In the last several years, the European Union (EU) has been understandably preoccupied with Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine and the need to strengthen military defense capabilities. This focus on classical military security may well have been necessary, but has at least partly displaced longer-term and nontraditional security issues from the EU’s external agenda. As the new EU leadership takes office, this trend looks set to extend even further.

Yet, while a tragic war unfolds in Ukraine, other challenges show no sign of abating. Indeed, a more structural, underlying pattern has rooted itself in many of the countries that are high priorities for EU foreign policy: Climate stresses, conflict dynamics, and governance problems have all worsened dramatically in recent years. There is evidence of a fast-accumulating triple nexus between these climate, conflict, and democracy crises.

Current EU policies are not equipped to deal fully with this triple nexus. Changes are needed to improve these policies’ ability to do so, because it will become increasingly suboptimal to address any one of these challenges in isolation from the others. The EU needs ways to integrate its currently disparate climate, conflict, and democracy policies into a seamless whole. This will become an ever more pressing and cross-cutting imperative for EU foreign policy but, at present, risks getting lost from view because of other more tangible, short-term priorities.

The Era of the Three Crises

These are not new policy concerns and the EU has been developing strategies for climate security, conflict, and democratic governance for many years. But it does appear that the mutually reinforcing links between these problems have recently become more unsettling and consequential.

Policymakers and analysts have been charting the relationships between climate change and multiple kinds of political, social, and economic instability for many years. There is a broad consensus that climate change–related effects increase countries’ propensity to conflict and political turbulence, particularly where instability is already present.1 It is equally well established that with so many complex factors at play, there is not usually a direct causal connection between climate change and conflict, and that climate stresses manifest themselves mainly indirectly through many intermediate factors and dynamics. Still, these broader knock-on effects from climate change have clearly accelerated and intensified in the last several years.

While this picture of the general links between different crises has been basic knowledge for some time, current trends are generating heightened concerns. A 2023 report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) noted the current expansion in “humanitarian crises where climate hazards interact with high vulnerability.”2 The IPCC has stressed that deficits in socioeconomic development and political rights are increasingly acting together in sharpening conflict vulnerabilities.3

As climate change impacts become more dramatic and tangible, conflict dynamics have deepened, too. According to the 2024 Global Peace Index of the Institute for Economics & Peace, the world is now facing the highest number of conflicts—fifty-six—since World War II.4 In 2023, the number of internally displaced people reached a record high of 75.9 million, with a striking overlap between displacement and climate change–related disasters: Of forty-five countries and territories that experienced internal migration due to conflict, only three did not report disaster-related displacement.5 Prominent experts insist that upgraded environmental peacebuilding is now urgently needed to address specific climate change–related concerns in fragile contexts.6

Meanwhile, an equally worrying democracy crisis has unfolded in parallel with the climate crisis. In formal summits and processes, the need for more democratic engagement on the climate emergency has become increasingly urgent. The December 2023 United Nations (UN) Climate Change Conference (COP28) called for more “gender-responsive, participatory and fully transparent” approaches to climate action.7 At the summit, governments agreed on a Just Transition Work Program that promises more inclusive and participatory approaches to the climate transition.8

Nondemocracies and conflict-affected or fragile countries tend to rank low in Yale University’s 2024 Environmental Performance Index.9 Many of the states that have registered the most severe democratic regressions in recent years are those that suffer conflicts and climate change vulnerabilities. The 2023 progress report of the UN’s Climate Security Mechanism stressed that “of the 30 countries most vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, 18 are experiencing conflict or fragility and 13 also rank among the 30 countries with the lowest women’s inclusion, justice, and security scores.”10 Against this backdrop, many campaigns are gaining support for the climate crisis to be understood and tackled as a governance crisis that requires deep institutional change.11 A coalition of rights organizations has urged the International Criminal Court to address atrocities that result from climate vulnerabilities.12

EU foreign and security policies have not evolved fully to reflect these mounting concerns. In principle, the union has long recognized the need to fuse its conflict and climate policies under the rubric of its climate security strategy, which it first developed in the early 2010s. Yet, this agenda has never been an especially high priority, and EU climate security has left little identifiable mark on the countries where the union is active.

After the Russian invasion of Ukraine, European powers and the EU collectively upgraded their commitments to address the geopolitical dimensions of climate change as part of the spillover effects of the attack. The war has “made decarbonization a strategic imperative” for the bloc, according to two senior EU figures.13 In June 2023, the EU agreed on an upgraded climate security strategy that recognized the need to move this area of policy toward more tangible action.14 However, the war on Ukraine has required the EU to focus on traditional imperatives of territorial security that now appear far more concrete and urgent than the long-term and less dramatic challenge of climate security.

The EU’s updated climate security strategy focuses mainly on streamlining internal decisionmaking processes, undertaking more studies and ecological assessments, and offering diplomats more training on environmental issues; it does not come with new funds and does not appear to have led to concrete policy changes in particular countries. The EU has moved to include environmental advisers and focal points in its Common Security and Defense Policy (CSDP) missions and operations.15 And in 2022, the bloc drew up guidelines for including climate issues into civilian CSDP missions.16 Still, the union has not actually deployed any missions to deal with conflicts related to climate change.

The EU Political Guidelines presented by European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen for 2024–2029 acknowledge climate change as a priority, but they focus on climate neutrality and decarbonization, with no mention of external dimensions of the climate emergency.17 The EU’s new leadership has committed mainly to reinforced energy diplomacy in a way that is rather separate from the dynamics of the three crises. The mission statements given to the new team of European commissioners contain little that is relevant to the challenges outlined in this paper but instead foreground traditional security and external economic interests.18

The Triple Nexus: The Evidence

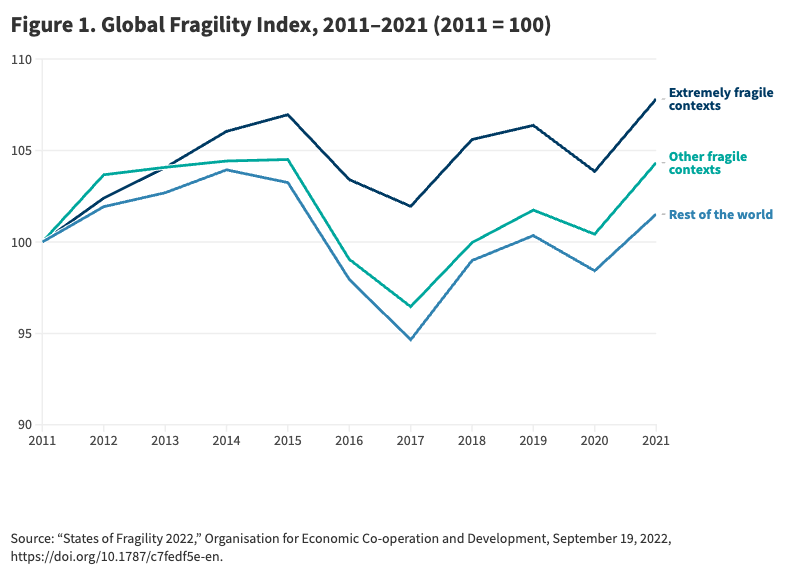

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s (OECD’s) “States of Fragility 2022” report highlighted that the world is navigating through an “age of crises,” with the COVID-19 pandemic, climate change, and conflicts increasingly entwined with each other.19 The report identified sixty fragile contexts that are home to 23 percent of the global population and 73 percent of the world’s extreme poor; in these areas, 1.9 billion people face severe humanitarian needs. Overall, fragility has steadily worsened around the world since 2011 (see figure 1).

