Kristi Raik

Director of the International Center for Defense and Security, Tallinn

First, the more Europeans assist Ukraine, the more pressure they generate on Russian President Vladimir Putin to stop fighting—not vice versa. It is Europe’s weakness and hesitation that encourage Russia and allow Putin to believe that he can achieve a better outcome by continuing the war. Europeans must define their long-term commitments so that Russia’s calculation changes and continuation of war no longer pays off.

Second, Russia must not be given veto power over security guarantees provided to Ukraine, including the deployment of a European reassurance force. Europe has the obligation and right to assist Ukraine, a country under unlawful attack, based on Kyiv’s request.

Finally, Europeans should focus on giving to Ukraine the kind of assistance that is most effective in helping the country defend itself. Deployment of some forces before a ceasefire should not be excluded. However, it is not going to be a decisive factor in changing the trajectory of the war. Ukraine’s own defense capability, supported by its allies, is the most critical factor in bringing an end to the war and creating credible deterrence for the future.

Jakub Janda

Director of the European Values Center for Security Policy

Russia’s war against Ukraine is ultimately enabled and boosted by China. Once China decides, it can force Russia to withdraw from Ukraine. Russia and China—like any dictatorships—only react to force. Therefore, after eleven years of Russian war in Europe, Europeans should deploy several divisions of forces to Ukraine right now. This is the only physical move European countries can do to change Russian and Chinese decisionmaking about continuing their joint aggressive war.

The other move European countries should do is to enact EU sectoral sanctions on the main sponsor of this largest European war since 1945: China. Access to the European market is important to the Chinese Communist Party to ensure Beijing’s economic stability. Therefore, this pressure point should be leveraged by European democracies who claim that the survival of Ukraine is the key priority. Sadly, this agenda is the largest failure of EU capitals over recent years: To most European leaders, economic relations with China are much more important than pressing Beijing to end the Russian war in Ukraine.

Minna Ålander

Associate fellow in the Europe Program at Chatham House

If you were looking for a threshold, this is it. The Russian drone incursions into Polish air space call for long overdue measures: shooting down stray drones and missiles whenever they pop up in NATO air space. If these weapons strayed off course and a country needs to take measures to safeguard its citizens, it can hardly count as an escalation. As Russia, on the other hand, keeps deliberately escalating the war, the idea of shooting down drones and missiles even in the Western Ukrainian air space is an entirely reasonable countermeasure.

