For a president with a severe domestic political crisis of his own making, France’s Emmanuel Macron seems to be getting his international mojo back. And not through performative speeches but rather through diplomatic action.

Riding high after the success of the Paris Olympics, Macron seems to have recovered from his failure in February 2024 to overcome Germany’s opposition to a more robust European stance on Ukraine, as well as a year-long publicly antagonistic relationship with Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu.

Meanwhile, he has vastly improved his coordination with Poland and the Nordic and Baltic states as they form a nascent EU defense nucleus and work on robust European security guarantees for Ukraine. He has also gotten the most time with U.S. President-elect Donald Trump of any leader so far. Even in the wars in the Middle East, Macron has managed to preserve a role.

This is the paradox the French Fifth Republic presents for its citizens and Europe: The country is reeling from a historic fiscal crisis and political instability not seen since before World War II, while Macron, the politician most responsible for the situation, is scoring international successes. But though he has managed to recover some maneuvering space on the world stage, his country’s unsustainable shambolic finances are catching up with him fast, and could have dire consequences for the EU.

There’s been a notable shift in the French president’s approach lately. Now in his seventh year as president, with an established global standing, he has been making less grand speeches and focusing more on creating operational levers.

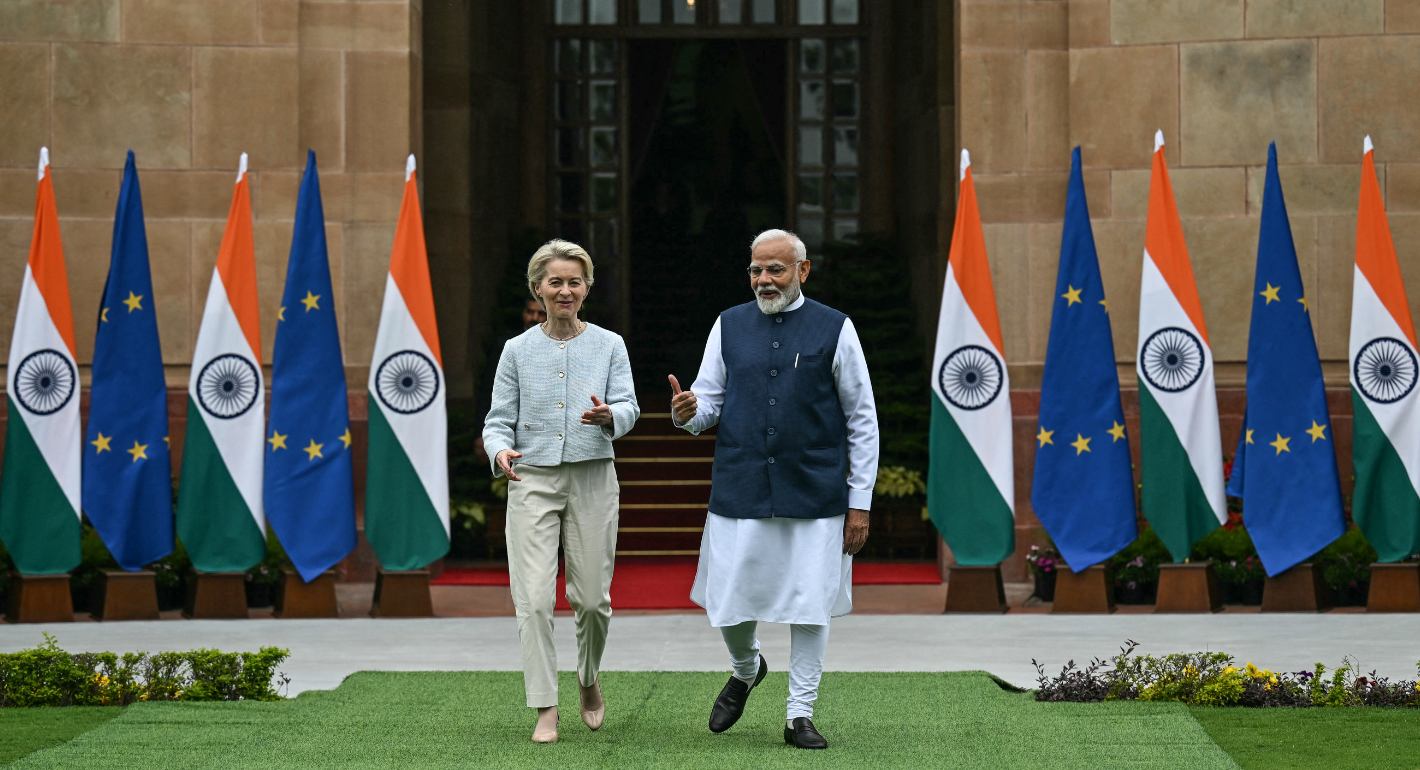

Macron’s counterparts have taken note and some are liking what they’re seeing—though they are also anxious and puzzled by the self-inflicted domestic political crisis he plunged France into when he dissolved parliament in June. In recent days he has also suffered a double setback: The French government collapsed and European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen announced the conclusion of the Mercosur trade deal despite his objections.

Notwithstanding, Macron has managed to pull off diplomatic maneuvers his European peers struggle to land even in quiet times, projecting an image of confidence and control.

As the government was collapsing in France, Macron was in Saudi Arabia announcing a strategic partnership with the kingdom, progress on a potential mega sale of Rafale fighter jets, and an agreement to co-host a summit in June 2025 that could become a watershed moment for the recognition of the State of Palestine.

One week prior, France wrestled its way into the U.S.-mediated ceasefire deal between Israel and Lebanon. The United States and Israel, for different reasons, had both at different moments tried to exclude it, but with Lebanon attached to French inclusion, Paris maneuvered and succeeded. And it wasn’t about simply putting their name to the deal.