Crucially, the three crises—conflict, climate change, and governance—are converging in many countries. The number of states that suffer elements of all three crises has increased dramatically in the last decade.

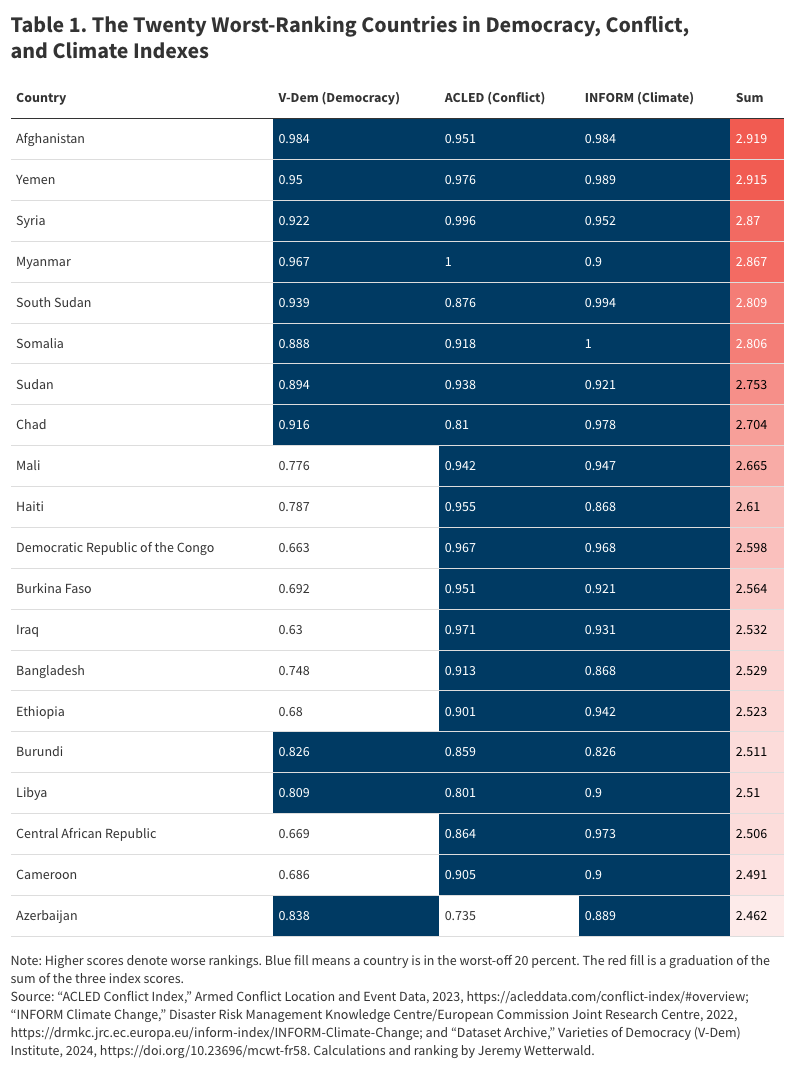

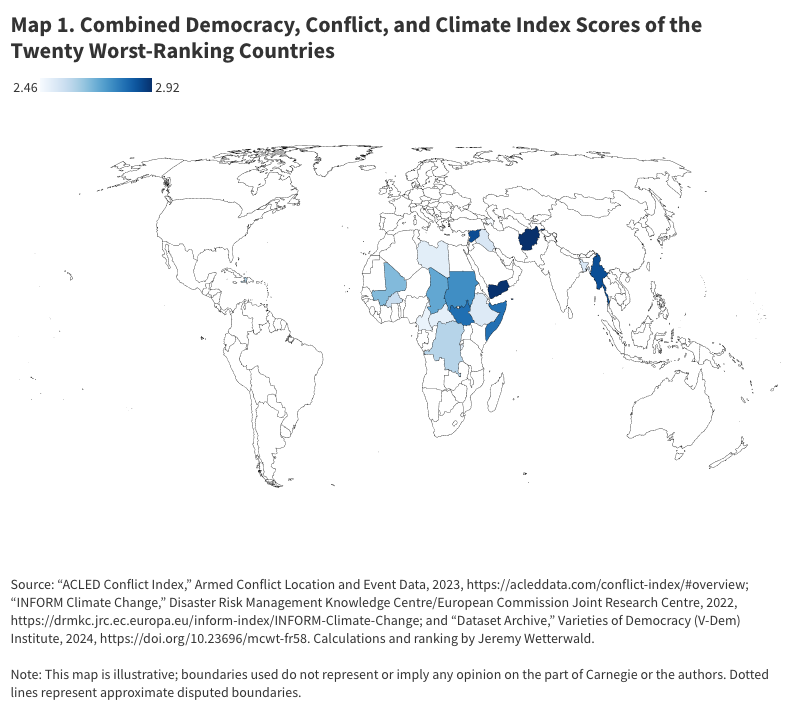

In addition to the increased spread of fragility in general, the three dimensions of fragility related to climate change, governance, and conflict in particular are converging geographically. In the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Institute’s democracy indexes, the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data (ACLED) Conflict Index, and the INFORM Climate Change Risk Index of the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre, fragile countries systematically ranked among the worst off across the board (see table 1 and map 1).

This geographic convergence and concentration of crises in fragile countries manifests itself at the humanitarian level. According to data from the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) Financial Tracking Service, the twenty worst-ranking countries in terms of climate vulnerability, conflict, and democracy also register the highest—and rising—levels of humanitarian financial needs (see table 2).

Country and Regional Examples

Several examples help show in more granular detail how the climate, conflict, and governance crises are converging and leading to systemic regional destabilization. Three case studies stand out: the Sahel and the Lake Chad region, Syria, and Afghanistan.

