Judy Dempsey

{

"authors": [

"Judy Dempsey"

],

"type": "commentary",

"centerAffiliationAll": "dc",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"Carnegie Europe"

],

"collections": [

"Europe’s Eastern Neighborhood",

"Ukraine’s Long Shadow"

],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Europe",

"programAffiliation": "EP",

"programs": [

"Europe"

],

"projects": [],

"regions": [

"Russia",

"Europe",

"Eastern Europe",

"Western Europe",

"Germany",

"Iran"

],

"topics": [

"Foreign Policy",

"EU",

"Security",

"Economy",

"Military"

]

}

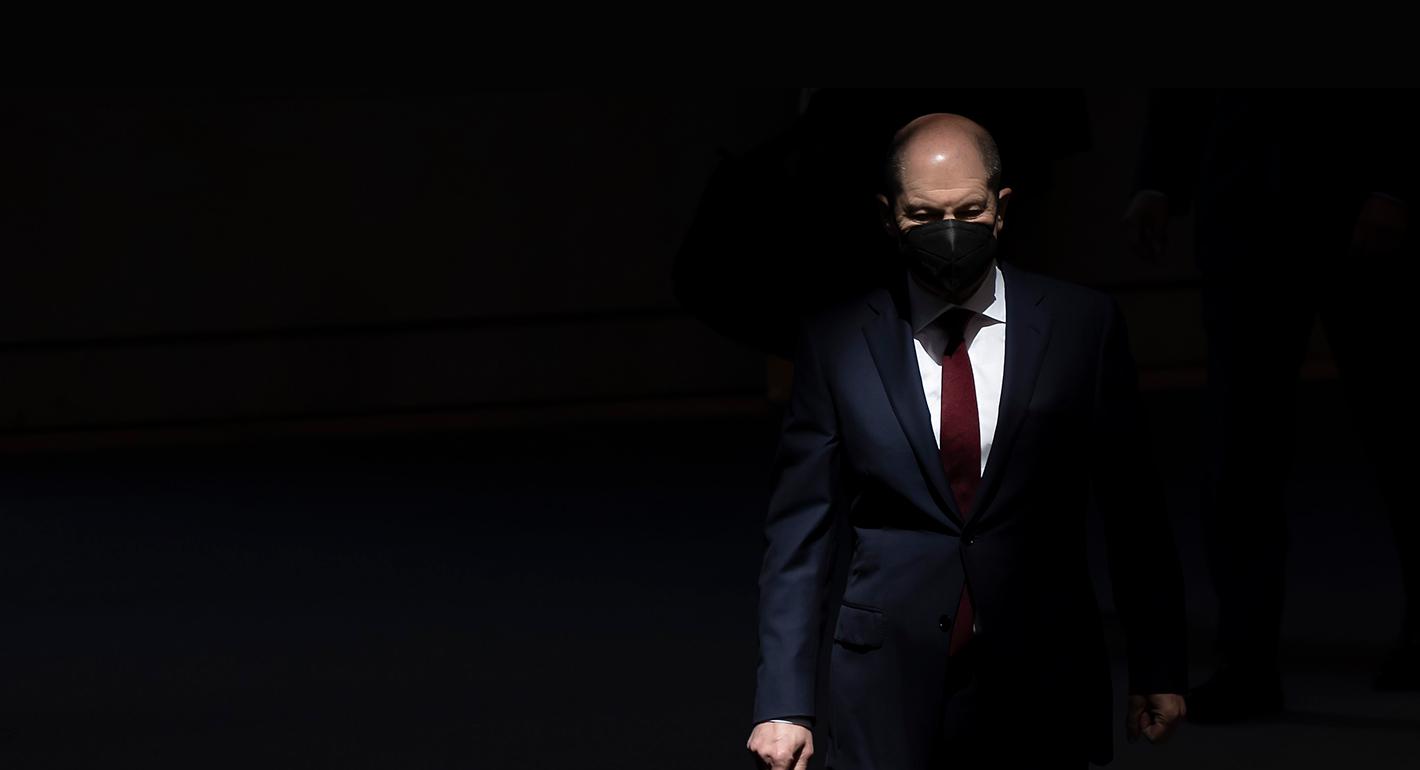

Source: Getty

Russia’s Invasion Has Become a Watershed Moment for Germany

Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s speech to parliament fundamentally shifted Germany’s foreign, security, and defense policies, with major regional repercussions.

In just thirty minutes on Sunday, Chancellor Olaf Scholz put Germany on a radical new path.

In an extraordinary speech made during a special session of the German parliament on Sunday, Scholz ended the decades-long Ostpolitik of his Social Democratic Party (SPD), with immense ramifications for Europe and NATO. Ostpolitik, or “eastern policy,” was forged in the early 1970s and intended to bring the Soviet Union politically and economically closer to Europe. One major component was building a gas pipeline, which the United States opposed, that West Germany hoped would bring confidence, stability, and predictability with the USSR. But Ostpolitik also meant that Germany’s ruling left wing had little sympathy for dissident movements in communist Eastern Europe, as these movements upset the Cold War status quo. That belief in having a special relationship with Russia persisted even when President Vladimir Putin invaded Georgia in 2008 and annexed Crimea in 2014. Germany’s powerful and influential business lobbies and pro-Russia left-wingers preferred to protect their interests with Russia, despite the Kremlin’s crackdown on human rights, press freedom, and civil society.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on Thursday was the last straw for Scholz. He became convinced that Germany could no longer hedge its bets with Russia. In his speech to legislators, he laid out his vision for the country’s radical shift.