France has ensured it has eyes and a say in a conflict which, if not controlled, could have dire consequences for Europe. It has provided life-saving immediate assistance to the Lebanese by being the first country to deploy a unit of military engineers to assist with clearing the massive destruction of villages by Israel in southern Lebanon as well as deminers.

That France had to issue an ambiguous statement on the International Criminal Court’s arrest warrants against Netanyahu was a reflection of the reality of power dynamics on the ground, and a lesser of evils, instead of the capitulation some have portrayed it to be. It does not preclude the independent French judges from enforcing the arrest warrant if Netanyahu comes to France.

Finally, as many world leaders gathered in the magnificently restored Notre-Dame Cathedral, after a five-year repair that defied the odds, Macron turned Paris into an effective diplomatic speed date. He managed to convince Trump to hold a tripartite meeting with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky. It was the most substantive and useful meeting to date on next steps.

Other foreign leaders also took the opportunity to either informally introduce themselves or reconnect with Trump. This showed a new side of Macron as a leader that convenes and facilitates for others rather than hogging the limelight.

Despite these successes, Macron cannot escape his flailing domestic legacy and will need to find a way to right his wrongs if he is to harness the full potential of his country. In the immediate short term, he seems to be getting ready to build a more stable governing pact with the Conservatives, Socialists, Communists, and Greens. Unlike in June, after the parliamentary election, all these parties seem ready to make compromises and avoid another government at the mercy of the far-right National Rally. But that’s only a temporary fix. He still doesn’t have a solution to reverse the surge in popularity far-right Marine Le Pen has enjoyed since 2017, and her significant chances of being elected president in 2027.

With Germany in turmoil for the foreseeable months, and given Trump’s distaste for the EU, Macron has an opportunity to turn France into the facilitator of greater European margins of maneuver.

To pull that off, he will have to pass two simultaneous crucial tests. Domestically, he must make things right by constructively engaging in compromises with conservative and left-wing parties to produce a stable long-lasting government that can turn around the country’s fiscal situation. Internationally, he must build a coalition of strategically minded European countries able to immediately deliver robust security guarantees in Ukraine and weigh on the coming Ukraine negotiations. Fears of escalation should be checked against Russia’s forced retreat in Syria and the loss of its single most important overseas strategic outpost without much of a fight.