The Sahel and the Lake Chad Region

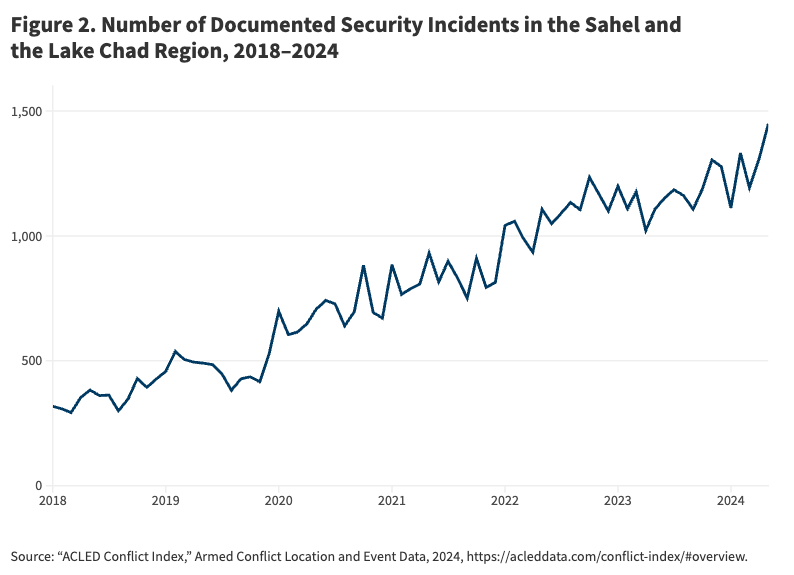

The Sahel is grappling with major compound crises that have been escalating since 2011. Climate change and socioeconomic drivers are leading to conflicts over land use, which are negatively affecting rural livelihoods and generating intergroup tensions. In turn, fragility and conflict have amplified grievances against national governments and increases in violence and extremism across the region, with a fourfold rise in documented security incidents between 2018 and 2024 (see figure 2).

The region’s multifaceted crises have resulted in significant humanitarian impacts and deeply unsettling changes to political regimes. The UN estimates that in 2024, more than 32 million people in the Sahel require humanitarian assistance.20 More than 7 million people have been displaced either within national borders or to other countries, and there are no signs of an improvement to the crisis.21 Food insecurity is a major issue, and conflict-affected areas are systematically classified as suffering from a food security crisis.22

All countries in the Sahel are highly or very highly exposed to climate change risks.23 In 2024, the region was affected by a heat wave driven by climate change, exacerbating a context of extreme poverty, conflict, and unprecedented humanitarian needs.24 Over the last ten years, the central Sahel and the countries around Lake Chad have experienced at least 780 disasters.25 The UN’s 2023–2024 human development report showed that with the exception of Cameroon, the Sahelian countries fall below the low human development threshold.26 Some 38 percent of the region’s population—roughly 125 million people—live on less than $1.90 a day.27

Meanwhile, competition over land and water resources between farmers and herders has heightened tensions across the region.28 Driven by increased variation in temperatures and precipitation as well as rapid demographic changes, scarcities of land and water resources are putting pressures on livelihoods. These pressures on the well-being of mostly rural and economically deprived communities then generate grievances against institutions, increasing political fragility.

Alongside these climate and conflict stresses, the region has suffered major democratic regression and a cluster of military coups in recent years. Since the 2020 Malian coup, there have been ten further overthrows or coup attempts across Central and West Africa. Military takeovers have been successful in Burkina Faso, Guinea, and Niger as well as nearby Gabon and Sudan, and promises to go back to civilian rule have been delayed. In Chad, President Mahamat Déby took power in 2021 after the death of his father, tightening autocracy.

Against the backdrop of this wave of coups, the Sahel now accounts for more than half of all deaths related to violent extremism across Africa.29 Democracy indexes rank the region as one of the most autocratic in the world, signifying a democracy crisis that is clearly deepening in parallel with conflict and climate stresses. Security spending has increased in countries such as Burkina Faso and Mali, potentially drawing funds away from governance capacity in other areas, like climate change mitigation and conflict prevention.30

Syria

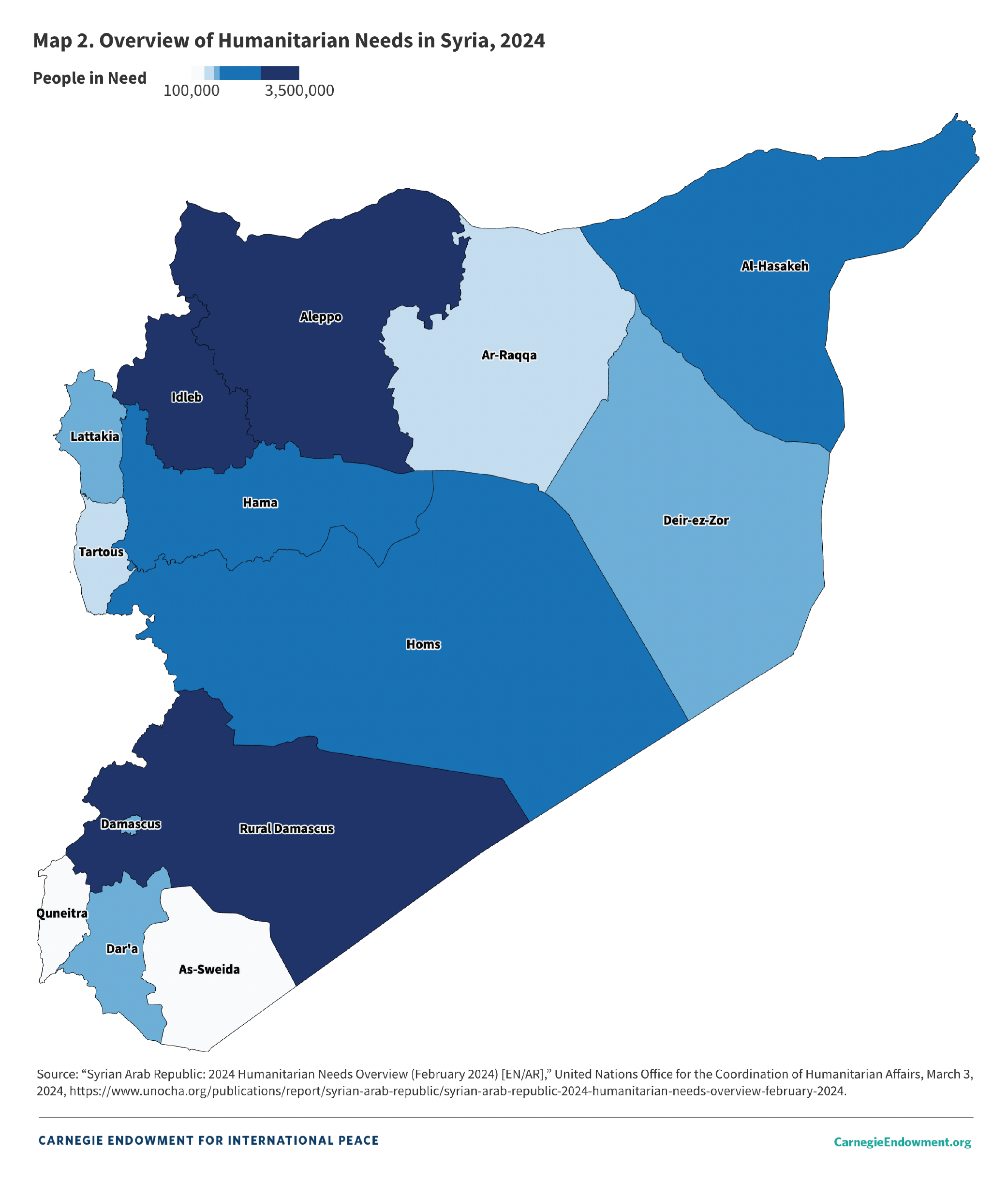

In Syria, a combination of socioeconomic, political, and environmental factors contributed to one of the world’s longest crises in the 2010s. In 2024, Syria still faces a complex situation characterized by persistent conflict, a brutally repressive autocracy, and mass-casualty disasters that are both related and unrelated to climate change. The country registers some of the highest levels of humanitarian need (see map 2).31

