This should be Europe’s chance.

When Joe Biden bowed out of the U.S. presidential race there was a palpable relief in most European capitals.

As support for Biden dwindled, even within his own party, commentators—and leaders—across Europe grew increasingly anxious about Donald Trump’s potential return to the White House.

They remember the four years of his presidency. Between 2017 and 2021, Trump bashed Europe, especially Germany. He bashed NATO. He bashed the EU’s soft power and its values. He much preferred leaders who defended conservative principles, who were anti-immigration, and who defended national sovereignty. Hungary’s Viktor Orbán was, and is, one of his big fans.

Europe’s relief about Biden dropping out of the race is misplaced. The outcome of the U.S. election remains unclear. And once again, regardless of the outcome, Europeans are unprepared for the tectonic shifts that will be taking place in the United States.

European leaders have had many warnings about the imbalance in the transatlantic relationship. Trump amplified what previous administrations had told Europe: it must stop taking America’s security umbrella for granted. It must spend more on defense and take its own security seriously. It must stop free-riding on its transatlantic ally. It must match its economic strength with political ambition.

French president Emmanuel Macron understood those messages. Time and again, he told Europeans to be prepared for “the day after.”

Macron was not being apocalyptic. In his recent speeches and interviews, he warned about Europe’s vulnerability in terms of its values, democracy, and Europe as an idea. His implicit message was that Europe had to defend itself against internal and external threats and against political parties seeking to challenge the essential architecture of the EU. No other European leader was as blunt and clear-headed about Europe’s weaknesses and how it was sleepwalking into crises rather than protecting what Europe—as part of the West— represents.

The West is rooted in democracy, free elections, freedom of the media, the rule of law, an independent judiciary, and accountability. It is about a perspective and a system that is contrary to authoritarianism.

If it was not attractive as a system, why would people across the world protest for human and civil rights? The latter are universal. They are not Western concoctions as its opponents claim. They need to be defended, and confidently.

Defending what Europe and the West stands for is connected to what is happening in the United States. U.S. leadership is being challenged by China, especially in in the Middle East. Israel’s war against Hamas is not confined to Gaza. Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has long regarded Iran as the biggest threat to his country. His decision to bomb Iran-backed Houthi targets in Yemen signals the wider, regional implications of the war in Gaza.

Containing the conflict will demand U.S. and Arab leadership. Don’t count on the EU. It is reduced to a bystander in the region. Instead, U.S. state and defense departments will have to mediate even though the country will be completely preoccupied with domestic issues.

With a different lens, Biden’s withdrawal from the presidential race encapsulates another element to Europe’s vulnerability.

Biden is the last truly Atlanticist U.S. president. His career, his experience in foreign policy, and his age made him an Atlanticist that believed in the enduring bonds between the United States and Europe. A younger generation does not have that institutional memory or connection with Europe.

Those bonds—exemplified after 1945 by U.S.-led multilateral institutions such as NATO, the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, the United Nations and all its subsidiary bodies—are in poor shape. The post–1945 and post–Cold War eras in which the West naively believed it could prevail in perpetuity are ending.

Europe is not prepared for this. Neither Europe nor the United States are modernizing these institutions. It is China, backed by Russia, that is trying to reshape, replace, or disrupt them.

It is hard to see how Europe can respond.

