Michael Pettis

{

"authors": [

"Michael Pettis"

],

"type": "commentary",

"centerAffiliationAll": "",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"Carnegie China"

],

"collections": [

"Carnegie China Commentaries"

],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie China",

"programAffiliation": "",

"programs": [],

"projects": [

"China’s Reform Imperative"

],

"regions": [

"China"

],

"topics": [

"Economy"

]

}

Source: Getty

Why Should China Borrow Abroad?

In spite of China’s extraordinarily high investment levels, domestic savings nonetheless exceed domestic investment by quite a lot, making it a large net exporter of capital.

This publication is a product of Carnegie China. For more work by Carnegie China, click here.

An article in Xinhua on July 23 says that the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) will actively support high-quality enterprises of various ownership structures in borrowing foreign debt. According to the article:

China is set to support prominent, creditworthy companies that promote high-quality development within the real economy by allowing them to borrow medium to long-term foreign debt. The NDRC announced this initiative Tuesday as part of the country’s strategy to further open up and enhance cross-border financing facilitation.

This strikes me as a little curious. In spite of China’s extraordinarily high investment levels, domestic savings nonetheless exceed domestic investment by quite a lot, making it a large net exporter of capital. We can see this in the huge trade surpluses the country has been running. It is worth noting that China’s current account surpluses are much lower, but there are real questions about the extent to which net outflows that belong in its capital account have shown up in the current account. Council on Foreign Relations’s Brad Setser has written extensively about this, including here and here.

Either way, this implies that China doesn’t suffer from a domestic capital shortage. Add in the fact that Chinese interest rates are much lower than U.S. (and other) interest rates, and that the US dollar (USD) has been volatile relative to the renminbi (RMB), and it’s hard to see why the regulators would want to encourage Chinese companies to borrow abroad—almost all of which is likely to be in foreign currencies.

One reason may be because the People’s Bank of China (PBoC) wants to expand its domestic money supply without putting downward currency pressure on the RMB. If Chinese companies borrow USD to convert into RMB, they create demand for RMB. As they sell the USD that they acquired through borrowing to the PBoC, whose reserves subsequently rise, the PBoC creates additional RMB as it purchases the USD. I believe this has the effect of expanding to domestic money supply without putting downward pressure on the exchange value of the RMB, something the PBoC has tried to avoid—probably because it worsens trade relationships and because it tends to increase capital flight. If that is the case, it might explain why a country that exports capital wants nonetheless to encourage its large companies to borrow abroad.

For those who worry about the risk of an external debt problem, there isn’t much cause for concern. By the end of 2023, China’s total outstanding foreign debt stood at $2.45 trillion, with medium- to long-term debt accounting for 44 percent, according to the State Administration of Foreign Exchange. Against that, the PBoC has over $3.2 trillion in reported reserves, and there are another roughly $2 trillion held by other state-controlled financial entities. China has more than enough foreign currency to manage external debt risks quite easily.

About the Author

Nonresident Senior Fellow, Carnegie China

Michael Pettis is a nonresident senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. An expert on China’s economy, Pettis is professor of finance at Peking University’s Guanghua School of Management, where he specializes in Chinese financial markets.

- What’s New about Involution?Commentary

- Using China’s Central Government Balance Sheet to “Clean up” Local Government Debt Is a Bad IdeaCommentary

Michael Pettis

Recent Work

More Work from Carnegie Europe

- Resetting Cyber Relations with the United StatesArticle

For years, the United States anchored global cyber diplomacy. As Washington rethinks its leadership role, the launch of the UN’s Cyber Global Mechanism may test how allies adjust their engagement.

Patryk Pawlak, Chris Painter

- How Europe Can Survive the AI Labor TransitionCommentary

Integrating AI into the workplace will increase job insecurity, fundamentally reshaping labor markets. To anticipate and manage this transition, the EU must build public trust, provide training infrastructures, and establish social protections.

Amanda Coakley

- Taking the Pulse: Can the EU Attract Foreign Investment and Reduce Dependencies?Commentary

EU member states clash over how to boost the union’s competitiveness: Some want to favor European industries in public procurement, while others worry this could deter foreign investment. So, can the EU simultaneously attract global capital and reduce dependencies?