OCHA’s February 2024 humanitarian needs overview reported that an estimated 16.7 million people required assistance, with most of the needs concentrated in regions that experience multiple simultaneous shocks, such as earthquakes, authorities’ inability to provide basic services, and conflict.32 Syria has one of the highest rates of water scarcity globally and is experiencing severe drought.33 Water scarcity, coupled with higher temperatures, is increasing pressure on land resources, causing severe strains on agricultural production and food security. The UN activated a water crisis response plan for the country in 2022. This was on top of the UN’s humanitarian response plan, highlighting the humanitarian system’s inability to deal with overlapping shocks.34

In parallel with the war and climate stresses, authoritarianism has deepened. Syria’s government is now more repressively autocratic than it was before the war began in 2011. The country ranked 163 out of 167 states on the Economist Intelligence Unit’s (EIU’s) 2023 Democracy Index, and its democracy score stood at a lowly 1.43, compared with 2.31 in 2010.35 Syria’s July 2024 parliamentary election was entirely manipulated to ensure a false illusion of legitimacy.36 In May, the UN’s special envoy for Syria reported ongoing violence in the country and an absence of political progress.37

Afghanistan

Over the past decade, Afghanistan has suffered one of the world’s most high-profile set of crises, exacerbated by political instability, economic decline, and disasters. The UN estimates that as of 2024, over half of the country’s population requires humanitarian assistance.38 The compound crises are intensified by international sanctions and the suspension of foreign aid, with severe food insecurity now affecting millions.

Since the Taliban takeover in August 2021, Afghanistan’s gross domestic product has dropped by 25 percent and its unemployment rate has risen sharply, particularly among women.39 As a result, roughly 85 percent of Afghans live on less than $1 a day.40 The underlying shocks that drove these needs include the Afghanistan-Pakistan border crisis, which pushed 1.3 million undocumented Afghans from Pakistan into the country;41 three years of weather conditions disrupted by La Niña, which generated more frequent and severe droughts and floods; and the 2023 earthquakes near the western city of Harat.42 In an October 2023 humanitarian needs assessment by the REACH initiative, households across the country reported exposure to shocks in the previous three months.43

As in the previous cases, the linkages between climate change, conflict, and governance trends have become more tightly interwoven in recent years. Climate change–driven increases in the frequency and severity of extreme weather events are intensifying environmental stresses and leading to greater scarcity of natural resources, especially water and land. This, in turn, has impeded access to resources and affected livelihoods and food security.

In parallel, Afghanistan has suffered long-running instability and bouts of open conflict. The 2021 Taliban takeover dramatically interrupted the country’s tentative and faltering efforts at democratization. The EIU’s 2023 Democracy Index ranked Afghanistan as the world’s most autocratic country.44 While internal violence and autocratization stem from many factors and have complex roots, it is striking how some of the worst trends in conflict, environmental degradation, and repressive governance coincide in the same place. Afghanistan is one of the starkest examples of how the lack of an inclusive governance system and weak rule of law have contributed to greater political and economic inequality, as conflict and local competition for natural resources aggravate the problems experienced by marginalized social groups.45

Cross-Cutting Patterns

These three regional and national case studies showcase the conceptual model that plots linkages between climate change, fragility and conflict risks, and crises of political governance. Even if there are many drivers of fragility, climate change’s often-mentioned influence as a risk multiplier has clearly intensified in the last several years. In the Sahel and the Lake Chad region, Syria, and Afghanistan, climate change is generating more frequent extreme weather events, including precipitation and temperature anomalies. This trend is driving environmental changes in the availability of natural resources, affecting livelihoods and generating grievances among affected communities. Autocratization feeds into, flows from, and exacerbates these climate stresses and ongoing conflict dynamics.

The question of causality in this triple nexus is a difficult one. For two decades or more, academics have debated this question and generally cautioned against overly bold claims about direct causal links between climate change, conflict, and governance crises—even as they stress the deepening interrelationships between them. This is a complex area of debate that lies beyond this paper. What this analysis shows is that the three crises increasingly converge at the country level and that in the real world of international policy, they therefore need to be tackled in conjunction. Given the complexities and nuances in transmission between the three crises, it seems increasingly suboptimal for international actors to develop largely separate strategies for each.

Donor Responses

The EU has dedicated diplomatic efforts and resources to the countries suffering from the triple nexus of crises. However, the union’s interventions are rarely directed at the coexistence of the three crises or the overlaps between them. There is little evidence of European donors pursuing a single, integrated, and comprehensive strategy for the triple nexus. Many of the states identified above receive large amounts of EU aid, yet little of this aid is directed at the confluences between the three crises. The EU certainly invests large amounts of funding into climate transition projects around the world, but these are directed only to a modest extent toward the governance- and conflict-related root causes of fragility.

Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the EU has plowed increased funds into multiple new external agreements that enshrine upgraded cooperation with third countries on renewable energy. Together, the EU and its member states are the largest source of climate finance in the world—nearly €30 billion ($32 billion) a year—and have promised to double adaptation funding during the 2020s.46 European states and the EU have supported the Group of Seven (G7) Just Energy Transition Partnerships with India, Indonesia, Senegal, and Vietnam. The EU’s €1 billion ($1.1 billion) contribution to the €20 billion ($21 billion) partnership with Indonesia was the union’s biggest-ever climate funding initiative.47

Meanwhile, the EU’s Global Gateway infrastructure financing initiative includes a swath of new projects related to energy transitions in developing states. EU countries have been among the first to put funds into the new loss-and-damage fund approved at COP28 to help tackle developing countries’ climate change–related challenges and have supported a new fund for victims of climate disasters.

Yet, the states suffering most glaringly and acutely from the triple nexus seem to have fallen down the EU’s list of priorities. More EU funding is directed now than previously at exporting renewable energy to European markets in a way that risks accentuating local conflict dynamics. The same risk is evident in the EU’s push to expand environmentally harmful critical-mineral mining in developing countries to meet the bloc’s needs for supplies. New EU green hydrogen projects are oriented primarily toward solving the European energy squeeze and could be detrimental to local stability.48 The EU’s upgraded climate agreements increase aid for renewables, but they are not set up to address the social tensions and instability associated with global energy politics in the longer term.

The EU has introduced some climate change adaptation funding into its migration control aid and its conflict programs in selected countries, but it has not made climate action the central pillar of its security policy. The EU now has very limited CSDP presence in the states where the evidence shows acute impacts of the triple nexus. There is no EU strategy for mitigating territorial fragmentation in conflict states or the ways in which climate and governance strains can exacerbate this fragmentation.