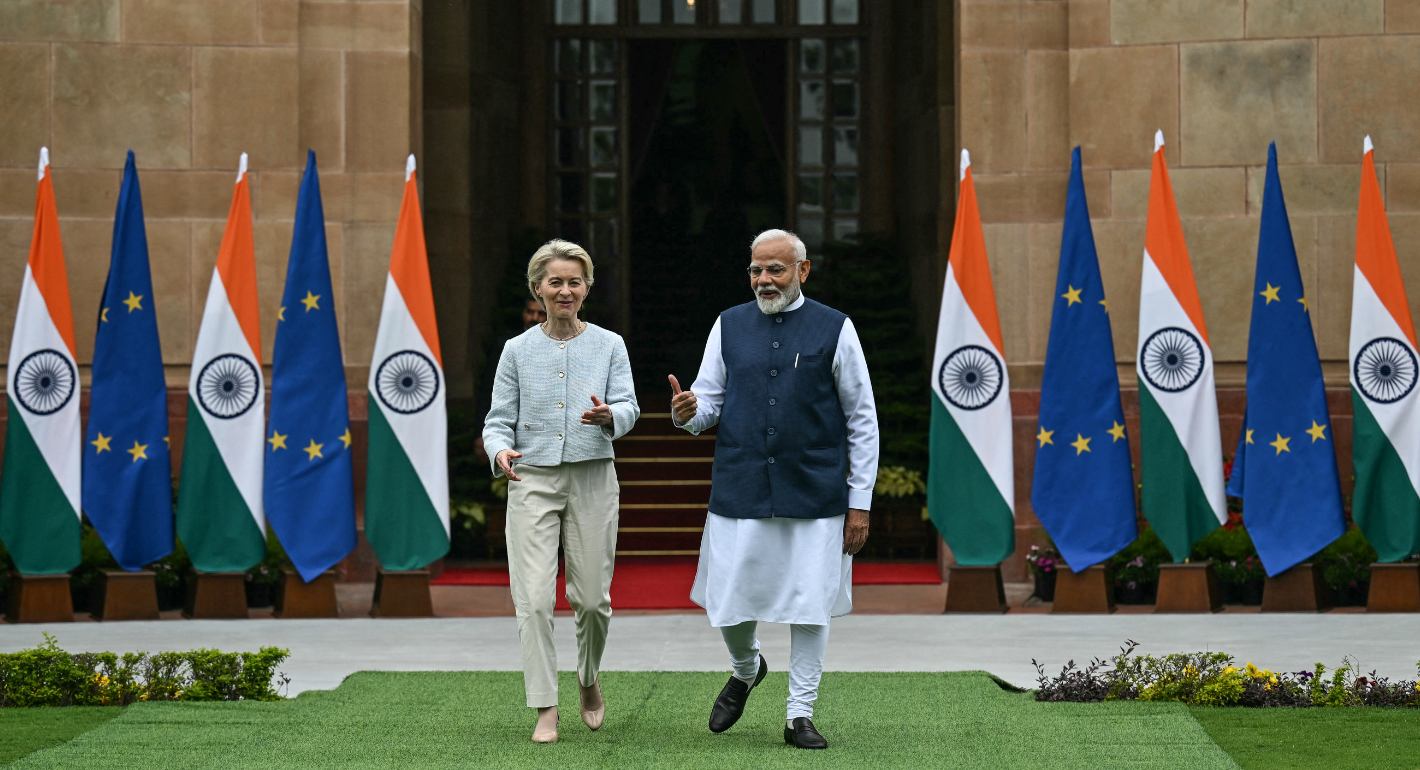

Already the two missiles that missed the EU delegation headquarters in Kyiv by some fifty meters, and the GPS interference of European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen’s plane upon landing in Bulgaria would have warranted a European air defense deployment, at least to Kyiv to secure Europeans operating there. In addition to diplomatic representations, European defense industry sites and joint ventures in Ukraine could be considered for air defense deployments. Waiting for a ceasefire that is clearly not happening anytime soon is disingenuous, and European citizens can see through their leaders’ empty posturing.

Élie Tenenbaum

Director of the Security Studies Center at Institut Français des Relations Internationales (IFRI)

The more the coalition of the willing keeps promising to deploy European troops in the event of a ceasefire, the more it incentivizes Vladimir Putin to never sign any deal that may open the door to such an operation, which ranks high up in his must-avoid list.

But if the Europeans were to act, however symbolically, toward a deployment before a ceasefire, it might reverse the Russian calculation. Enforcing an air defense zone over Western Ukraine with combat air patrols and ground-based air defense to shoot down cruise missiles, and deploying a military training and assistance mission on-site would change facts on the ground, while not directly threatening Russian forces nor amounting to actual belligerence.

Russia would then have to choose between escalating by striking European assets and facing the consequences or suffering the presence of a European force with the risk of a spillover effect. This creates an incentive for Russia to rush toward a ceasefire where it could negotiate the size and scope of a European military presence.

If Europeans are too timid to contemplate such a move, better stop talking about security guarantees and concentrate on what is actually helping: increasing financial aid and military deliveries to Kyiv and bracing for what comes next.

Sophia Besch

Senior fellow in the Europe Program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

Two things can be true. By conditioning deployment of a reassurance force on a ceasefire, Europeans effectively allow Putin to hold any deployment hostage. And sending troops regardless would be ill-conceived.

The reassurance force debate has already done useful work: It forced Europeans to lay their cards on the table, to confront what would actually be required, and to admit to each other who would—or would not—contribute. It also served as a valuable way of signaling to U.S. President Donald Trump that Europeans were serious about Ukraine and expected, if not a seat at the table, then at least a hearing in return.

But what began as a useful political prod risks morphing into a promise of military action that Europe is not ready to deliver on right now. Europeans cannot speak a credible American backstop into existence. Russia would have little difficulty calling a European bluff, and Europeans are not prepared to fight a war with Moscow. Plus, narrowing the discussion over how to support Ukraine to a binary choice over collective military deployment risks distracting from what can already be done today—training, equipping, and helping Kyiv rationalize its forces—and what must still be done in the future.

Marcin Terlikowski

Head of research at the Polish Institute of International Affairs (PISM)

It depends on what type of force. Much too often, the thinking of both political leaders and experts has followed established patterns when it comes to foreign military engagement in Ukraine, being strangled by the very many redlines. Yet, those proved to be more imaginary than real: As of today, the EU helps to equip and train Ukrainian forces, which deploy American medium-range missiles, tanks, and fighters, while being fed by the U.S. reconnaissance data. On September 10, an even more important breakthrough happened: Polish and Dutch air forces, operating under NATO command, shot down Russian drones attacking Poland—a first ever such an encounter in the modern history of Europe.

If the Russian drones attack teaches us anything, it is that any Russian aggression can—and must—be actively fought against. That does not necessarily need to be achieved through ground deployments. The thinking of the coalition of the willing should focus more on the air domains than the land or maritime component of the prepared mission. A large international buffer or separation force to be deployed at the line of contact is neither expected by Ukraine, nor feasible. But a European force intercepting Russian air attacks—which may be threatening neighboring NATO allies—could be a game changer.

Claudia Major

Senior vice president overseeing transatlantic security initiatives at the German Marshall Fund of the United States (GMF)

Europeans need to change Russia’s calculus and make it more attractive to end the war than to continue it. Neither their economic pressure on Russia, nor their military support for Ukraine have achieved that. Europe’s hesitance to impose redlines for Russia—as the drone incident in Poland showed—gives Moscow the impression that it has little to fear.

Alas, the debate about deploying troops before a ceasefire or about security guarantees is largely theoretical. The appropriate units, the political support, and reliable U.S. contributions are lacking. Almost all Europeans won’t move without a U.S. backstop. If Russia were to attack European allies while the United States stood by, NATO’s loss of credibility would be devastating.

Further, Europeans have locked most of their forces into NATO’s defense planning. They would need to reprioritize their plans, thereby consciously weakening the protection of their own territory and taking risks to secure Ukraine, which they are not willing to do.

Eventually, Europeans must credibly convey to Russia and Ukraine that they are now prepared to fight for Ukraine and against Russia. But a bluff and pray approach, based on the hope that Russia will not test the European’s readiness to act, would be reckless and could increase the likelihood of yet another war in Europe.