Rym Momtaz, ed.

- Europe Falls Behind in the South Caucasus Connectivity RaceCommentary

The EU lacks leadership and strategic planning in the South Caucasus, while the United States is leading the charge. To secure its geopolitical interests, Brussels must invest in new connectivity for the region.

Zaur Shiriyev

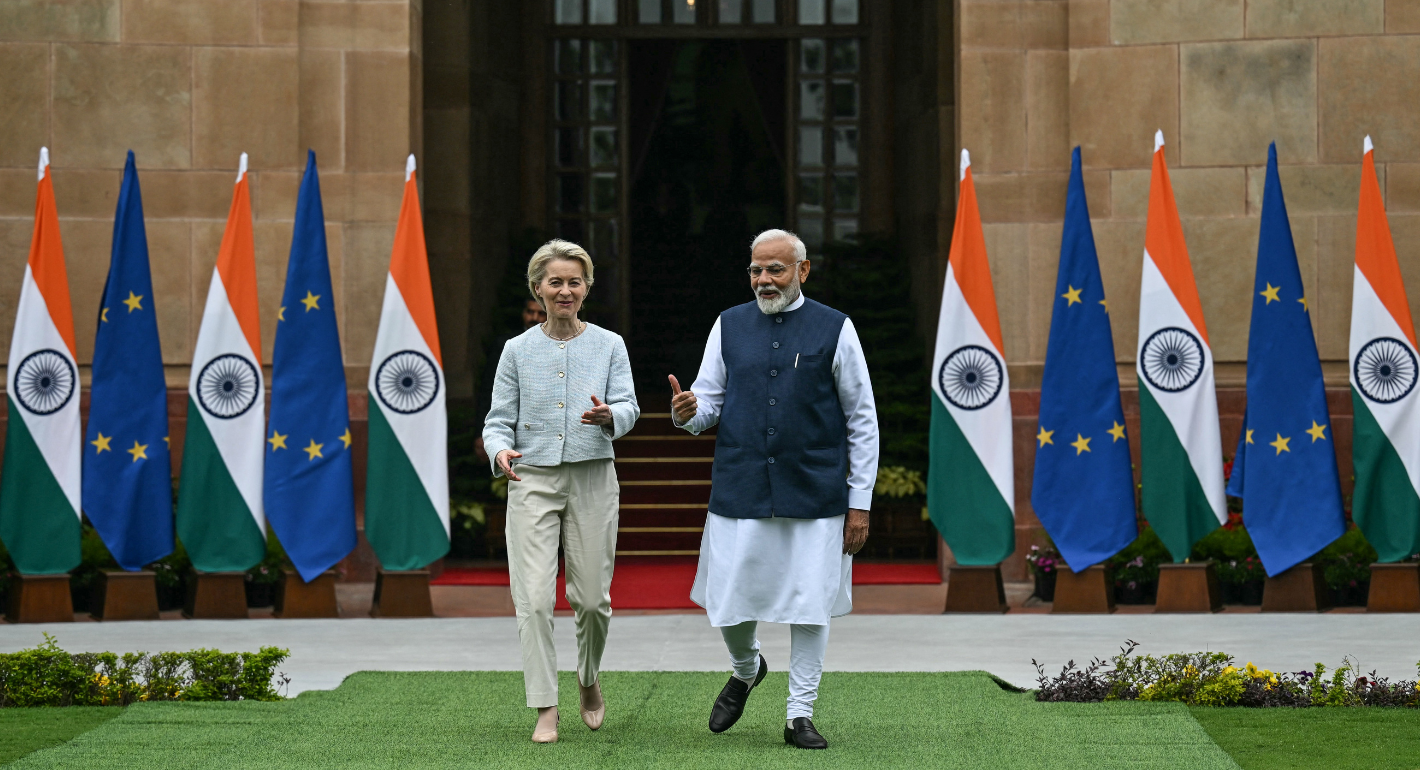

- The EU and India in TandemCommentary

As European leadership prepares for the sixteenth EU-India Summit, both sides must reckon with trade-offs in order to secure a mutually beneficial Free Trade Agreement.

Dinakar Peri