And on the governance strand of the triple nexus, EU democracy assistance has begun to include a focus on climate change–related activism but still unfolds on a largely separate policy track. The union is yet to develop climate and governance criteria in the evaluation and monitoring benchmarks for its conflict resolution projects. The EU’s Court of Auditors has criticized the limited funding for rights and governance issues under the Emergency Trust Fund for Africa, which was set up in 2015 as a primary funding vehicle for North Africa, the Sahel, the Lake Chad region, and the Horn of Africa.49

The almost 225 flagship projects rolled out to date under the Global Gateway are not strongly geared toward states affected by the triple nexus.50 As set up at present, the Global Gateway is oriented more to creating commercial opportunities for European companies to invest in infrastructure building than to addressing the combination of climate, conflict, and democracy challenges. The growth of the European Peace Facility—an EU financing instrument aimed at conflict prevention—and its move into providing weapons has been widely celebrated as a notable development in EU foreign and security policy. But again, the facility is quite divorced from the triple-nexus challenge. Several EU member states, such as Denmark and the Netherlands, have conflict prevention initiatives that include links to climate change, or climate funds that foster local inclusion; but triple linkages that address conflict, climate change, and democracy in a fully holistic way do not feature in member states’ aid profiles.

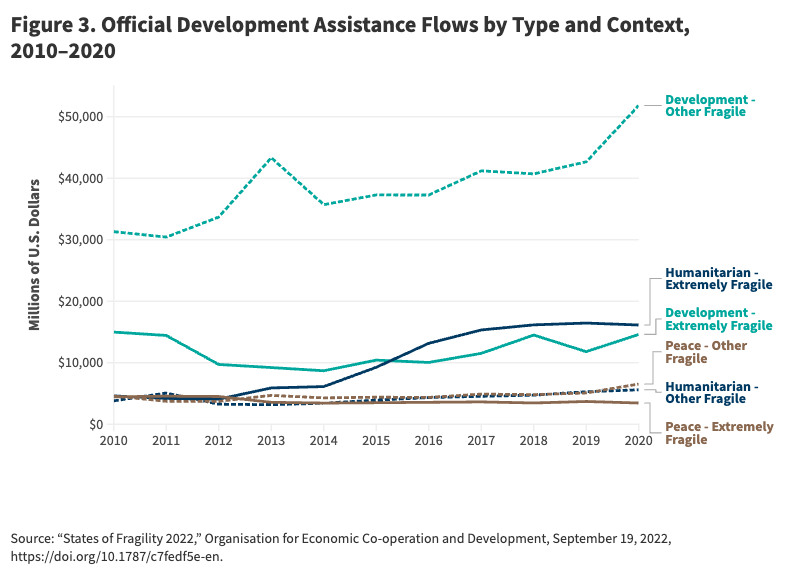

In the last decade, humanitarian assistance in extremely fragile contexts has overtaken standard development assistance as the main mechanism for delivering funds to fragile countries (see figure 3). While the provision of life-saving needs after crises is of course essential, the turn to humanitarian aid has diverted funds from programs and solutions that go beyond addressing basic needs to tackle the underlying drivers of vulnerability. Humanitarian aid was designed for short-term relief but has gradually become the main element of basic funding for extremely fragile contexts over a long period of time. The concept of humanitarian-plus aid, which expands traditional emergency relief into funding that moves toward longer-term recovery, is now a cornerstone of donor approaches.

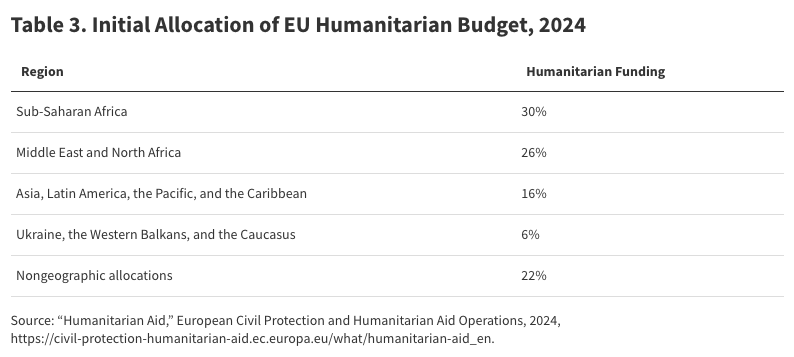

The European Humanitarian Forum, a European Commission initiative that brings together the humanitarian community to explore solutions to help those in need, resulted in pledges of €8.4 billion ($9 billion) in 2023 and €7.7 billion ($8.3 billion) in 2024.51 This year, the EU allocated €1.8 billion ($1.9 billion) for humanitarian aid (see table 3).52

In a global context in which the frequency and severity of climate change– and conflict-driven crises are increasing across the globe but disproportionately affect extremely fragile contexts because of their higher levels of vulnerability, it is critical to think beyond immediate crisis responses. The EU commits to using humanitarian aid to cover “forced displacements, food insecurity, acute and chronic malnutrition, natural hazards and recurrent epidemics . . . which are fuelled by conflict, insecurity and climate change.”53 And with respect to conflict, donors have formally adopted an integrated humanitarian-development-peace (HDP) nexus.54

Yet, a 2024 OECD report found that conflict prevention remains underprioritized and that policymakers often revert to standard humanitarian assistance when it comes to crisis management.55 Donors have not increased resources for countries facing challenges related to climate change, governance, and conflict, and the delivery of nonofficial development assistance to these contexts remains difficult because of governance, corruption, and security risks. Although humanitarian assistance to extremely fragile contexts has increased since 2014, peace funding has not. The EU is set to cut its development spending in 2025–2027, particularly in the world’s least developed nations.56 The apolitical nature of humanitarian funding has increasingly taken precedence over peacebuilding and development efforts in countries with degrading governance and human rights records.

In terms of climate finance, the OECD has noted that conflict and climate aid also seem to be drifting apart and that “the more fragile a country, the less climate-related development finance it receives.”57 A 2023 OECD report showed that on average, extremely fragile contexts receive about one-third of the per capita multilateral climate change–related development finance given to other developing countries.58 As emergency relief has become the primary solidarity mechanism for extremely fragile contexts, OCHA has warned that humanitarian support has become overloaded and that “there is no humanitarian solution to the climate crisis.”59 This situation highlights the importance of improving financing approaches that go beyond humanitarian responses to address multifaceted crises.