Scholz said German defense spending would increase to 2 percent of gross domestic product, meeting the target set in 2014 during NATO’s summit in Wales. In addition, he announced a special 100 billion euro ($113 billion) fund to provide much-needed basic equipment for the German armed forces. Scholz also said Germany would send weapons to Ukraine, ending a long-held policy that it would not deliver weapons to a conflict zone—hardly a plausible argument when Germany supplies weapons to authoritarian regimes. Finally, the country would move quickly to reduce its dependence on oil and gas. This means sharply cutting back its imports of Russian energy, which account for 55 percent of its gas imports.

Apart from mapping out an ambitious new course for Germany, it was Scholz’s impassioned support for Ukraine that won him rapturous applause. “The twenty-fourth of February 2022 marks a watershed in the history of our continent,” he said. “With the attack on Ukraine, Russian President Putin has started a war of aggression in cold blood.”

But what does Scholz’s speech mean in practice?

First, Russia has lost one of its most important supporters in Europe, and Germany no longer sees Armenia, Belarus, Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine through the prism of Russia. The time when the SPD tacitly acknowledged Russia’s sphere of influence over these sovereign, independent countries is over. In addition, Germany’s relations, particularly with Poland and the Baltic states, will markedly improve. These countries were highly critical and distrustful of Berlin’s commitment to Nord Stream 2, the $11 billion project to bring Russian gas directly to Europe that was finished and awaiting certification when Scholz halted it last week. They, along with Ukraine, believed the pipeline would increase their vulnerability in terms of energy supplies and make Germany more dependent on Russia for its energy, pushing Germany to lean more Russia-friendly inside the EU and NATO. Expect a thaw in relations.

Scholz’s announcement to send weapons to Ukraine will also boost Germany’s standing in this part of Europe. Early last month, Germany faced widespread ridicule over its promise to supply Ukraine with 5,000 helmets, as other NATO members sent weapons, and it blocked Estonia’s move to send German-made weapons to Kyiv. This policy change ends the long-held suspicion that Berlin did not want to antagonize Russia.

In addition, these decisions are a boost for NATO, with Germany now fully committed to the defense of Europe via the U.S.-led military alliance. The change shows that Germany no longer wants to be seen as a “free rider,” always relying on the United States to be Europe’s security guarantor without paying much for that security umbrella. Germany was repeatedly criticized for its unwillingness to spend 2 percent of its gross domestic product on defense, and this raised questions among allies if Germany was taking America’s protection for granted.

One caveat to the increase in defense spending. The 100 billion euro “special fund” will kickstart a long overdue modernization of Germany’s armed forces. This is no joke: German soldiers were sent recently to the Baltic states lacking thermal underwear and other basic clothing. But spending more over the next few years will not be useful if it leads to more duplication of equipment among allies instead of focusing on adapting weapons systems to cyber attacks, modern aircraft fighters, and the changing nature of warfare.

Germany could now shape the future direction of EU foreign policy. The war in Ukraine has shown how the EU, pushed by Germany, needs a revamped “Eastern Partnership” policy that entails not only reducing Russian interference, especially by pro-Russian and local oligarchs in politics and the economy, but also strengthening the state institutions and combating corruption. Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine—countries in which Russia has consistently meddled—want to join the EU, or failing that, some special relationship that will make their trade, economy, political, and social structures more closely tied to Europe. Scholz’s policy change indicates that Germany will no longer stand in the way of these changes, and could even lead them.

Former chancellor Angela Merkel never gave a seminal speech about her views on Europe. Scholz, and his pro-EU Green Party foreign minister Annalena Baerbock, now have a chance to make Europe more integrated, especially in foreign policy. Berlin, using its emancipation from Ostpolitik, can now fully join its EU and NATO allies to deal with this unfolding new era. Scholz’s journey has only just begun.

About the Author

Nonresident Senior Fellow, Carnegie Europe

Dempsey is a nonresident senior fellow at Carnegie Europe

- Europe Needs to Hear What America is SayingCommentary

- Babiš’s Victory in Czechia Is Not a Turning Point for European PopulistsCommentary

Judy Dempsey

Recent Work

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

More Work from Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

- Who Will Be Iran’s Next Supreme Leader?Commentary

If the succession process can be carried out as Khamenei intended, it will likely bring a hardliner into power.

Eric Lob

- Turkey Has Two Key Interests in the Iran ConflictCommentary

But to achieve either, it needs to retain Washington’s ear.

Alper Coşkun

- What Is Israel’s Plan in Lebanon?Commentary

At heart, to impose unconditional surrender on Hezbollah and uproot the party among its coreligionists.

Yezid Sayigh

- What Does War in the Middle East Mean for Russia–Iran Ties?Commentary

If the regime in Tehran survives, it could be obliged to hand Moscow significant political influence in exchange for supplies of weapons and humanitarian aid.

Nikita Smagin

- Bombing Campaigns Do Not Bring About Democracy. Nor Does Regime Change Without a Plan.Commentary

Just look at Iraq in 1991.

Marwan Muasher