C. Raja Mohan, Darshana M. Baruah

{

"authors": [

"C. Raja Mohan"

],

"type": "legacyinthemedia",

"centerAffiliationAll": "dc",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"Carnegie India"

],

"collections": [],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie India",

"programAffiliation": "SAP",

"programs": [

"South Asia"

],

"projects": [],

"regions": [

"South Asia",

"India"

],

"topics": [

"Foreign Policy",

"Climate Change"

]

}

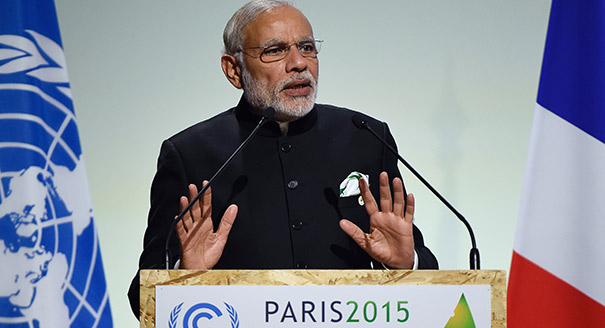

Source: Getty

Raja-Mandala: Modi’s Multilateral Moment

Whatever the outcome in Paris, this round marks an important shift in India’s climate diplomacy.

Source: Indian Express

As he joins world leaders at the Paris conference on climate change this week, Prime Minister Narendra Modi will showcase his effort to develop a new Indian approach to global challenges. Whatever the eventual results from Paris, the current round of climate talks marks an important shift in India’s multilateral diplomacy.

Consider, for example, Modi’s summation of India’s negotiating position on climate change before he headed to Paris: All nations have the responsibility to limit global warming. The emphasis on “all nations” seems to fly in the face of India’s past rigid position on the historic responsibility of the developed nations to bear the immediate burden in mitigating climate change.No, the PM is not giving up on the idea of “common but differentiated responsibility” (CBDR), so central to the Indian discourse on climate change. If India swore by “differentiation” in the past, Modi is now drawing attention to the “common”. Writing in Monday’s edition of the Financial Times, Modi insisted that abandoning the CBDR principle would be “morally wrong”. At the same time, the PM also stressed the importance of a global partnership that does not “put nations on different sides”.

That there’s a fundamental divide between the “Global North” and the “Global South” has long been an article of faith for India’s multilateralism. And nowhere else has this proposition been defined more clearly than the 1992 UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), which divided countries into developed and developing and put the burden of moving towards a low-carbon future on the former. It codified that the North must also provide the finance and transfer technology to assist developing countries in moving towards low-carbon growth alternatives.

As a realist, Modi might have had no problem in recognising that the context that produced the UNFCCC has altered fundamentally over the last two decades. The question of climate change has become a pressing issue — in the international as well as domestic arena. It has also been plain that developed countries have been working hard to break free from the principle of CBDR and other obligations under the UNFCCC. They want emerging economies like China and India to take much more responsibility for mitigating climate change.

If the UNFCCC made the CBDR a holy cow, the governments and Western NGOs have begun to claim that any further use of coal, anywhere in the world, is an unpardonable sin. The purists in New Delhi would have loved to see Modi’s India defend the CBDR to the death against the anti-coal crusaders.

In developing a negotiating strategy for Paris over the last 18 months, Modi has underlined that India’s essential interests — winning time and space for continued coal-use for power generation as it moves towards a new energy mix at home and gaining access to renewable energy technologies — can’t be secured by mere moral posturing. All international negotiations are subject to power politics. Delhi is also aware that for all the talk about the “Global South”, there’s considerable differentiation among the developing countries. China, for example, has cut its own deal with the United States.

Delhi’s leverage and potential for leadership in Paris does not come from posturing; it derives instead from the size of India’s economy and the future impact of its energy choices on global climate. It also comes from the capacity to formulate and promote sensible compromises between competing interests on climate change.

Having changed the tone of India’s official discourse on climate change, signalled Delhi’s commitment to ensuring a productive outcome in Paris and taken a number of steps — as on carbon taxation and setting expansive targets for renewable energy production — Modi has put Delhi in a better position than ever before in the climate negotiations. In a perverse twist, Delhi’s past image as a “spoiler” has given Modi much room to play in Paris as he promises Indian leadership on climate change.

After decades of Indian defensiveness at international forums, Modi is signalling a new strategy that plays hardball on India’s core national interests, demonstrates tactical flexibility, avoids ideological argumentation, builds new coalitions, and contributes to positive outcomes.

Although his many admirers and detractors might not like the comparison, Modi is returning India to the Nehruvian conception of international leadership.

In the early years after Independence, Delhi was not bogged down by the idea of leading the “Global South” in a perennial confrontation with the North. Nehru saw India as one of the few natural leaders of the international system capable of setting the global agenda, from human rights to nuclear-testing. He matched that vision with practical steps that promoted synergy between the national and the international. India today has much larger economic heft to influence global outcomes. The current effort in Paris to bring India’s multilateral diplomacy in line with its new weight in the international system has been long overdue.

About the Author

Former Nonresident Senior Fellow, Carnegie India

A leading analyst of India’s foreign policy, Mohan is also an expert on South Asian security, great-power relations in Asia, and arms control.

- Deepening the India-France Maritime PartnershipArticle

- Shanghai Cooperation Organization at Crossroads: Views From Moscow, Beijing and New DelhiCommentary

- +1

Alexander Gabuev, Paul Haenle, C. Raja Mohan, …

Recent Work

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

More Work from Carnegie Europe

- Europe on Iran: Gone with the WindCommentary

Europe’s reaction to the war in Iran has been disunited and meek, a far cry from its previously leading role in diplomacy with Tehran. To avoid being condemned to the sidelines while escalation continues, Brussels needs to stand up for international law.

Pierre Vimont

- Taking the Pulse: Can European Defense Survive the Death of FCAS?Commentary

France and Germany’s failure to agree on the Future Combat Air System (FCAS) raises questions about European defense. Amid industrial rivalries and competing strategic cultures, what does the future of European military industrial projects look like?

Rym Momtaz, ed.

- Macron Makes France a Great Middle PowerCommentary

France has stopped clinging to notions of being a great power and is embracing the middle power moment. But Emmanuel Macron has his work cut out if he is to secure his country’s global standing before his term in office ends.

Rym Momtaz

- How Can Europe Renew a Stalled Enlargement Process?Commentary

Despite offering security benefits to candidates and the EU alike, the enlargement agenda appears stalled. Why is progress not being made, and is it time for Europe to rethink its approach?

Sylvie Goulard, Gerald Knaus

- How Turkey Can Help the Economies of the South Caucasus to DiversifyArticle

Over the past two decades, regional collaboration in the South Caucasus has intensified. Turkey and the EU should establish a cooperation framework to accelerate economic development and diversification.

Feride İnan, Güven Sak, Berat Yücel