While humanitarian relief has increased, it remains well below requirements and struggles to meet the ever-greater needs from overlapping shocks. In 2023, the global humanitarian appeal of $57 billion mobilized only $35 billion in funding.60 Although humanitarian funding tends to increase in major global crises, democracy funding is not as responsive to such events. EU democracy aid has plateaued at modest levels. In one example, the EU and the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) agreed in October 2023 on a package worth €212.5 million ($228 million) for West African countries affected by the triple nexus. Yet, the package had a strong focus on migration and trade competitiveness and lacks funds for democracy assistance.61

In another example, outgoing EU foreign policy chief Josep Borrell acknowledged that in the Sahel, the union had “failed” to strengthen democracy and had excluded local civil society organizations from funding mechanisms.62 While the EU was ostensibly guided by what it termed an integrated approach to the Sahel, donors’ aid programs have neglected local democratic mechanisms for building resilience to climate change.63

In sum, despite much EU rhetoric about crises being inseparable from each other, there appears to be little integrated triple-nexus funding in practice. Climate aid includes relatively little for conflict or democracy; conflict aid does little on climate change or democracy; and democracy aid remains quite marginal to climate change and conflict challenges. While the triple nexus hits increasingly hard in a dozen extremely fragile contexts, EU instruments in these contexts have focused on responding to the consequences and not the root causes of fragility.

Toward an EU Strategy for the Triple Nexus

The evidence shows a tightening relationship between three drivers of crisis in the modern era: climate change, conflict, and limits in democratic governance. Even if causal links cannot be shown with certainty, the three crises are increasingly feeding each other. And yet, EU policy has not incorporated this era-defining trend into its external actions. In part, this is a political choice, as the union prefers to prioritize some pieces of the policy puzzle over others: Climate cooperation is easier if sensitive governance issues are left off the table, for example. But the omission also partly reflects a lack of political consensus behind this trend’s defining importance, affecting the policy instruments and mechanisms that are deployed to implement a triple-nexus approach.

The EU should therefore reconfigure vital areas of its external support to reflect the interplay between the three crises and the need to work on conflict, democracy, and climate change as a single, seamless whole. The EU could do this through changes on three levels.

First, the EU needs to develop a wider and more holistic approach to risk management. The concept of risk-informed, climate change–resilient development has been part of disaster risk management and climate research for many years but often fails to materialize at the country level because of the inherent difficulty of mobilizing action on issues that have not yet manifested themselves in the open. While the availability of evidence to understand both natural and anthropogenic risks has rapidly increased over the last ten years, the use of such evidence to inform decisionmaking and resource allocation remains patchy at best. Siloed approaches to risk management on the three sides of the HDP triangle fail to capture triple-nexus interlinkages.

The EU’s Joint Research Centre has developed a variety of tools to understand a set of identified risks that are updated periodically, usually every year. This approach provides a useful policy tool kit to monitor evolving risks and prioritize them based on evidence. However, the global and annual nature of this assessment does not incorporate rapidly developing political risks. The EU has devised a Global Conflict Risk Index, but this does not speak to the triple-nexus issues outlined in this paper.64 Efforts to better predict and model conflict risks are ongoing but are still too variable to guide the allocation of resources.

The EU needs to better link its various early-warning indicators to combine the three crises as parts of a unified whole. At present, there remains a discrepancy between the ways in which climate stresses drive violent conflict, on the one hand, and the climate indicators used in early-warning assessments, on the other.65 EU early-warning systems remain fragmented as they consider conflict drivers, climate stresses, and democracy issues largely in isolation from each other. The EU needs a unified triple-nexus mechanism to track the three fused crises, none of which can be understood or tackled separately from the others.

Second, the EU needs to better integrate the national implementation of its support for fragile and conflict-affected contexts. Siloed approaches to HDP financing diminish the coherence of EU cooperation at the country level, as the union’s development, humanitarian, and governance partners struggle to jointly address root causes of fragility and vulnerability. Collaboration remains modest in areas where joint approaches are feasible, for example on climate change adaptation and resilience. Better integration would capitalize on the OECD’s 2024 recommendations on the HDP nexus.66

To this end, the EU’s climate security strategy should incorporate a strand of work on the triple nexus to explore these linkages and launch new projects that specifically aim to combine the three areas of challenge. EU humanitarian aid must adapt to protracted crises to ensure that it addresses lasting humanitarian needs while reducing underlying risks as part of a long-term strategy. In multiple contexts, the EU is financing multipartner humanitarian assistance programs with the same partners over many years but still requires yearly planning and reporting. In parallel, the EU needs to tilt its climate funding more toward adaptation—and, indeed, toward a wider notion of adaptation plus that helps local communities adjust to climate change, drivers of conflict, and governance challenges together.

The EU also needs to focus these initiatives more at the regional level, as climate and political dynamics have spillover effects among countries such as those in the Sahel and the Lake Chad region. Such efforts have emerged in these regions through the UN Development Programme’s Regional Stabilization Facility, which brings together several donors, including the EU and some member states, with a focus on security, livelihoods, and social services. This type of integrated approach provides interesting learning opportunities to address drivers of instability across countries and with multiple partners. Although the core objectives of climate action, peace, and humanitarian aid sometimes diverge because of their inherent imperatives, common objectives can often be found at the local level.

Such approaches need to become the norm in EU external action. Where linkages between crises have found a place in concrete EU programs, they still tend to be relatively limited and partial. The long-standing peace nexus builds on mediation, development, and humanitarian needs, while some donors’ conflict funding has begun to support some climate change–related initiatives. Yet, a systematic connection between the three legs of the triple nexus is still absent. The political-governance dimension is especially weak in the large amounts of EU crisis-related humanitarian aid, peace mediation, and climate engagement.

Finally, the EU should build greater cooperation with the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) on the triple nexus. In the last several years, NATO has begun to engage more on both climate change and democracy. The alliance’s 2022 Strategic Concept defined climate change as a “defining challenge of our time,” and in 2023 NATO opened a Centre of Excellence for Climate Change and Security.67 The organization has tentatively moved to work on the linkages between democracy and security, prompted especially by the Russian invasion of Ukraine. As the EU searches for a new relationship with a revived NATO, the triple nexus offers a clear area of opportunity for joint and innovative cooperation on what is set to be an increasingly preeminent strategic challenge.

About the Authors

Richard Youngs is a senior fellow in the Democracy, Conflict, and Governance Program, based at Carnegie Europe.

Ricardo Farinha is a program manager at Carnegie Europe.

Jasper Linke is an assessment specialist in the migration and displacement program at IMPACT Initiatives.

Jeremy Wetterwald is a senior advisor on climate, environment, and migration at IMPACT Initiatives.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Olivia Lazard for her comments on a draft version of this paper.

Carnegie Europe is grateful to the Open Society Foundations for their support of this work.

Notes

1For example, Laura Jaramillo et al., “Climate Challenges in Fragile and Conflict-Affected States,” International Monetary Fund, August 30, 2023, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/staff-climate-notes/Issues/2023/08/24/Climate-Challenges-in-Fragile-and-Conflict-Affected-States-537797.

2“AR6 Synthesis Report: Climate Change 2023,” Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 2023, 35–115, https://doi.org/10.59327/IPCC/AR6-9789291691647.

3Guéladio Cissé et al., “Health, Wellbeing and the Changing Structure of Communities,” in Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2023), https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009325844.009.

4“Global Peace Index 2024,” Institute for Economics & Peace, June 2024, https://www.economicsandpeace.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/GPI-2024-web.pdf.