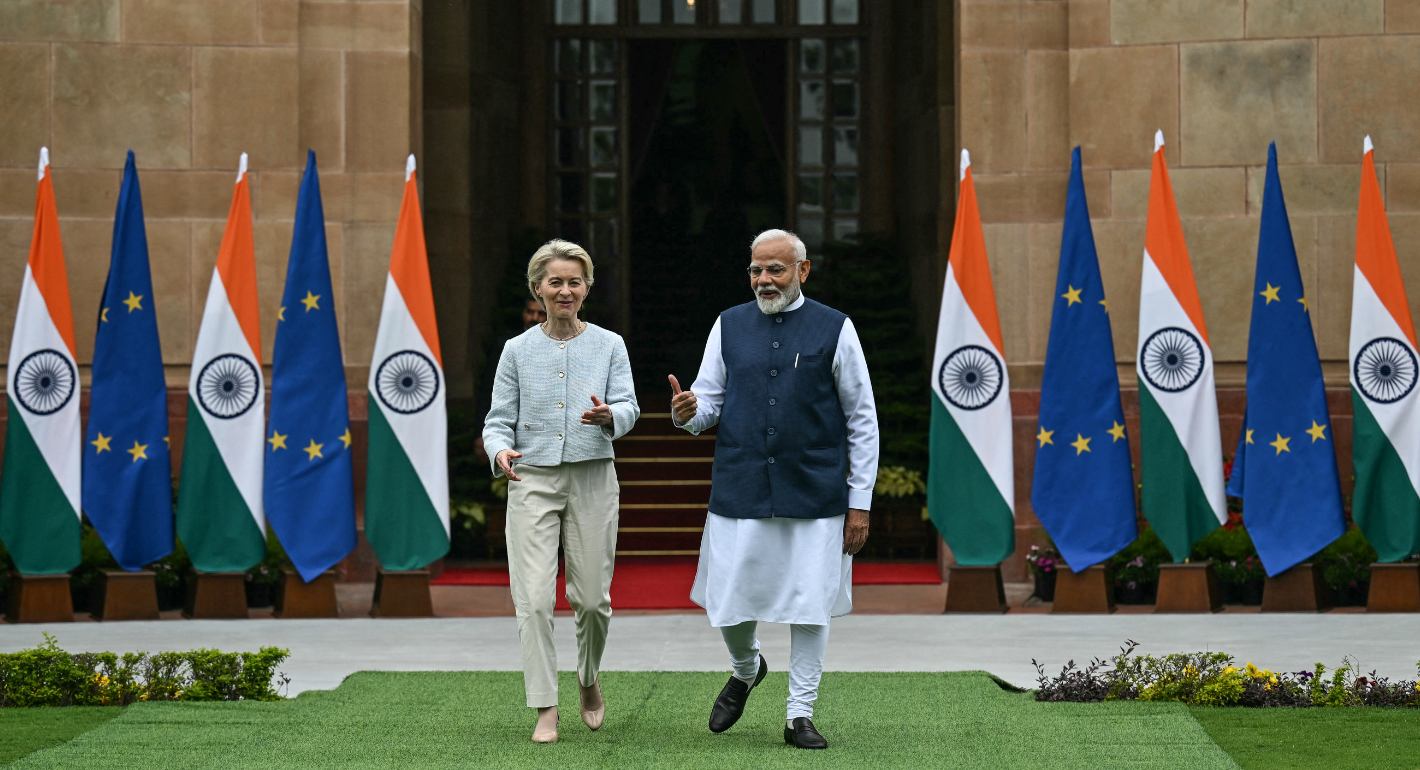

European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen wants the EU to have a defense chief and a collective defense spending policy. For her, Russia’s war against Ukraine shows why that is needed. Not all member states are convinced, however. Defense remains a national and sovereign issue.

Some member states want a union that does away with unanimity and veto rights on foreign policy issues. They want a more integrated Europe instead of an EU beholden to the member states.

Essentially, at issue is Europe. The EU’s twenty-seven member states don’t agree on the union’s direction. More political and economic integration would make sense. But several countries want to regain more sovereignty at the expense of making Europe more capable and ready for “the day after.”

With the United States so focused on November 5, Europe has a chance to step up. Unfortunately, with the exception of a weakened President Macron, leaders in Europe, especially Germany, lack the courage to explain and do what is needed.

* Strategic Europe goes on summer vacation on July 24 and will return on September 3. We wish all our readers, contributors, friends, and colleagues a safe, healthy, and restful summer. ~ Judy Dempsey