and so on. Unfortunately, for now, third parties—the EU, the United States, and China, for example—are divided on how the war should end: winners versus losers or those looking for peace?

In the Sahel, there is a perception that Europe’s current position on this war amounts to a double standard. Indeed, when the United States invaded Iraq and Afghanistan, war tanks or funds were provided not to those countries’ victims but to the invader.

For their own future world leadership, European governments should build their policies and positions on a genuine base—not necessarily one of a U.S. vision. Regarding this war in Ukraine, the EU should make a clear distinction between the votes at the UN General Assembly from its allies in the Sahel, and the public perception in the Sahel.

Nicholas KaridesDirector of the Institute for Mass Media at the Universitas Foundation, Cyprus

Yes. Not just in terms of the growing engagement of parties external to the conflict, or the scope and repercussions of the war itself, but for a key factor that both weaponizes and torments parts of the globe often without their knowledge: the global information war.

The war is being fought on the ground, where people are dying and being displaced. But it is also being fought relentlessly in our media. Long before boots had landed on the ground, long before Crimea was annexed, Russia with customary military ruthlessness confused, unsettled, and divided public opinion worldwide. It infiltrated with soldierly precision the tech platforms owned by the West. Its troll mercenaries captured key outposts from where they surveyed and targeted the globe’s information intake, stifling and gunning down any resistance on the planet’s public information squares with propaganda and noise. The platforms proved incapable and were often unwilling to intercept the Kremlin’s distortionary attacks.

Well before Ukraine was calling for tanks on the battlefields, scholars and experts had been calling for fact-checkers on the big tech vistas. It is a global war because Russia’s proxy views are now embedded worldwide, booby-trapping our entire information sphere.

Andrei KolesnikovSenior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

What is happening is a global conflict. This is not simply because Putin himself declared the invasion of Ukraine a defensive war against the collective West. But because Putin’s war destroyed the world order, the rules that had been polished for decades and demolished the achievements of Russia itself in entering the concert of civilized countries. Everything that had been built for years collapsed in one day.

This conflict is so large-scale that it changes not only trade, economics, logistics, and politics, but also the psychology and anthropology of entire nations. The Ukrainians have acquired their own identity: a positive one, a European one, and a negative one, based on the aversion to everything Russian.

The Russians—not all of them, but many—who are returning in terms of political culture and amorality to archaic imperialism, have not found their identity, but have lost it. Russia is so significant that this process has global meaning and affects the whole world—its attitudes and behavior. And the conflict also shows who is for humanism, who is ready to profit from war or make compromises, because for some reason these countries need a good relationship with Putin.

Gilles Olakounle YabiPresident of WATHI, Senegal

The war has a large and still not fully determined impact on all the continents and so it can be considered a global war. Beyond the violation of Ukraine’s sovereignty and blatant breach of international law, there are also many geopolitical dimensions that cannot be ignored: rivalry between Western powers/NATO and Russia, competition between the United States and China for global leadership in the future, the Western alliance versus BRICS.

It is clear that this is not only about defending Ukraine’s sovereignty, its borders, and its peoples. The diverse positions of the countries in Africa as in Asia and Latin America on the war do include consideration of their existing diplomatic relations and security cooperation with Russia, and of the global geopolitical and economic implications for their own security and economic interests.

So, the fact that the war is a global war does not mean that the reading of the war is the same from one place to another, and that the choice of each country to vote in one way or another, or to abstain from voting a UN resolution on the war, is not guided by a variety of considerations and the perception of their national interests, beyond respect for principles and values.

Martin PlautSenior research fellow at the University of London’s Institute of Commonwealth Studies

The Ukraine war is not a global war, but it clearly has global implications. For many—particularly in the global South—other issues, including climate change and their own conflicts, are far more important. It is for this reason that they resent being “asked to take sides” despite having signed up to the UN Charter which requires all members to defend the territorial integrity of all nations.

Beyond this, their response reflects the increasingly effective use of soft power by China and Russia, as well as hard power exerted by both states either via the Wagner group or territorial expansion, as seen in Taiwan. This is a complex question not easily responded to with a yes or no answer.

Kristi RaikDeputy director of the International Centre for Defence and Security, Tallinn

Russia’s war on Ukraine obviously has strong global implications. Nonetheless it is primarily a war over the European security order, with existential importance especially for European neighbors of Russia but also for the EU and NATO. It is perhaps unavoidable that there are countries in the Global South that see the war differently from the West and avoid taking sides.

Certainly it is not just a matter of communication, that is, Russia having been more effective in spreading its narratives than the West. The interests of, say, India or South Africa are different from Western interests.

The outcome of the war will influence the balance of power between the West and Russia, and the West and China. But even Ukraine’s victory won’t bring us back to the post-Cold War era of U.S. hegemony when the liberal rules-based order was at its strongest. What can be saved by Ukraine’s victory is a rules-based security order in Europe—an order that will exclude Russia for a long time to come and defend European states against the Russian threat.

The Western focus should stay on working toward Ukraine’s victory rather than trying to forge a global consensus on the war. The former is attainable, the latter most probably not.