5“Global Report on Internal Displacement,” Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre and Norwegian Refugee Council, 2024, https://api.internal-displacement.org/sites/default/files/publications/documents/IDMC-GRID-2024-Global-Report-on-Internal-Displacement.pdf.

6Andrew Gilmour, “Climate Change and Conflict Must Be Tackled Together, Argues a Foundation Head,” Economist, April 5, 2024, https://www.economist.com/by-invitation/2024/04/05/climate-change-and-conflict-must-be-tackled-together-argues-a-foundation-head.

7“Conference of the Parties Serving as the Meeting of the Parties to the Paris Agreement,” United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, December 13, 2023, https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/cma2023_L17_adv.pdf.

8“COP28: Overall Outcome & EU Reactions,” European Commission, January 24, 2024, https://ec.europa.eu/social/main.jsp?langId=en&catId=89&furtherNews=yes&newsId=10741.

9“2024 Environmental Performance Index,” Yale Center for Environmental Law & Policy, 2024, https://epi.yale.edu/.

10“2023 Progress Report: Bridging Climate Action, Peace and Security,” United Nations Climate Security Mechanism, May 2024, https://mptf.undp.org/sites/default/files/documents/2024-08/csm_2023_progress_report.pdf.

11Alina Averchenkova et al., “Addressing the Climate and Environmental Crises Through Better Governance: The Environmental Democracy Approach in Development Co-Operation,” Westminster Foundation for Democracy, March 29, 2022, https://www.wfd.org/what-we-do/resources/addressing-climate-and-environmental-crises-through-better-governance.

12Katie Surma, “How Climate Change Drives Conflict and War Crimes Around the Globe,” Inside Climate News, October 26, 2023, https://insideclimatenews.org/news/26102023/how-climate-change-drives-conflict-and-war-crimes-around-the-globe/.

13Josep Borrell and Werner Hoyer, “Decarbonization, a Strategic Imperative,” European Investment Bank, April 29, 2022, https://www.eib.org/en/stories/decarbonization-a-strategic-imperative.

14“EU Proposes Comprehensive New Outlook on Threats of Climate Change and Environmental Degradation on Peace, Security and Defence,” European Commission, June 28, 2023, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_23_3492.

15“1st Joint Seminar for Environmental Advisors and Focal Points in CSDP Missions and Operations,” European External Action Service, December 18, 2023, https://www.eeas.europa.eu/eeas/1st-joint-seminar-environmental-advisors-and-focal-points-csdp-missions-and-operations_en.

16“Operational Guidelines for Integrating Environmental and Climate Aspects Into Civilian CSDP Missions,” European Centre of Excellence for Civilian Crisis Management, 2022, https://www.coe-civ.eu/kh/operational-guidelines-for-integrating-environmental-and-climate-aspects-into-civilian-csdp-missions.

17Ursula von der Leyen, “Europe’s Choice: Political Guidelines for the Next European Commission 2024–2029,” European Commission, July 18, 2024, https://commission.europa.eu/document/download/e6cd4328-673c-4e7a-8683-f63ffb2cf648_en?filename=Political%20Guidelines%202024-2029_EN.pdf.

18For example, Ursula von der Leyen, “Mission Letter: Jozef Síkela, Commissioner-Designate for International Partnerships,” European Commission, September 17, 2024, https://commission.europa.eu/document/download/6ead2cb7-41e2-454e-b7c8-5ab3707d07dd_en?filename=Mission%20letter%20-%20SIKELA.pdf.

19“States of Fragility 2022,” Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, September 19, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1787/c7fedf5e-en.

20“2024 Sahel Humanitarian Needs & Requirements: Overview,” United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), June 2024, https://www.unocha.org/publications/report/burkina-faso/2024-sahel-humanitarian-needs-and-requirements-overview.

21“Sahel Humanitarian Needs,” OCHA.

22“IPC Mapping Tool,” Integrated Food Security Phase Classification, 2024, https://www.ipcinfo.org/ipc-country-analysis/ipc-mapping-tool/.

23“INFORM Climate Change,” European Commission, 2024, https://drmkc.jrc.ec.europa.eu/inform-index/INFORM-Climate-Change.

24“Extreme Sahel Heatwave That Hit Highly Vulnerable Population at the End of Ramadan Would Not Have Occurred Without Climate Change,” World Weather Attribution, April 18, 2024, https://www.worldweatherattribution.org/extreme-sahel-heatwave-that-hit-highly-vulnerable-population-at-the-end-of-ramadan-would-not-have-occurred-without-climate-change/.

25“Inventorying Hazards & Disasters Worldwide Since 1988,” International Disaster Database, https://www.emdat.be/.

26“Human Development Report 2023/2024: Breaking the Gridlock,” United Nations Development Programme, 2024, https://hdr.undp.org/system/files/documents/global-report-document/hdr2023-24reporten.pdf.

27“Sahel Human Development Report 2023,” United Nations Development Programme, January 2024, https://www.undp.org/africa/publications/sahel-human-development-report-2023.

28Oli Brown, “Climate-Fragility Risk Brief: North Africa & Sahel,” Climate Security Expert Network, April 2020, https://climate-diplomacy.org/sites/default/files/2021-01/CSEN%20Climate%20Fragility%20Risk%20Brief%20North%20Africa%20Sahel.pdf.

29“Africa’s Constantly Evolving Militant Islamist Threat,” Africa Center for Strategic Studies, August 13, 2024, https://africacenter.org/spotlight/mig-2024-africa-constantly-evolving-militant-islamist-threat/.

30Yousif Elmahdi and Gael Raballand, “Integrity and Transparency of Spending and Security in Sub-Saharan Africa. Are They the Missing Links?,” World Bank Blogs, June 20, 2024, https://blogs.worldbank.org/en/governance/integrity-and-transparency-of-spending-and-security-in-sub-sahar.

31“‘Syria Facing Highest Levels of Humanitarian Need Since Start of 13-Year Crisis’, Senior Official Tells Security Council,” United Nations, June 25, 2024, https://press.un.org/en/2024/sc15744.doc.htm.

32“Syrian Arab Republic: 2024 Humanitarian Needs Overview,” United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, February 2024, https://www.unocha.org/publications/report/syrian-arab-republic/syrian-arab-republic-2024-humanitarian-needs-overview-february-2024-enar.

33Samantha Kuzma, Liz Saccoccia, and Marlena Chertock, “25 Countries, Housing One-Quarter of the Population, Face Extremely High Water Stress,” World Resources Institute, August 2023, https://www.wri.org/insights/highest-water-stressed-countries.

34“Critical Response and Funding Requirements - Response to the Water Crisis in Syria (August 2022),” United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, September 15, 2022, https://www.unocha.org/publications/report/syrian-arab-republic/critical-response-and-funding-requirements-response-water-crisis-syria-august-2022.

35“Democracy Index 2023,” Economist Intelligence Unit, https://www.eiu.com/n/campaigns/democracy-index-2023/.

36Haid Haid, “The Illusion of Legitimacy: Unveiling Syria’s Sham Elections,” Chatham House, July 16, 2024, https://www.chathamhouse.org/2024/07/illusion-legitimacy-unveiling-syrias-sham-elections.

37“Absent Political Progress, Ongoing Violence Putting Syria, Global Community at ‘Terrible Risks’, Special Envoy for Syria Warns Security Council,” United Nations, May 30, 2024, https://press.un.org/en/2024/sc15712.doc.htm.

38“Afghanistan Humanitarian Needs and Response Plan 2024 (December 2023) [EN/Dari/PS],” United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), December 23, 2023, https://www.unocha.org/publications/report/afghanistan/afghanistan-humanitarian-needs-and-response-plan-2024-december-2023.

39“Afghanistan: Socio-Economic Outlook, 2023,” United Nations Development Programme, April 18, 2023, https://www.undp.org/afghanistan/publications/afghanistan-socio-economic-outlook-2023.

40“Approximately 85 Percent of Afghans Live on Less Than One Dollar a Day,” United Nations Development Programme, January 10, 2024, https://www.undp.org/stories/approximately-85-percent-afghans-live-less-one-dollar-day.

41“Emergency Update #9: Pakistan-Afghanistan Returns Response,” Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees Regional Bureau for Asia and Pacific, January 18, 2024, https://data.unhcr.org/es/documents/download/106220.

42“Afghanistan Humanitarian Needs,” OCHA.

43“Whole of Afghanistan Assessment 2023: Provincial Findings Tables,” REACH Initiative, October 2023, https://repository.impact-initiatives.org/document/impact/1cbc1e0d/REACH_AFG_Factsheet_WoAA_2023_Provincial_Findings_Tables_October_2023.pdf.

44“Democracy Index 2023,” EIU.

45“Climate, Peace and Security Fact Sheet: Afghanistan,” Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, February 2023, https://www.sipri.org/sites/default/files/2023-10/23_fs_afghanistan.pdf.

46“Europe’s Contribution to Climate Finance (in €bn),” Council of the European Union, 2024, https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/infographics/climate-finance/; and “Council Conclusions on Climate and Energy Diplomacy,” Council of the European Union, March 9, 2023, https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/62942/st07248-en23.pdf.

47“Global Gateway: EU Partners With South Africa to Invest €280 Million in Its Just and Green Recovery,” European Commission, January 27, 2023, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_23_353.

48Vijaya Ramachandran, “Rich Countries’ Climate Policies Are Colonialism in Green,” Foreign Policy, November 3, 2021, https://foreignpolicy.com/2021/11/03/cop26-climate-colonialism-africa-norway-world-bank-oil-gas/.

49Anchal Vohra, “EU’s Africa Fund ‘Spread Too Thinly’ to Reduce Migration,” Deutsche Welle, September 25, 2024, https://www.dw.com/en/eu-auditors-say-africa-fund-spread-too-thinly-to-reduce-migration/a-70323528.

50“Achievements of the von der Leyen Commission: Stronger Europe in the World,” European Commission, October 2024, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/api/files/attachment/879649/6%20Stronger%20Europe%20in%20the%20world.pdf.

51“European Humanitarian Forum: Commission and Swedish Presidency Set the Goals for EU’s Humanitarian Action,” European Commission, March 21, 2023, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_23_1683; and “European Humanitarian Forum Pledges Over €7.7 Billion for Global Crises,” European Commission, March 19, 2024, https://commission.europa.eu/news/european-humanitarian-forum-pledges-over-eu77-billion-global-crises-2024-03-19_en.

52“Humanitarian Aid,” European Commission European Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid Operations, 2024, https://civil-protection-humanitarian-aid.ec.europa.eu/what/humanitarian-aid_en.

53“The Commission Announces Initial Humanitarian Aid of €1.8 Billion for 2024,” European Commission, February 12, 2024, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_24_678.

54“DAC Recommendation on the Humanitarian-Development-Peace Nexus,” Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2024, https://legalinstruments.oecd.org/public/doc/643/643.en.pdf.

55“Report on the Implementation, Dissemination and Continued Relevance of the DAC Recommendation on the Humanitarian-Development-Peace Nexus,” Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, March 11, 2024, https://one.oecd.org/document/DCD/DAC/INCAF(2023)1/FINAL/en/pdf.

56Vince Chadwick, “Scoop: The EU Aid Cuts Revealed,” Devex, September 26, 2024, https://www.devex.com/news/scoop-the-eu-aid-cuts-revealed-108390.

57“Conflict and Fragility,” Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2024, https://www.oecd.org/en/topics/sub-issues/conflict-and-fragility.html.

58“Development Finance for Climate and Environment-Related Fragility: Cooling the Hotspots,” Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, November 22, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1787/a1bf2a5a-en.

59Joyce Msuya, “Deputy Relief Chief: ‘Imperative’ to Support Resilience, Climate Adaptation Alongside Humanitarian Aid,” United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, December 11, 2023, https://www.unocha.org/news/deputy-relief-chief-imperative-support-resilience-climate-adaptation-alongside-humanitarian.

60“Global Humanitarian Overview 2023: December Update (Snapshot as of 31 December 2023),” January 19, 2024, United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, https://www.unocha.org/publications/report/world/global-humanitarian-overview-2023-december-update-snapshot-31-december-2023.

61“Commissioner Urpilainen and the ECOWAS President Touray Launch a Major Package to Stabilise the Region and Drive West African Socio-Economic Development,” European Commission Directorate General for International Partnerships, October 19, 2023, https://international-partnerships.ec.europa.eu/news-and-events/news/commissioner-urpilainen-and-ecowas-president-touray-launch-major-package-stabilise-region-and-drive-2023-10-19_en.

62Rédaction Africanews and AFP, “Borrell: ‘The EU Has Failed to Strengthen Democracy in the Sahel,’” Africanews, August 13, 2023, https://www.africanews.com/2023/09/13/borrell-the-eu-has-failed-to-strengthen-democracy-in-the-sahel/; and Assitan Diallo and Delina Goxho, “Donor Dilemmas in the Sahel: How the EU Can Better Support Civil Society in Mali and Niger,” Saferworld, March 2023, https://www.saferworld-global.org/resources/publications/1421-donor-dilemmas-in-the-sahel.

63Karen Meijer and Ann-Sophie Böhle, “Climate Change Adaptation in Areas Beyond Government Control: Opportunities and Limitations,” Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, September 2024, https://www.sipri.org/sites/default/files/2024-09/2024_2_adaptation_beyond_gov_control.pdf.

64“Global Conflict Risk Index,” European Commission Disaster Risk Management Knowledge Centre, https://drmkc.jrc.ec.europa.eu/initiatives-services/global-conflict-risk-index#documents/1435/list.

65Ruben Dahm et al., “What Climate? The Different Meaning of Climate Indicators in Violent Conflict Studies,” Climatic Change 176, no. 145 (2023), https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10584-023-03617-x.

66“DAC Recommendation,” OECD.

67“NATO 2022: Strategic Concept,” North Atlantic Treaty Organization, June 29, 2022, https://www.act.nato.int/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/290622-strategic-concept.pdf.